This piece was originally published by The 74.

In 2020-21, Albuquerque Public Schools saw an 85 percent increase in school staff retirements from the year prior. This August, it opened the school year with 300 unfilled teaching positions, and by October, its superintendent described districtwide shortages “in schools and offices, kitchens and maintenance shops. We need more custodians, bus drivers, educational assistants, food workers, HVAC technicians, security aides, substitutes and more.”

By February, New Mexico’s governor had called on the National Guard to fill vacant positions in 36 school districts like Albuquerque. Just this month, she signed a bill to increase teachers’ and counselors’ salary minimums by $10,000.

Albuquerque is certainly not alone. The National Education Association reported the ratio of hires to job openings in the education sector reached new lows across the nation, with 0.57 hires to every open position.

Our analysis of district information and local media reports finds 93 of 100 large and urban districts have mentioned staffing shortages in the 2021-22 school year. Like Albuquerque, many have struggled with staffing well before January’s Omicron surge. They face shortages in long-established roles needed to keep schools running as well as new positions made possible by federal stimulus funding. This is not a new phenomenon but an exacerbation of shortages and declining interest in teacher prep programs less visible in years past.

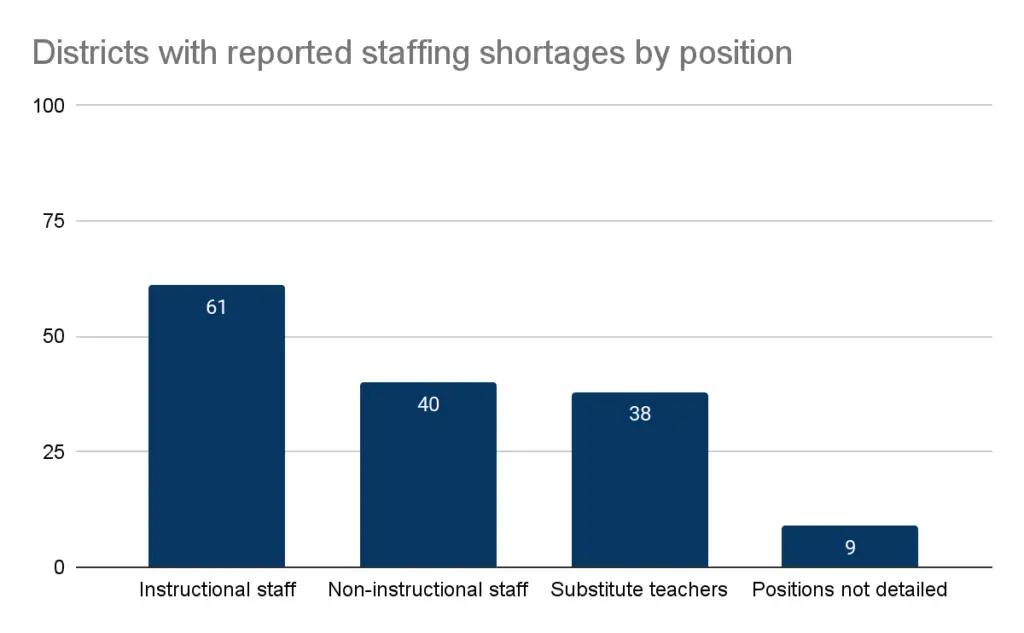

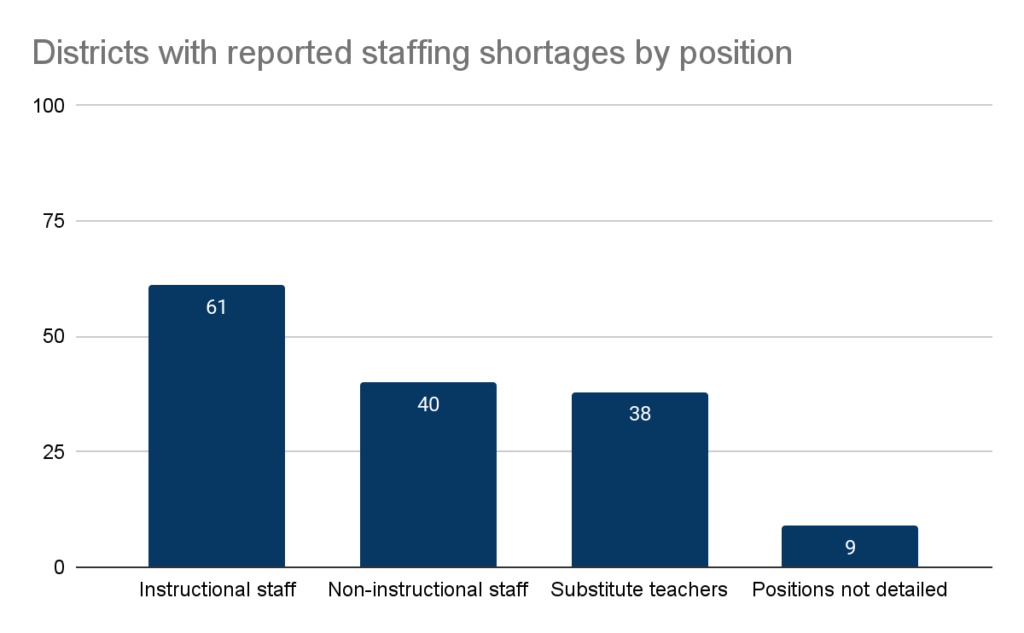

About half of these districts — 48 — are experiencing shortages across multiple departments and positions. The most common shortfall reported is instructional roles, with nearly two-thirds of districts (61) struggling to fill teaching or instructional aide positions.

