A lot has been asked of American students this spring. They have been away from their friends and at the mercy of schools unprepared to educate them from a distance. We wanted to know more than anecdotes about the student experience and what they say they need and want going into the fall. We reviewed all available national- and state-level surveys and looked for common themes and important data points.

Students have rarely been asked their views on education in the time of COVID-19, especially compared to teachers and parents. We looked at 76 surveys of views on education during the pandemic, but found only 7 national student surveys at the K–12 level, and only 4 draw from representative samples (see table below).

Here are the major themes:

Most students say they experienced very little meaningful online instruction.

Although the vast majority of students say they had access to some form of online education this fall, a nationally representative survey by the Center for Promise at America’s Promise Alliance showed that 78 percent of teens surveyed report spending between one and four hours on online learning during a typical day—far less time than a regular school day. Thirty-two percent of all students surveyed say they had two or less hours of online learning per day. Even taking into account that a typical school day includes time for socializing, transferring between classes, etc., this is a concerning loss of learning time.

According to one national survey by Common Sense Media, nearly one in four teens say they’re connecting with their teachers less than once a week. Almost half (41 percent) haven’t attended an online or virtual class since in-person school was canceled.

For most students, then, remote learning this fall was typically a solo endeavor: watching a teacher’s pre-recorded video, doing a project assigned by email, or even completing worksheets mailed home. Only a small number of students are regularly connecting online with teachers and classmates. Even then, students spent far less time than usual learning anything.

Most students are not happy with online classes and are concerned about long-term impacts.

Given that the vast majority of students experienced the least engaging version of remote learning (without engaging with classmates and teachers), it’s no wonder students express dissatisfaction with it.

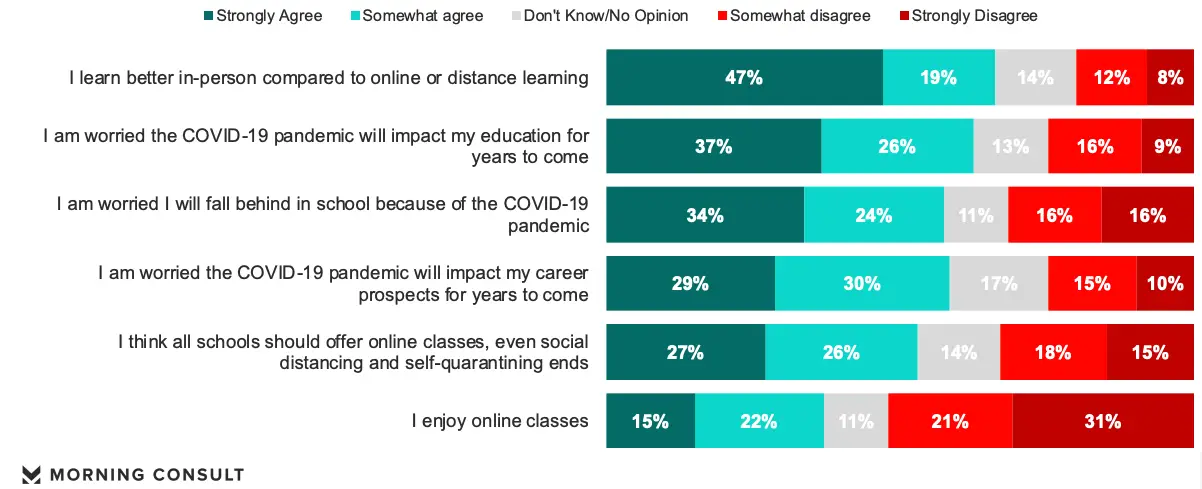

In the few nationally representative queries of student perceptions of online learning, most students say they strongly prefer in-person classes. In one national student survey by Morning Consult, the majority (66 percent) say they strongly or somewhat agree that they “learn better in-person compared to online or distance learning.” Only 37 percent of respondents strongly or somewhat agree that they “enjoy online classes.”

Thinking about your experience as a student during COVID-19, also known as coronavirus, do you agree or disagree with the following statements?

Source: Morning Consult survey.

