Going into the new school year, Chicago Public Schools dramatically simplified school choice in the city by creating a unified high school enrollment system. Rather than submitting multiple applications to multiple district-run choice programs and charter schools with multiple deadlines and acceptance timelines, families were able to rank their preferred public school options in one place and await an offer from a school that had space for their child and aligned with their preferences.

Studies from other cities, like Denver, have shown that unified enrollment systems like Chicago’s can reduce “grey markets” for schooling, which favor families who understand how to navigate bureaucracy or have the time to apply to multiple schools. They can also help shine a light on the areas of a city where families simply need access to better schools.

In that vein, the University of Chicago’s Consortium on School Research recently released an analysis showing that more than half of families who participated in the new system received an offer at their first-choice public high school. Four out of five families received an offer at one of their first three choices. For those who believe in parental choice and the idea that “fit” between families and schools matters, these numbers look like good news. They suggest most families are getting into the schools they want—even under an enrollment system that is less prone to gaming and more user-friendly for parents.

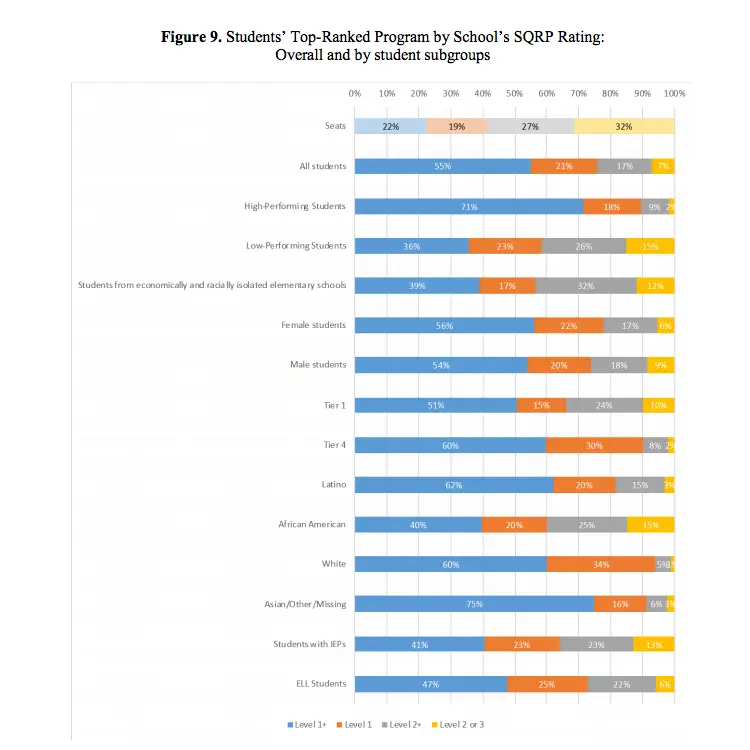

But these encouraging numbers might also point to tougher questions about school improvement. As Jason Weeby has noted, while Chicago families seemed to prefer higher-performing schools over lower-performing ones, students from economically disadvantaged backgrounds and schools that were already racially or economically isolated were less likely to rank higher-performing schools among their preferred enrollment options, and more likely to select lower-performing ones. Research suggests families value school performance, but other factors, like travel distance or a lack of good information on school quality, can affect their ability to act on that preference. In other cities with unified enrollment systems, including Denver, New Orleans, New York City, and Washington D.C., families with lower household incomes or lower parental education levels report more constraints in their search for high-performing schools and more difficulty finding transportation to and from school. (The Chicago researchers say they plan to explore other issues, including the geographic factors that affect parent choices in the Windy City, in future reports.)

So while the initial results of Chicago’s move to unified enrollment suggest most families are getting access to the schools they want, some may still be getting the ones they’re forced to settle for.

Disadvantaged students, including those with low test scores, were less likely than their peers to rank schools with the highest performance scores as their top choices.

Source: University of Chicago Consortium on School Research.

High match rates between families and schools may not be the best indicator of how well choice is working in a city. In New Orleans match rates have fallen over time. Going into the 2014-2015 school year, 77.7 percent of families received one of their top three choices. In an analysis released in August by Louisiana state auditors, that percentage fell to 65.5 percent for the current school year. But auditors said that was likely due, in part, to the fact that families got access to more elite, high-demand schools through the citywide enrollment system, known as OneApp. Match rates remain high in Cleveland, but that may not last as information and outreach campaigns have encouraged more families to apply to high-performing schools. More concentrated demand for high-performing schools in Cleveland may reflect a better choice environment—but may also cause match rates to fall. Cities like Denver have seen declines in match rates for their high schools, and officials have acknowledged there still aren’t enough spaces in high-quality schools for students who want them.