Shortages have led districts to get creative in filing positions. In South Carolina, Charleston County School District increased pay in hopes of recruiting more substitute teachers. Fairfax County Public Schools has extended subbing opportunities to local college students who are hoping to make extra money and may be interested in joining the profession long term. Anchorage Public Schools gave $2,500 bonuses to hourly workers and offered “unlimited” referral bonuses to employees.

Staffing shortages are the big risk facing school stability now, more than a new variant

Districts demonstrated a more universal commitment to keeping schools open in person this January throughout the rise of the Omicron variant. Unlike the fall, the majority of large districts stayed open even amid daunting community and school infection rates.

Most of the large and urban districts we reviewed shortened quarantine protocols in 2022 in an effort to keep students in school — a shift that aligned with updated December guidance from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reducing recommended quarantine periods to five days. Of the 100 districts we review, 66 have limited their quarantine policies to seen or fewer days, compared with just four districts reviewed in September 2021.

The challenge that districts now face — and have less control over — is whether in-person classes are consistently staffed. As many signs point to reduced COVID transmission and increased student health and safety, the focus must shift to addressing the latest collateral damage to an already-embattled profession.

Fourteen of the 100 districts we reviewed experienced actual or threatened student or staff walkouts, and two saw protests from both students and staff during early 2022.

In eight of the districts, students protested or walked out. Boston Public School students walked out in January in a call for a return to remote learning and more safety protocols. And thousands of New York City Public Schools students staged a walkout demanding remote learning.

Six districts experienced staff sickouts and protests. Birmingham City Schools transitioned to remote learning at the end of January due to staffing shortages. Oakland Unified School District closed 12 schools due to teacher sickouts.

Chicago Public Schools faced both teacher and student walkouts at the start of the year, causing multiple school cancellations.

While protests may have focused on health protocols at the start of the Omicron variant, they may also be a harbinger of fraying teacher morale. New data suggest the number of teachers and administrators leaving the Chicago school system is rising.

Continued low morale, if left unaddressed, threatens to break the public school system’s promise that every student — especially the most vulnerable and marginalized learners — will have consistent access to teachers who are engaged, responsive and consistently providing high-quality learning.

This moment demands a rethinking of teaching and working in schools

Educators attribute the recent years’ exodus to things like displeasure with remote teaching, mounting stress over quarantine protocols and lack of substitute teachers, low pay and the appeal of other jobs that may feel more flexible and feasible after two years of pandemic-disrupted schooling. Combined with an already aging workforce and pre-pandemic declining enrollment in teacher preparation programs, COVID-era working conditions have only exacerbated a mounting phenomenon long facing districts.

Schools, often locked into rigid contractual agreements and subject to inflexible state policies in areas like certification, salary and the length of the instructional day, are finding it hard to compete with a flourishing gig economy and new remote working conditions that offer more flexibility and options to workers, often for more pay.

The moment calls for bold reconsideration of some assumptions about the teacher workforce, and coordinated action across the local, state and federal levels. Without some change in approach, public education risks becoming a second-rate profession and schools a routinely destabilizing force in children’s development.

Here are some suggested courses of action:

Expand grow-your-own pipelines that attract a broader, more diverse pool of talent. Districts or states must create a formal path for new employees who may not meet certification thresholds to start as hourly staff and progress into school and central office leadership roles as they gather experience, certifications and responsibility. Such programs could provide introductory courses in high school, paid summer internships in college and financial incentives to recruit graduates back to work in the schools they once attended. Districts could also increase the appeal of harder-to-staff positions like substitute teachers and bus drivers by offering these workers clear pathways to better-paying jobs as professional educators. The federal Department of Education, which has sympathized with the plight of districts and teachers, could play a greater role in incentivizing pipeline programs or coordinating best practices across states.

Demand that state leaders and labor agreements reduce barriers to entering the profession. Districts need more flexible teacher certification requirements and school day scheduling options. Certification standards should reflect an updated understanding of what teachers must know and be able to do to provide students with a well-rounded and holistic education. State certification requirements should especially acknowledge the work logged by “informal educators” who stepped in during the pandemic — community organization staff and parents who led their children’s education outside the classroom. Similarly, while well intended, rigid instructional minute and daily schedule requirements prevent districts from shaping a work environment that offers the autonomy and flexibility more students and teachers alike have come to expect as remote collaboration transforms other aspects of work and life. Adolescents are just at risk of leaving school as teachers are, as employers now offer $15-an-hour minimum wage jobs that compete for their time during the traditional school day. Districts have to be able to move outside the box of the standard 8-to-3 school day to offer attractive options to teachers looking for flexible schedules and students looking to join the workforce while completing high school.

Create more diverse working environments that create more diverse learning options for students. The role of the teacher must be re-examined. Arizona State University and its partner districts are reconfiguring the role of a singular “teacher” into coordinated teams with specialized positions, reflecting the diverse array of skills needed to holistically support the whole child. Districts have the opportunity now to pilot long-term, high-quality remote school options, creating new working and learning environments that can appeal to educators who have developed new preferences and might otherwise leave their classrooms.

Indianapolis Public Schools began this work last spring, authorizing two new district-affiliated public charter schools, partnered with community-based organizations to reflect student and community needs, to provide a permanent high-quality remote learning option. Guilford County Public Schools has established after-school learning hubs that provide personalized academic and socio-emotional support to disengaged high school students and compensate them for their time. Such approaches, currently an exception to the norm and requiring vision and bold leadership, would gain more traction were there more attention and endorsement from national education leaders.

Districts have unprecedented stimulus funds and two years to invest them in pilots of ideas like these. State leaders must step in to provide the flexibility for them to do this, and reward and promote innovative approaches. Universities must be willing to rethink educational training and recruitment to meet the changing needs of the schools they support. And the federal government must encourage state and district-led innovations that build a quality pool of future educators who can build the next generation of leaders equipped to confront the challenges that await.