Students surveyed by Morning Consult say they are worried about the long-term impacts of having missed school this spring. Over 60 percent of high school students strongly or somewhat agree that the pandemic will have a long-term impact on their education for years to come, while nearly 60 percent feel the same way about their career prospects.

In a survey by YouthTruth, only half of students say that while schools were closed their teachers gave them assignments that really helped them learn, and just 39 percent say they learned a lot every day. Concerningly, students who previously had poor grades in school were much less likely to report learning a lot every day, raising the possibility that students who struggled before may struggle even more during COVID-19.

It’s notable, however, that some students—while in the minority—seem to enjoy and even prefer the online environment. Most agree that online classes should be an option even after social distancing ends. In the YouthTruth survey, students say that while distractions, lack of motivation, and lack of social connections were challenging aspects of remote learning, they like some things. In particular, students report they enjoy getting project-oriented assignments, being able to work at their own pace, and spending more time with family.

As we look to spring, it will be important to understand why that is the case. And yet, only one national (but not representative) survey by PDK International asked students what they do or do not like about remote learning—for example, what kinds of lessons keep them engaged and on track. What they learned was enlightening. While 76 percent express a desire for their school to help them maintain a routine schedule and sense of structure, only 23 percent say their school has done this effectively. Only 32 percent say their school has done a good job of keeping them informed about important schoolwide decisions, policy changes, and other basic information related to the pandemic.

Students have starkly different remote learning experiences.

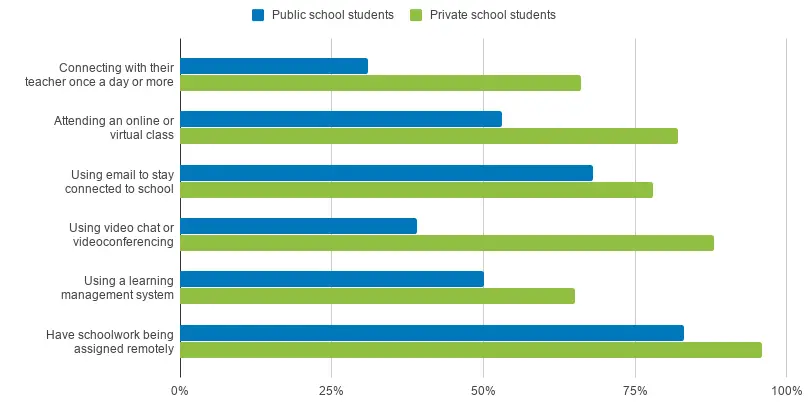

Some students have had a far better online learning experience than others. According to the same Common Sense Media survey, twice as many private school teens (66 percent as compared to 31 percent) say they are connecting with their teachers once a day or more. And twice as many (88 percent compared to 39 percent) say they are using video chat or video conferencing.

Percent of teens who report doing each of the following while in-person school activities are canceled

Source: Common Sense Media teen survey.

Shockingly little information is available about how public school students from different backgrounds experience online education, or the experiences of students from charter vs. district schools. This will be important to assess in future surveys as research shows public school districts have taken very different approaches.