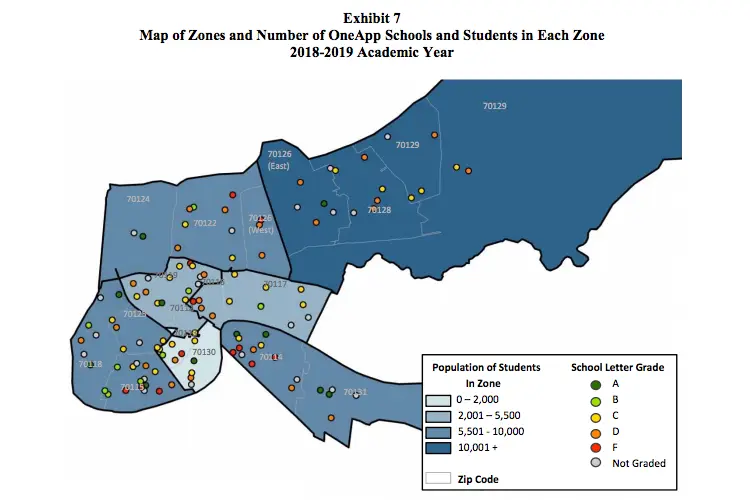

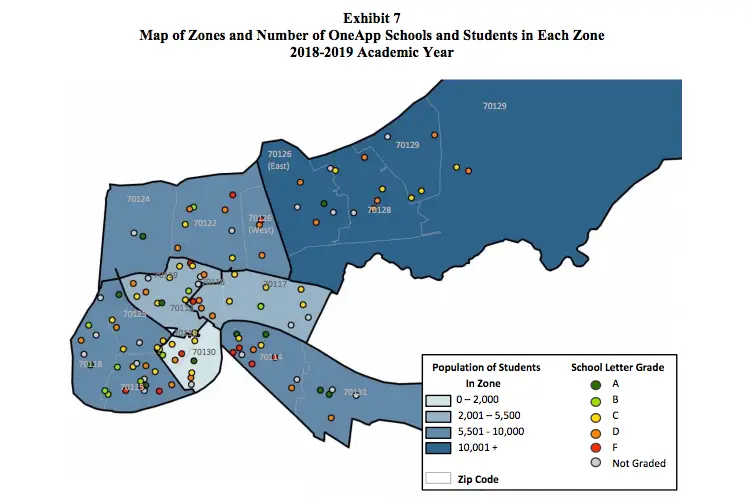

Match rates like those reported in Chicago also don’t show how the choosing experience differs for students across a city. In New Orleans, the new state audit reveals some tradeoffs families must navigate. The enrollment system gives students priority in school admissions if they attend the school in the geographic zone where they live. More than half of families in the city enroll in schools outside their zone. But less than one-third of families living on the Westbank, across the Mississippi River from the rest of the city, attend schools outside their zone. The difficulty of cross-river commuting may limit the choices that are truly feasible for these families.

The Westbank zone (see bottom right area of the map below) is home to four top-rated public schools, including Edna Karr High School, which was one of the highest-rated and most highly sought schools in the city. But it’s also home to four schools rated F and another three rated D. To improve school options for families living in the area, it might make sense to focus on improving the lower-performing schools, or working out arrangements with neighboring Jefferson Parish to allow more families to take advantage of its public schools. Last year, our analysis of outlying Denver neighborhoods reached similar conclusions.

New Orleans offers some families geographic preference in its all-choice school system.

Source: “Analysis of Student Placement: Unified Enrollment System (OneApp),” Louisiana Legislative Auditor, August 2018.

Unified enrollment is not a panacea for educational ecosystems in cities. But the new system in Chicago may provide useful insights into the constraints families face, and help school system leaders identify areas in the city where they need to prioritize school improvement efforts—like replicating sought-after programs, creating new ones, or intensifying efforts to improve existing schools. For Chicago Public Schools, persistent enrollment declines may make those changes all the more difficult to achieve. The school system already has 13,000 more seats than students to fill them. That means it may have to find ways to provide new and better programs while, at the same time, reducing the number of programs overall.

New tools highlight an enduring truth: Families want high-quality schools that are safe, close to home, and easy to get to. Making that a reality for all families is still the goal—and still the hard part.

Travis Pillow is a writer, editor, and former journalist with deep knowledge of the national education reform landscape. He is working with CRPE to provide editorial and communication strategy support. Betheny Gross is research director at CRPE.