When you picture a student with a disability, what image comes to mind? Is it the student in a wheelchair? Do they have Down syndrome? Are they able to speak clearly? Often, when we think of students with disabilities, we think of children who look, sound, or behave differently from “typical kids.”

However, what we often picture isn’t reality: two-thirds of students with individualized education programs (IEPs) look exactly how one would imagine a “typical kid” to appear. They’re also not down the hall in special classrooms with the rest of “those kids.” They‘re in regular classrooms all day. They have invisible disabilities (think ADD and dyslexia) and often go undiagnosed and underserved. The result is that they are simply disengaged and bored.

According to CRPE’s recent State of the American Student report, the pandemic made academic and social-emotional outcomes worse for all students, but especially for special populations. “Students with disabilities and English learners were disproportionately affected, facing higher rates of absenteeism, disrupted services, and academic and social-emotional setbacks. While some students adapted well, most faced significant challenges, revealing systemic issues that need urgent attention,” says the report.

Unfortunately, too many educators (and parents) yearn to “go back to normal,” as if normal was adequate. Sadly, the system was broken long before the pandemic and continues to shortchange not only special populations but all students.

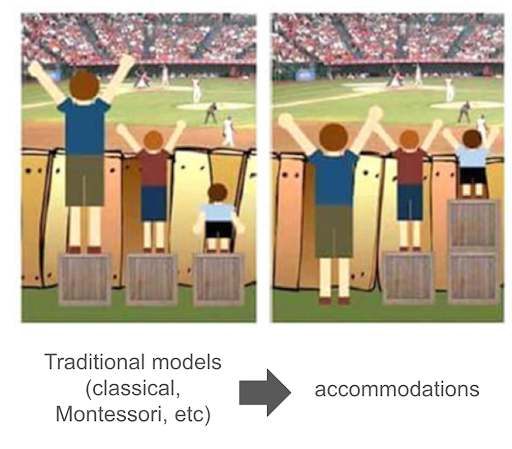

School systems have built a system of programmatic fences and different workarounds to “level the playing field.” To equalize opportunities for students who can’t see over the fence, we’ve created various accommodations (boxes) that make the playing field more visible.

From the physical separation of instructional space to differing laws, budgets, and staffing requirements, special education has been stigmatized, dividing students with disabilities and the people and resources that support them from general education students.

Can we begin to tear down these walls?

One of the first decisions prospective teachers will make when entering their preparation programs is whether to pursue a general education certificate program or a special education preparation program. They must choose whether to teach “these kids” or “those kids.” That’s absurd, especially given the makeup of today’s general education classrooms. New teachers should be prepared for a wide spectrum of learners. With their specialized training, “special education teachers” could be elevated to instructional specialists in each school.

Knowing that pretty much all classrooms have students with IEPs (and 504s), we must prepare all teachers to work with all students. Given what we learned during COVID, we need a laser-like focus on curriculum design, textbooks, and strategies based on Universal Design for Learning principles. New teachers and, quite frankly, all schools must be equipped with multiple ways to engage with students and demonstrate learning.

To be sure, some teachers will still have a standalone classroom, working with students with more significant learning needs. Others will become special education administrative specialists, spending their days dealing with the mountain of IEP paperwork. As CRPE and many others have argued, when schools design learning for the “kids on the margin,” all students will benefit.

Consider my own experience. In preschool, my daughter found it hard to draw or write. Triangular crayons (yes, that’s a thing) made all the difference. Not wanting her to stand out, I bought boxes of triangular crayons for all the students, and the teachers remarked on how beneficial they were for everyone. Teachers, parents, and students universally embraced this simple solution. Similarly, teachers in my daughter’s elementary school gave first, second, and third graders many different ways to take a spelling test, from the traditional (going up to the board or writing on paper) to the innovative (using blocks, letters, or even refrigerator magnets).

From South Carolina to North Dakota, leaders are making bold, system-wide changes based on simple solutions like these. I’ve had the privilege of meeting with many of them over the years. One consistent theme was that their efforts were grounded in a commitment to meet the needs of all students. As this begins to take hold, students with disabilities are no longer set apart. However, this also requires the reimagination of faculty roles. The Next Education Workforce Initiative at ASU’s Mary Lou Fulton Teacher’s College is a leader on this front

Meeting students where they are and providing them with the tools they need to achieve is at the very heart of special education. Personalized learning is special education, but for all students, not just some. The best way to help students recover from the pandemic is to embrace this reality.

Karla Phillips-Krivickas is the founder of Inclusive Strategies, an advocacy organization that supports the inclusion of students with disabilities in all programs, policies, and initiatives. She is the proud mother of a 21-year-old son and a 17-year-old daughter, both with disabilities.