Introduction from CRPE director Robin Lake:

I am delighted to introduce a new contributor to this blog and a new Senior Fellow at CRPE, Steven Wilson.

I have known and admired Steven for more than 20 years. He was special assistant for strategic planning for Massachusetts Governor Bill Weld and co-executive director of the Pioneer Institute, where he wrote the Massachusetts law that gave rise to one of the nation’s highest-performing charter school sectors.

He is the author of Learning on the Job: When Business Takes on Public Schools—a book that deeply influenced my studies of charter management organizations—and Reinventing the Schools: A Radical Plan for Boston.

Steven founded Ascend Public Charter Schools, where he recently led a network-wide transformation that introduced a progressive curriculum and a positive student behavior model—all while achieving remarkable outcomes for students. His recent departure from Ascend put him in the limelight in large part because, as I wrote about here, the coalition for systemic change in public education is fracturing over debates about equity, race, and who has standing. It’s extraordinarily difficult, but we must analyze and talk about what is happening and why.

To that end, we asked Steven to share lessons from Ascend’s evolution, and to reflect on the extremely difficult race, class, and equity issues schools, school systems, and policymakers are grappling with. Steven will be transparent about what he has learned in his years running school systems. But just as much, he will be open about what he hopes to continue to learn as he engages with others on these issues. For that reason, CRPE will invite writers to address these topics from different points of view.

We at CRPE have always believed inequities were hard-wired into our public education system in both obvious and insidious ways. Money didn’t flow equitably. The best principals and teachers didn’t stay in the schools that most needed their expertise. School board and district policies were too often driven by privileged parents who lobbied for more money and for the best teachers. Union and other professional association interests reinforced that dynamic by protecting low-performing adults and relegating them to the schools where the faculty and parents had the least political clout.

CRPE’s core business is studying efforts to rewire the system for school coherence, ongoing improvement, and excellence for every student—moving from the classroom, to the school, to policy implications. How can public education truly prepare every student for the challenges of the future? And how must adult practices and systems shift to make sure that happens? That’s what Steven will reflect on. We invite your reactions.

Beyond No Excuses, by Steven Wilson

It’s hard to break with something for which you have long advocated. But several years ago we knew we had to make a change at Ascend.

When we launched Ascend Public Charter Schools in 2008, we proudly called ourselves a “No Excuses” network. To us that meant a focus on results and setting every child on the path to college. A rigorous academic program tightly aligned with state standards, data-driven instruction, a longer school day, selective teacher hiring, rituals that build an esprit de corps, and a “no shortcuts” work ethic would propel students forward.

To this day, I believe No Excuses remains the most important advancement in urban schooling of our times. No reform has done more to increase academic achievement among children from underserved communities.

But along with many others in the charter sector, we came to discover the model’s failings. Rates of student suspensions and referrals were disturbingly high. Many students adapted well to rigid discipline, but others did not and became increasingly disaffected. Only a smattering of teachers managed to embody the model’s elusive ideal of strictness and warmth.

And even when No Excuses was best realized at Ascend, its ceaseless structure was doing little to prepare our students to function autonomously in college and beyond.

In every Ascend classroom was the familiar traffic light poster, a clothes pin for each child. A new day brought a fresh start, the clips tidily returned to the green circle. But then came the first infractions. The teacher stepped up to the poster and silently moved the offending students’ clips—first to yellow, a warning, then to red.

If the goal was to control behavior, the system “worked.” Rooms were orderly, teachers were able to teach, and most students learned to comply. But others exploded in rage.

At dismissal, parents swept into the school to find their children. We steeled ourselves for their overheard conversations. Here and there children animatedly shared what they had learned that day. But far more often came the same stern question from a parent: “What color did you end the day on?” The most heartbreaking such exchanges, naturally, were with children who “ended on red.” They had already received a consequence in school, yet if they answered their parents honestly, they could be punished again at home. To see a child, utterly distraught, dragged out of the building, was agonizing.

Teachers, in time, succumbed to the culture we had unintentionally created. “Your child had a great day,” a teacher might say. “Jordan stayed on green all day.”

Were we unwittingly reproducing the very school-to-prison pipeline we sought to disrupt?

And so we changed course. We set out to eliminate every echo of the criminal justice system from our schools. A true liberal education—which fosters and prizes critical thinking and independence of thought—could not be joined to a culture of rigid rule-following and silent meals. It was a flagrant contradiction. Students could not learn that their voice has power when for much of the day the school required their silence.

Princeton sociologist Joanne Golann, in a groundbreaking ethnography of one high-achieving No Excuses school, identifies the “paradox” of the school’s success: “Even in a school promoting social mobility, teachers still reinforce class-based skills and behaviors. Because of these schools’ emphasis on order as a prerequisite to raising test scores,” she argues, teachers end up stressing behaviors that would undermine middle-class students’ success.

