Whether or not schools open should be determined by scientific guidelines, not politics. But is it?

The research team at CRPE has been tracking and reporting on district reopening plans. In early August, my colleagues reported the striking findings from our representative sample of nearly 500 U.S. school districts. They found that while most urban districts were planning to open online, most rural districts were planning to open in-person. Suburban districts were fairly evenly split between online, in-person, and hybrid plans (where some smaller portion of students attend on a given day). At the time of that analysis, nearly a third of districts had not yet announced their intentions.

My colleagues just completed an update to their analysis. The big news is that nearly all districts have now announced how they will open, but the basic trends we identified in our last analysis still hold. Urban districts are still far more likely to go virtual than are rural districts.

We were curious, however, whether the different approaches were directly tied to local health conditions, or if other factors were at play.

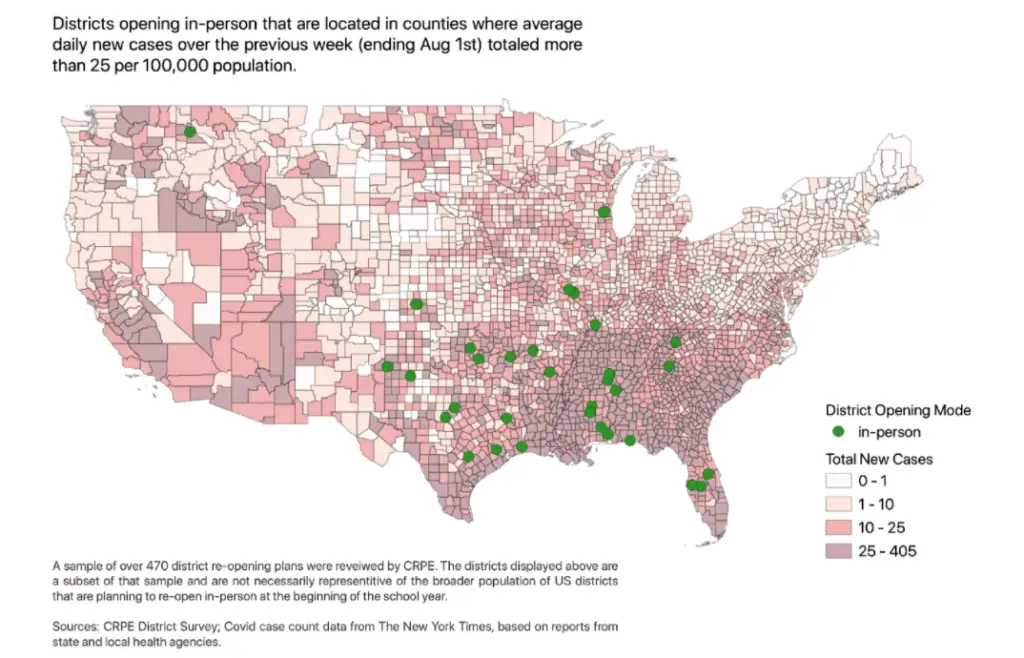

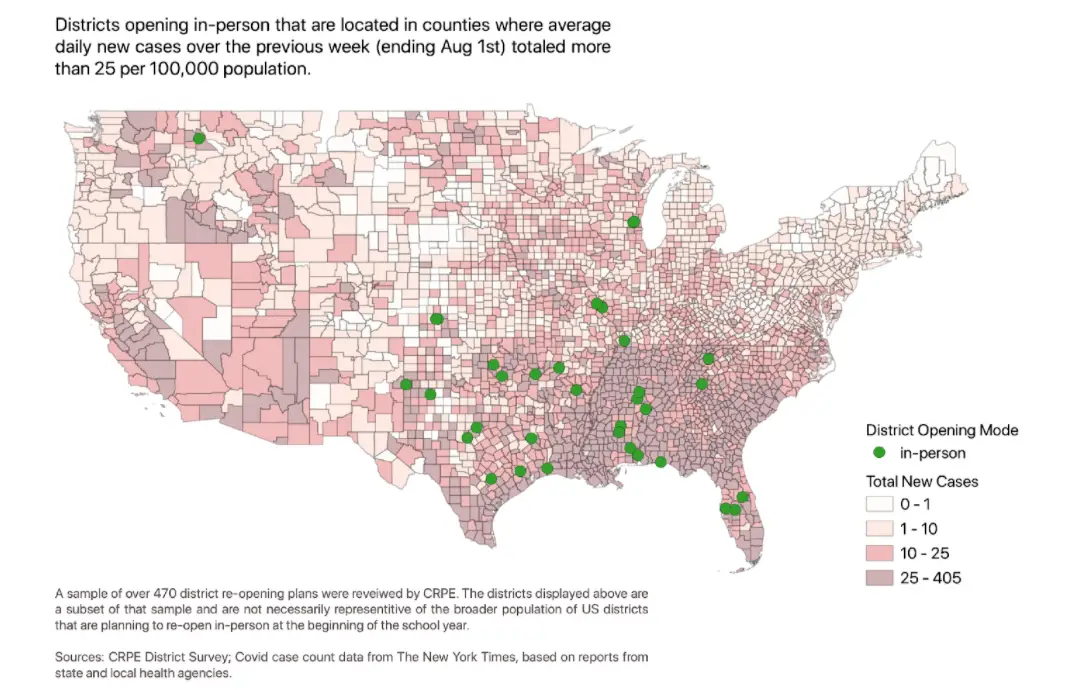

The map below shows districts in our sample that plan to reopen in person despite being in a county that falls into the Harvard Global Health Institute (HGHI) “red” category, where in-person school reopening is not advised. Seven percent of the 477 districts we sampled fell into this category. In other words, they are opening when they probably should not. It’s clear from the map below that these “ill-advised” districts are primarily in the Southeast—in states like Florida, Georgia, and Texas.

