The State of the American Student: Fall 2022

A guide to pandemic recovery and reinvention

This report draws on data the Center on Reinventing Public Education (CRPE) has collected and synthesized over the course of the pandemic. It outlines the contours of the crisis American students faced during the Covid-19 pandemic and begins to chart a path to recovery and reinvention for all students—which includes the essential work of building a new and better approach to public education that ensures an educational crisis of this magnitude cannot happen again. This is the first in a series of annual reports CRPE will produce on pandemic recovery and renewal.

“Diverse needs will require diverse solutions, delivered by a diverse cast of community actors far beyond the bounds of our current public education system.”

Robin Lake, Director of the Center on Reinventing Public Education

Fast facts

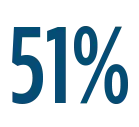

Percentage of parents of students with cognitive disabilities who reported schools abandoned their child’s legal right to access an equitable education when they moved to remote learning

Source: Understood

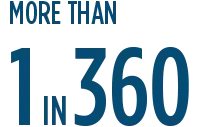

Number of children

estimated to have lost

a parent or caregiver

during the pandemic

Source: COVID Collaborative

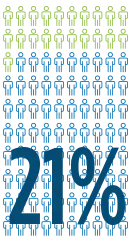

Percentage by which income-based gaps in elementary math achievement widened during the pandemic

Source: Annenberg Brown University

Percentage of teachers who reported covering all, or nearly all, the curriculum they would cover in a typical year during the 2020–21 school year

Source: RAND Corporation

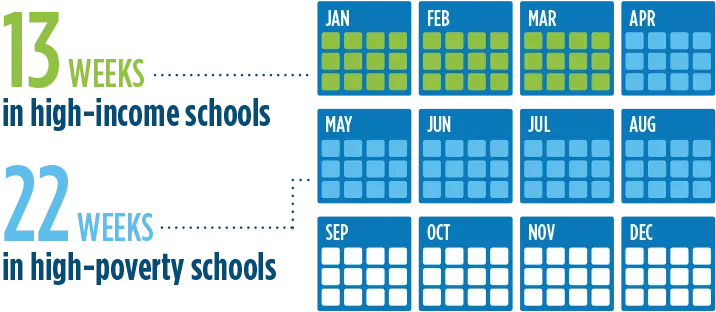

Lost academic instruction in schools operating fully remotely in 2020-21

Source: Harvard University

Student Voices

We asked students about their pandemic learning experiences and what they need now from schools to be successful.

Mia Moore

Age: 16

Mecca Patterson-Guirdy

Age: 17

Miles Lorenzo

Age: 10

Liv Birnstad

Age: 17

Charlecia Brown

Age: 16

Levi Griffith

Age: 16

Kesar Gaba

Age: 18

Levi Griffith: Hanover, KS

Liv Birnstad: Washington, D.C.

Mia Moore: Milwaukee, WI

Students from around the country spoke with CRPE in spring and summer 2022 to discuss what they and their peers need from schools to successfully recover from the pandemic. Many asked for more mental-health resources, more counselors, more project-based learning, more time for developing social connections, and more attention paid to the dynamics of race and racial identity in school.

Key findings

- The vast majority of K-12 students have suffered significant learning losses of half a year or greater. With few exceptions, losses are greater in mathematics than in reading.

- Learning losses were smaller in 2021-22, when more schools were open, than in 2020-21. But substantial numbers of students have continued falling further behind normal levels of learning for their age and grade.

- Students with disabilities have suffered disproportionate academic impact. But few studies have examined the disparities in outcomes for different subpopulations of students with disabilities.

- The pandemic caused widespread harm to students’ mental health and social and emotional well-being.

- Before the pandemic, America had the largest academic performance gap between rich and poor students in the industrialized world, according to international PISA scores.

- Rising suicides among youth and soaring mental-health challenges—especially among girls—were on the rise before the pandemic. Students grew more bored and more disengaged the longer they progressed through school, surveys showed.

- From February 2020 onward, wildly varied responses from school systems meant every student had a different pandemic education experience.

- In the void left by school closures, students found new space to explore their interests, affirm their identities, or tailor learning experiences to their needs.

- School closures also prompted some families to construct learning environments all their own—either to supplement the remote learning they received from their schools or to replace their schools with something new and different.

- Anecdotal reports abound about how students with learning differences, disabilities, and other complex needs benefited from opportunities to adjust the pace of their learning, participate in virtual classes free from stigma, or collaborate with teachers in ways that would not have been possible in a traditional classroom.

- While the disruptions to schooling hurt many students, they also upended the norms of a system that, too often, had failed to serve these students well. The disruptions created opportunities to experiment with new approaches.

Roadmap to recovery

The urgency and complexity of this situation require an ambitious long-term recovery plan that ensures every student gets what they need before they graduate, no matter what. That will require big, creative plans, not little ones; clear metrics for defining success; serious metrics for tracking progress; and deep investment in testing and scaling innovations.

- Teachers, parents, and other potential community “helpers” need to be informed about each child’s specific needs and progress so they can coordinate individualized solutions.

- Every student and their family should have a full account of what they are owed, what it will take to meet their future aspirations, and how their education system will deliver it.

- Every student should have access to a diverse array of resources, programs, and schools to meet their unique needs.

- The federal government, philanthropists, and other organizations can help rally states to the cause and communities to come together to set postpandemic priorities for their local education systems.

- All 50 states should track and transparently report on progress toward restitution and recovery. This reporting should not be focused on test scores alone.