As a consequence, Golann contends, No Excuses schools unwittingly develop what she calls “worker-learners”—children who “monitor themselves, hold back their opinions, and defer to authority.” Middle-class students are, by contrast, taught “creativity, independence, and assertiveness to prepare them for the requirements of managerial positions.”

Golann ends by asking: “Can urban schools encourage assertiveness, initiative, and ease while also ensuring order and achievement? Is there an alternative to a no-excuses disciplinary model that still raises students’ tests scores?”

At Ascend, we tried to build one such alternative.

In our lower schools, the Responsive Classroom model—widely used in suburban, middle-class schools—seeks to forge joyful classroom communities that nurture students’ sense of belonging and foster children’s social and emotional competencies. Positive language replaces warnings and threats, and students learn empathy, collaborative problem solving, and self control. In middle school, students’ desire for increasing autonomy and choice is met; students feel connected, heard, and empowered. In high school, restorative practices teach students to resolve conflicts on their own, understand the impact of their actions, and acknowledge responsibility to the school community. By the time they reach college, we hoped Ascend students would trust in their ideas and self-manage with full autonomy—and take their place at the seminar table with confidence. Ascend’s schools, we hoped, would foster agency—students’ belief that they are in control of their own lives and can act of their own free choices, their conviction that they can choose their futures.

After we adopted the new cultural model and an inquiry-based curriculum, suspension rates across middle schools fell by 48 percent from 2015 to 2018. Meanwhile, academic results shot up. Proficiency levels in English Language Arts rose by 35 percentage points over four years, and in math by 40, the fastest climb of any charter network in New York City. Ascend’s students of color closed the achievement gap with their white peers statewide—and then reversed it.

The work at Ascend is far from finished. In the high school, Ascend is still wrestling with how to infuse restorative practices into a practicable model of high expectations for student conduct and learning. But on the whole the transformation has succeeded. Rooms are orderly and joyful. Students are taking intellectual risks.

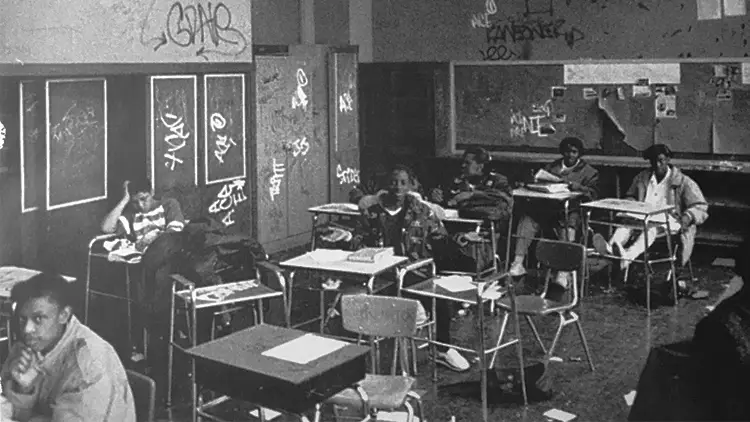

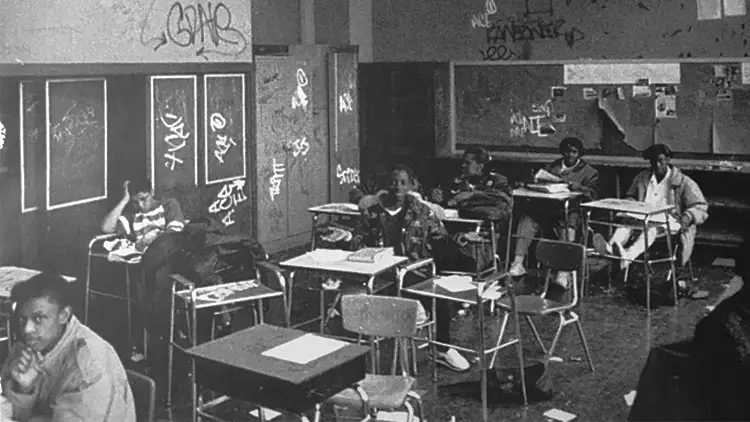

Walt Whitman Intermediate School, New York City, 1991. “No Excuses” schools offered students an escape from the staff indifference and chaos portrayed in Emily Sacher’s account of her year in an urban school. Photo reproduced with author’s permission.

We forget where we began.

In 1991, the same year Minnesota passed the nation’s first charter school law, an award-winning young education reporter in New York City decided to experience firsthand the realities of teaching in a big-city school system. Emily Sachar’s Shut Up and Let the Lady Teach: A Teacher’s Year in a Public School is her intimate account of teaching eighth grade at Walt Whitman Intermediate School in East Flatbush, Brooklyn.