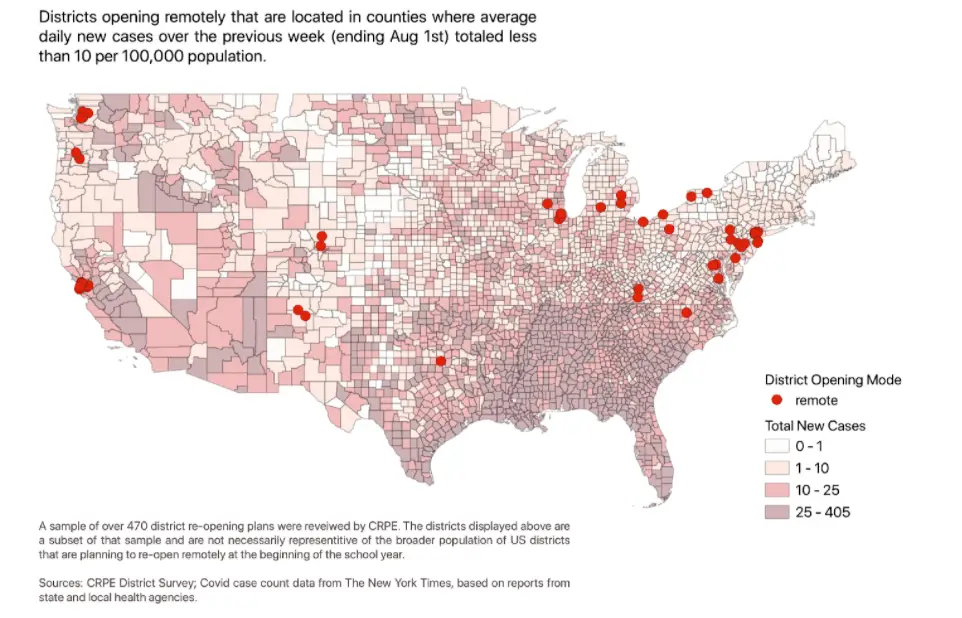

We also wanted to know whether the opposite was true: Are some districts being too cautious about reopening—going fully virtual when the science says it may be relatively safe to bring at least some students back in person? This next map shows the answer is yes. Eight percent of the districts in our sample are going virtual-only in a county HGHI would deem “yellow,” where schools are advised they can open in-person to at least some students. In other words, they could probably open under hybrid models, but are choosing not to. Notably, these “cautious” districts are much more likely to be located in coastal states with stronger teachers unions.

So a nontrivial portion of the districts we analyzed seem to be opening in-person in ill-advised conditions. That seems like an obvious problem. But there are also a fair number of districts going fully virtual when they may not need to. Also a problem.

Just eyeing the location of the districts suggests politics are coming into play here, and our analysis supports this conclusion. In our sampling of districts, if you are a student in a district with an “ill-advised” opening, you are 72 times more likely to live in a state with a Republican governor than in a state with a Democratic governor. A student in a “cautious” district is 27 more times likely to be in a state with a Democratic governor.

These results are consistent with other recent research showing how school reopening plans are often driven by politics. The categories of districts we map here are not necessarily representative of the broader population. Our sample was designed to statistically represent the nation’s school districts as a whole, not to tease out fine-grained differences. But they do suggest that, in many districts, reopening plans are not consistent with scientific guidance and that the approaches to reopening are being influenced by political forces on both the right and the left.

The last place politics belong is in the classroom, especially during a pandemic. Opening in-person against the advice of health officials puts students, teachers, and all those they come in contact with at risk. However, staying closed despite low-risk conditions unnecessarily inhibits in-person learning, socialization, and support for students who need it most. Keeping schools closed requires parents and guardians to stay home with children or pay for child care in order to go to work.

State and federal leaders must urgently issue clear and objective guidance to ensure school reopenings follow the science of the virus, not the politics of the moment.

*

Note on methodology:

An August 14, 2020, New York Times opinion article, “Is Your Child’s School Ready to Reopen?” by Yaryna Serkez and Stuart A. Thompson, made use of school reopening guidelines developed by the Harvard Global Health Institute.

The guidelines characterize COVID-19 risk levels in terms of daily new cases per 100,000 people. Based on this guidance level, “Red” with >25 daily new cases per 100,000 people should be associated with general stay-at-home orders. Levels “Orange” (10-25 daily new cases) and “Yellow” (1-10 daily new cases) allow prioritized in-person reopening of schools as local capacity to do so permits. Level “Green” (less than 1 daily new case) is a condition where all schools could be open in-person to all students. The guidance recognizes that low testing rates can mask local outbreaks and recommends using new death trends as a supplement to new case counts.

The Times opinion piece used estimates of testing rates, often statewide rates when county estimates were not available, as a supplemental measure. We instead looked at new death trends at the county level to identify where outbreaks might not be adequately represented by the daily new case counts. In none of the counties with low daily new case counts where our sample of districts are located were new death trends high enough to suggest that undercounting of cases was a significant problem.