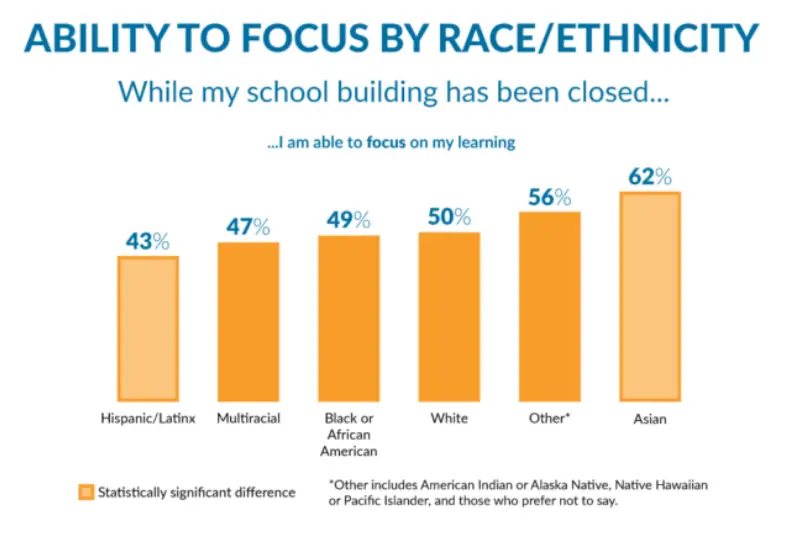

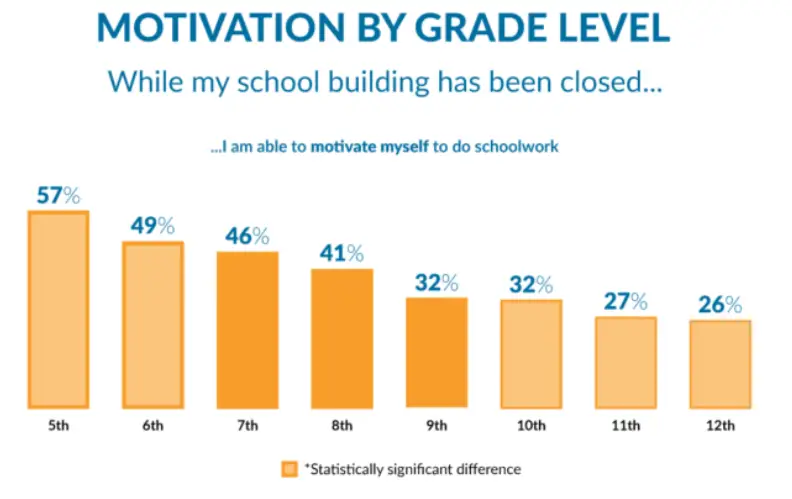

Across a few surveys, students report they struggled with engagement and connection while schools were closed. According to YouthTruth, only 50 percent of students say they were able to focus on learning and only 41 percent said they were motivated to do schoolwork. These responses varied significantly by race and by grade level.

Source: YouthTruth Students Weigh In.

Source: YouthTruth Students Weigh In.

Common Sense Media’s survey—the only disaggregated results we’re aware of—did show meaningful differences across student populations when it comes to feelings of disconnection during COVID-19. Asian students are more likely to feel disconnected from their school communities than white, Black, and Latinx students; Latinx students report feeling less connected to both school adults and peers than either white or Black students. Students in rural communities report feeling less connected to their school communities than students in cities, towns, or suburbs.

It will be very important to learn whether live instruction and more structured learning time help students feel more connected while quarantined. We know, for example, that rural students are less likely to have stable wifi connections and device access. Does this lack of access exacerbate depression and anxiety? If so, that should call for urgent federal action to ensure connectivity for all students.

Students experience heightened anxiety and depression.

There has been widespread speculation that students are experiencing significant challenges from continued social isolation. National surveys of students confirm that.

According to data from the Center for Promise’s survey, more than one in four young people reported an increase in losing sleep because of worry, feeling unhappy or depressed, feeling constantly under strain, or experiencing a loss of confidence in themselves.

Increased loneliness is reported among 42 percent of teens surveyed by Common Sense Media, with a higher portion of girls (49 percent) stating this. YouthTruth’s survey shows an even larger gender divide. When asked whether anxiety, depression, or stress make it hard to do online assignments, 38 percent of boys responded “yes” compared to 57 percent of girls—and an alarming 70 percent of students who identify as neither.

In a survey focused on students of color conducted by Our Turn, 65 percent of students surveyed state that their mental health has worsened during this pandemic, and 28 percent state that their physical health has also worsened during this time. More than half (56 percent) are concerned about their mental health in both the short- and long-term.

A smaller portion of students in the Our Turn survey say they or their family are experiencing financial (38 percent), housing (9 percent), and food insecurity (11 percent). More than a third (37 percent) cite challenges from additional responsibilities that they have had to take on at home.

Anxiety is high. In the Morning Consult survey, half of student respondents strongly or somewhat agree that they’re “worried about the current job market and are more likely to accept a role even if it does not fit exactly what they want.”

