Initial findings from the first month of CRPE’s in-depth reviews of district and charter school organizations’ responses to the COVID-19 crisis has revealed major gaps in learning opportunities available to students.

States play critical roles in ensuring schools address this challenge. Michigan State University’s Institute for Public Policy and Social Research in partnership with the Education Policy Innovation Collaborative recently released data that shows many states are encouraging districts to offer remote learning.

Our own review of state actions (see “About Our Analysis” below) shows that although states have indeed made efforts to offer guidance and resources to districts, too many states have yet to set clear expectations for what remote learning should look like, or are monitoring district progress.

While the crisis presents unprecedented challenges for states on multiple fronts, it is critical that states do more to clarify their expectations for what comes next. States must also ensure districts develop remediation plans to address the inevitable learning losses.

Nearly a Third of States Leave Remote Learning Entirely to Chance

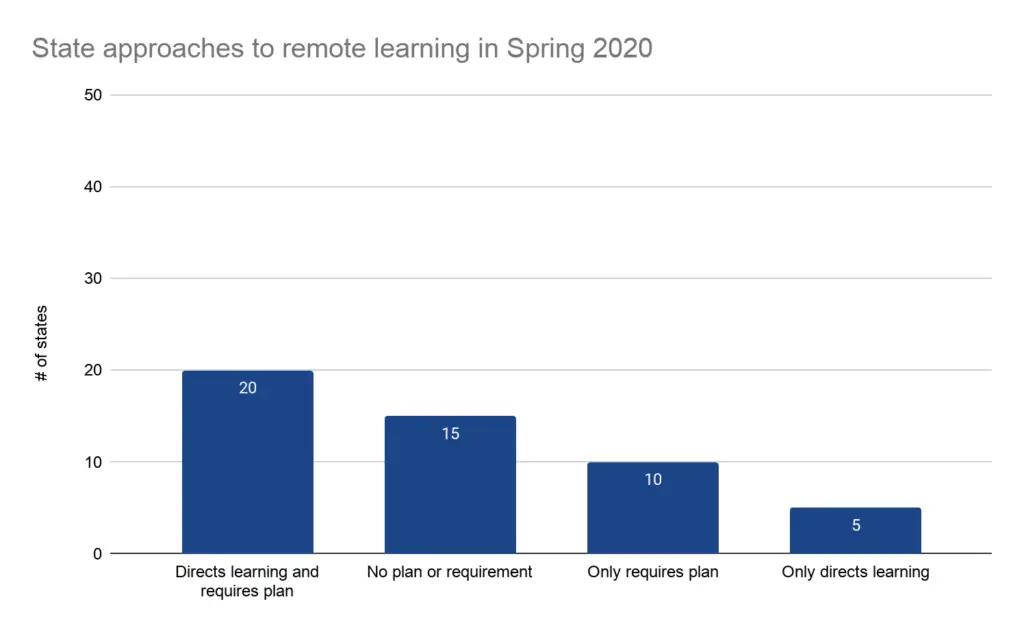

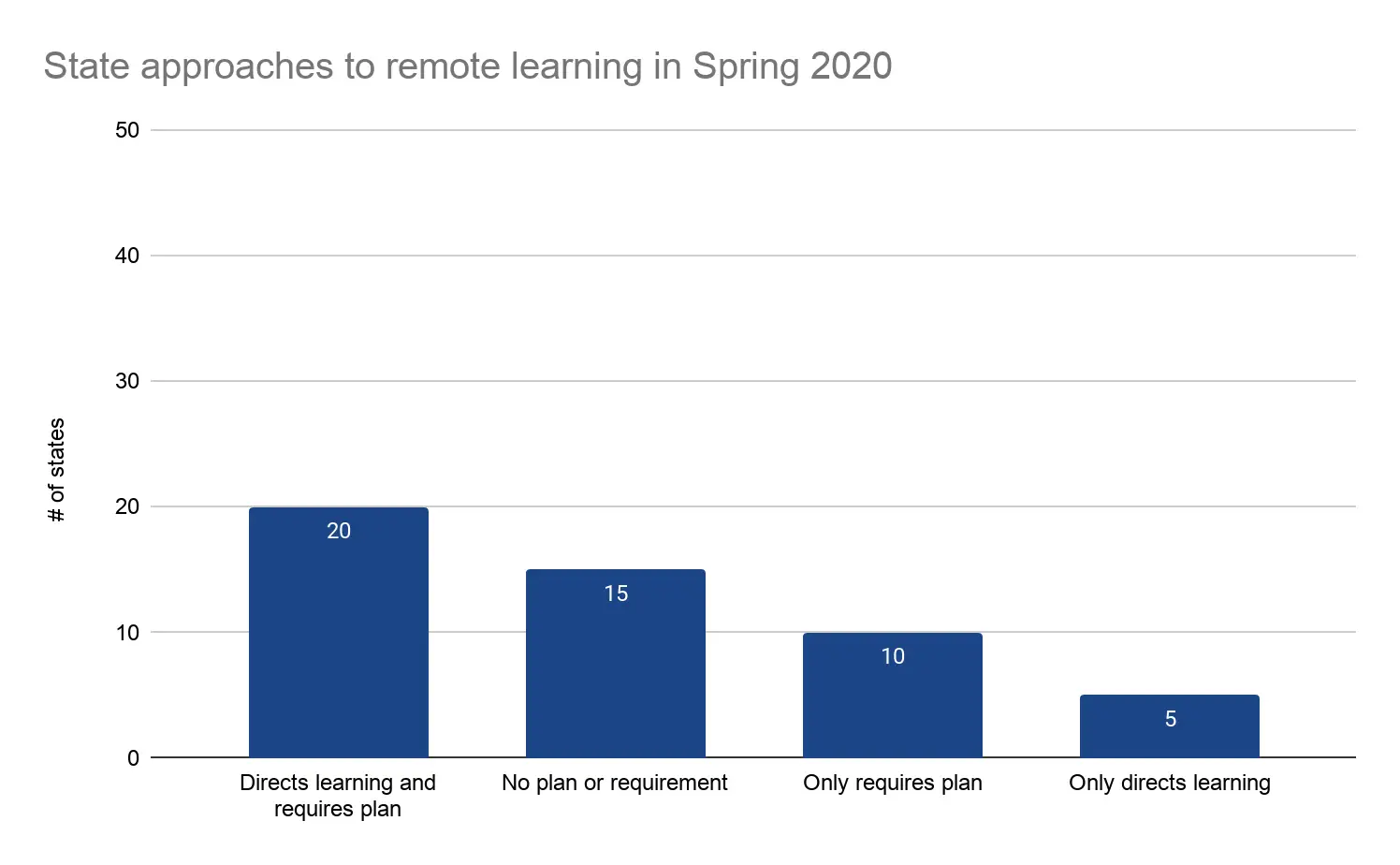

Source: CRPE analysis of state remote learning plans (see “About Our Analysis” below).

Roughly a third of states (15) have offered no official directives to require remote learning or offered a plan for instruction, instead leaving the decisions up to local decision makers.

In Virginia, schools are closed for the remainder of the 2019-20 school year. But decisions about whether to offer distance learning are left to local superintendents and school boards, though the state does offer some guidance on how districts might make up the lost learning time.

States such as North Carolina, West Virginia, and Maine simply ask districts to attempt continued learning, as much as local conditions will allow.

Others, such as Massachusetts, California, and Georgia, encourage districts to implement remote learning and provide extensive guidance to do so, but fall short of setting a requirement or publicly imposing consequences.