- Our education system should support diverse teams of educators who collaborate in and outside of school to design rich learning experiences, deliver tutoring and extra support to students who need it, and give students space to take risks and explore their interests.

- We need a national research and development effort that identifies promising initiatives, rigorously tests their efficacy, reports results to policy makers and philanthropists, and identifies other systemic gaps that further innovations should address.

What we do next matters

In the future, we could look back on this time as the turning point. In five years, an updated version of this report could read as follows:

In fall 2022, things looked bleak. Adults were coming to grips with mounting mental-health and academic crises facing the nation’s students. New waves of disruptions continued to hamper the nation’s schools as they struggled to stay open, hire enough staff, and sustain something approximating normal operations.

That was the moment when leaders in government, business, faith communities, and civic organizations realized a return to normal would not be possible. A new coalition rallied with parents and educators to invest in a massive retooling. It took some time, but in the end, we pushed through old barriers and built a public education system of which we could all be proud.

The community became a source of expertise and support for students. Therapists, counselors, and social workers designed programs to help students reconnect with their friends and recover from the trauma of the pandemic. Students of color had ample opportunities to learn with adults who looked like them, who understood their languages and cultures. No longer confined to classrooms, students were free to draw on the wealth of learning opportunities in local parks, farms, museums, and businesses.

Schools could focus on excellent teaching and redefined what it meant to be a teacher. Adults inside and outside schools took on a variety of educator roles—master teacher, learning guide, tutor, mentor, language specialist, counselor—and worked in tightly coordinated teams, like in the medical field. Teachers’ unions embraced the opportunity to reinvigorate the profession and to make working in education more rewarding and sustainable.

Parents fully expected to help design and support their children’s learning. Those who wouldn’t otherwise have had the means received public dollars to take time off work and help students. Some worked as tutors, helping to address academic gaps. Others shared their work or hobbies to offer art, music, and career-connected learning experiences. Still others worked as navigators who helped other parents understand their children’s learning goals and find opportunities to meet them—in or out of school. Some discovered they liked working with students so much they wanted to become professional educators, and they found accessible avenues to turn their passions into new careers.

Transparency helped build trust. Parents knew their children’s individual learning goals, as well as the content and skills all students would need to master to graduate ready to thrive as adults. They had access to timely and customized reports on their children’s progress and had access to the curricula they were using—which allowed them, or any other adult who worked with their child, to support the learning process. Parents could see their students making progress and knew that if their child were to encounter obstacles, they could collaborate with their child’s team of educators on a solution. They embraced assessments as essential tools to monitor progress, identify learning needs, and address them.

Schools became joyful and challenging. Students with disabilities no longer had to choose between class time and essential therapies, because every aspect of schools, including schedules, were designed to prioritize the students with the most complex needs. Older students could participate in internships, community service projects, or work during the day and take classes online or at night. They could sleep later if they needed to or focus on classes in the morning and exploring their interests in the afternoon.

High schools became talent-development centers, where, after mastering basic graduation requirements, every student had access to career and college courses.

Realizing the lasting harm that learning interruptions could have on a generation of students, we had no choice but to ensure that evidence drove instructional decisions. Like medical providers, school systems were required to meet a basic “standard of care” that included evidence-based curriculum and proven interventions, such as high-dosage tutoring.

Choices, options, and diverse providers became core characteristics of a resilient system and necessary tools to achieve true equity. We recognized that students have diverse needs that require diverse solutions, and we designed an education system to deliver them.

If a child has a disability, comes from a challenged or unique background, or just thinks differently, we see that child as a source of untapped potential. We guarantee ways to build their unique skills and perspectives to become our country’s next leaders, innovators, and entrepreneurs.

As of fall 2027, we can say with confidence that we are ready for the next pandemic, natural disaster, or civic uprising, because our schools are built to respond, adapt, and innovate.

Like a phoenix rising from its own ashes, we rebuilt public education so all kids can become successful in America. In the aftermath of a pandemic, we have done something truly remarkable.

How CRPE will help

The Center on Reinventing Public Education is committed to tracking and reporting data on pandemic recovery as well as tracking and reporting examples of reimagining teaching and learning. This report is the first of a series of annual reports we will produce each fall through 2027. In the coming years, follow along with CRPE’s growing recovery agenda.

- The Evidence Project, our collection of pandemic-related data on schools and families, will soon begin highlighting the latest nationwide research on academic and social recovery. Keep up by subscribing to the free newsletter, or use keywords to search our research tracker.

- CRPE has also collected and analyzed an extensive set of data on school district policies and actions during the pandemic. Only a small portion of those data are referenced in this report; readers can access reports on specific topics and can search records by district or city on our website.

- We’re also committed to identifying the most innovative new schools and highlighting what they’re doing differently, especially when it comes to helping marginalized students succeed. The Canopy project, a joint effort between CRPE and the education nonprofit Transcend, features innovative school models that hold promise for replication and expansion.

- Another extensive project detailing pandemic learning pods and hubs offers important ideas for larger school systems to consider. Families and teachers value those ideas, our national survey suggested. In the future, we’re planning to explore new approaches to learning that arose inside and outside traditional education systems, before and after the pandemic.

- For promising ways districts and states are spending their federal dollars to support recovery and reimagining, visit the EduRecoveryHub, cosponsored by CRPE, the Collaborative for Student Success, and the Edunomics Lab.

- For big ideas about how to move to a more joyful, equitable, and resilient education system, see CRPE.org and—in particular—our 25th anniversary series, Thinking Forward.

Finally, please contact us at crpe@asu.edu if you’d like to engage with us on any of these projects, have updates to the data presented in this report, or have questions about our research.