When the book came out, I was just beginning my work in education policy. This week, after three decades, I picked Sachar’s memoir off my shelf. Its vivid classroom accounts and stark black-and-white photos remain devastating. Classroom walls covered in graffiti. Floors strewn with trash. An absent and indifferent principal, checked-out teachers. Virtually no curriculum, pedagogies, or measures of success. In short, a failed school. As Sachar taught, hair brushes and makeup out on desks, card games underway, balls bouncing, profanity, back-talk. On her first day, turning away from her students, Sachar was hit by a rock.

Walt Whitman Intermediate School’s squalor and indifference to its students was not an exception. In many of the urban communities where the first charter school founders proposed to open schools, district schools were chaotic, unruly, and not infrequently dangerous. Teachers struggled to maintain order, and the peer culture derogated academic achievement. CRPE founder Paul Hill, in his seminal 1990 study, High Schools with Character, reported that during class “students rifle through their purses, comb their hair, sleep, get up and walk around, even leave.” The schools’ permissiveness sought to accommodate students’ wishes, but in fact, the study found, students resented their schools’ diffidence.

Charter school founders knew that if they were to outperform district schools academically, their first task was to forge an effective school culture.

KIPP and other schools that embraced what became known as the No Excuses model offered a welcome alternative to parents, with strict order and high expectations. Educators would no longer make excuses for why students weren’t learning. They wouldn’t blame students’ families, the community, or insufficient resources. All explanations for low achievement from any quarter—especially an apologist’s appeal to demographic destiny—would be stoutly rejected. Within their four walls, they said, they had what they needed to educate all children. They would do whatever it took.

Let’s acknowledge that the term No Excuses—one devised by researchers, not educators—is unfortunate. It conjures unforgiving teachers and joyless classrooms, rather than a radical and ennobling pledge by the school’s staff to do whatever it takes to ensure every child succeeds.

Not least, No Excuses schools sought to shape their students’ values, aspirations, and choices, and to equip them with essential behavioral skills, including perseverance, diligence, and personal responsibility—even good manners. “Work hard, be nice” KIPP’s slogan urges. Today, to state such intentions is problematic. Would it still be acceptable to teach students to shake hands and make eye contact as they entered the building? Yet effective schools of every kind, serving students of every class and race, have always sought to shape the beliefs and habits of their charges. When we think of No Excuses schools today, we think first of tight discipline and high academic expectations. But their striking academic success may as much be due to their fearlessness in setting social norms.

A central premise of No Excuses school culture was that if you “sweat the small stuff, you won’t have to sweat the big stuff.” To sit for a moment with the chilling photos in Sachar’s book is to be reminded of this logic. If you allow the walls to be defaced, the furniture to go unrepaired, and the floor to be strewn with trash, that becomes the culture of the room—and invites more serious disorder. If conversely you immediately pick up every pencil and scrap of paper that falls to the floor, it sends a clear signal: This will not be our classroom. We expect more from ourselves. We believe in ourselves.

And so it is not that James Q. Wilson’s “broken windows” theory of crime prevention can’t be applied to schools. The question is, at what cost?

To leave the paper scrap on the floor, to tolerate foul language—yes, that risks sending a “nobody cares” message. But when we fetishize small matters, like citing a student for a uniform violation because his shoelaces are the wrong color, we invite troubling questions. Does the color of the shoelace actually matter? Can we truly claim that, as a broken window invites further neighborhood neglect, his offending shoelace leads the school’s community down the slippery slope to behaviors that compromise learning? And, if we were educating middle-class white children, would we have enforced such an unforgiving code?

Ibram Kendi, author of How to Be an Antiracist, describes a moment in his third-grade class. A shy black classmate raised her hand tentatively, but their white teacher instead called on a favored white student. Kendi grew incensed. At the period’s end, he refused his teacher’s call to leave the classroom. “Looking back,” he writes, “I wonder, if I had been one of her White kids would she have asked me: ‘What’s wrong?’ Would she have wondered if I was hurting? I wonder. I wonder if her racist ideas chalked up my resistance to my Blackness and therefore categorized it as misbehavior, not distress. With racist teachers, misbehaving kids of color do not receive inquiry and empathy and legitimacy. We receive orders and punishments and ‘no excuses,’ as if we are adults.”

This is difficult work. As school reformers, we wrestle with enduringly hard questions. We challenge ourselves to innovate, to do better. Despite good intentions—which, yes, do matter—we will make, amid the successes, what we come to think were mistakes. Learning will ensue. We get better. It’s not easy in these fractious, judgmental times, but we can approach our work together with curiosity, with generosity. With grace.