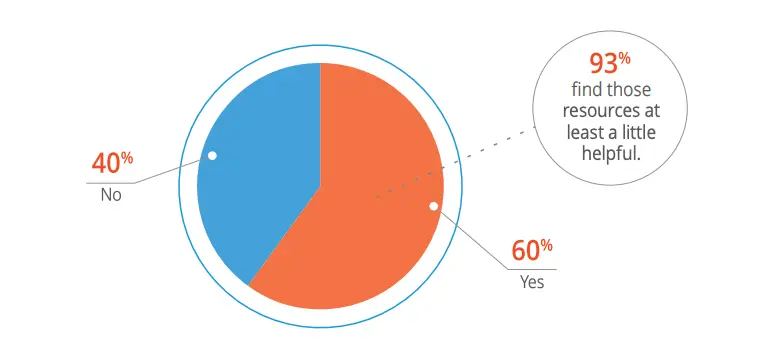

Despite the mounting evidence that students are experiencing what the Center for Promise deemed “a collective trauma,” students say they are receiving little support. A full 40 percent say they have not been offered social or emotional support by an adult from their school. Those that have say they are at least a little helpful.

Percent of youth offered social or emotional support by an adult from their school

Source: Center for Promise: The State of Young People during COVID-19

Given the pain and anxiety students are expressing, it will be critical this fall to offer all students supports that are, hopefully, more than just “a little” helpful. Research-based supports and interventions are available and many can be delivered virtually. It also may be the case that better connections to classmates via live instruction and structured learning help. There is no excuse for continuing to ignore what students are so clearly telling us.

Students have opinions about how they want remote learning to work, but few are asking them.

Few surveys have asked students if and how they want schools to reopen next year, and according to the Our Turn survey, three of four (76 percent) of students surveyed say they were not consulted prior to their school or campus closing in the spring.

This is a shame. What’s clear from surveys of teens, at least, is that they hold strong views about online learning. Despite their clear disdain for the type of online learning they are getting now, students in existing national surveys are not shy to give their opinions—negative and positive—about online learning. Young people like some things about this disruption in their normal schooling. The majority of teens, according to the Morning Consult survey, say they have a new appreciation for having time to pursue hobbies, having close friends, and making money.

As fall nears, most school districts are surveying parents about their preferences for reopening. Some are also asking students. The Muscogee County School District in Georgia asked students about their preferences for reopening and also asked them about their experience in the spring. The results showed that Muscogee students who responded were split evenly between those who want to come back full time in person and those who want a partially virtual/partially in-person option (36 percent and 43 percent respectively). The results also revealed that most students said they adjusted pretty well to online learning, but many said they had trouble adjusting.

In Nebraska, Omaha Public Schools asked students of all ages to respond to a series of questions ranging from their feelings about the pandemic to comfort levels with various return to school scenarios, including mask-wearing. The responses were revealing. Students of all ages reported feeling anxious and sad. High school students reported feeling bored and often hopeless. Omaha officials also asked what would be most important to students if remote learning had to continue. Students overwhelmingly asked for assignments that could be completed at their own pace, but they also wanted live instruction, time to socialize with friends, and frequent feedback on progress.

Student views should count.

Students hold strong views about remote learning and have the most to lose if it doesn’t go well. We owe it to them to ask more about their experiences. We can learn something from the limited national student surveys, but more information is needed. It’s critical to assess what kinds of remote learning students most enjoy and feel engaged with, and to understand the connection between mental wellness and school activities and interventions. We also need to know much more about how students with unique needs, like students with disabilities and English language learners, struggle or excel when learning at a distance.

Finally, as schools prepare to reopen this fall, we will need to learn how students fare over the next year so schools and school systems can adapt quickly to what works or doesn’t work for them.

CRPE’s Evidence Project, in partnership with the PIE Network, will continue to track and report on these and other survey findings as they come in. Our website has a running list of pandemic-related education polls and surveys, as well as syntheses of other education research findings related to COVID-19.

Hannah Oakley, a policy analyst for the PIE Network, and Alvin Makori, a research assistant at CRPE, contributed to this analysis of student surveys.