Based on past experience, including implementation of the school improvement provisions of the No Child Left Behind Act, leaving things up to local districts’ discretion will likely lead to a patchwork of offerings that reflect the constraints and opportunities facing different localities.

Twenty-Nine States Direct Districts to Adopt Remote Learning but Sometimes the “What” is Not Well Defined

As schools shuttered across the country, 29 states made the leap to direct school districts to offer distance learning. Colorado districts had to move to the Cloud or face the prospect of making up missed days of school all summer. Arizona, Montana, and North Dakota have threatened to revoke state funding from districts that do not implement remote learning.

We have seen some states provide clear expectations about what districts must offer. The Delaware Department of Education requires districts to provide an overview of their remote learning delivery model, by grade span, and to account for a specific number of instructional minutes and teaching days. By June 30, districts must complete 1060 hours for grades K-11, 1032 hours for grade 12, and 188 teacher days. The department provides clear examples of how teachers and students may spend their time and recommends addressing only critical standards for the remaining weeks of school. The Alabama State Department of Education has provided a checklist of requirements and options for districts to choose from. Sections require districts to outline multiple instructional delivery options, their curriculum content providers, and their communication methods and providers.

But details on what constitutes remote learning remain sparse in some of these states, reflecting what appears to be an “anything goes” approach.

- Maryland requires districts to offer remote learning but doesn’t publicly define what that is.

- Iowa offers districts relief from state instructional time requirements as long as they submit a plan outlining “any methodology used to extend learning beyond brick and mortar district building.”

- In Oklahoma, distance learning had to start April 6, but it is defined broadly as “any method of learning that happens outside the traditional school building.”

Half of All States Do Not Require Districts to Submit a Remote Learning Plan

Our review of districts’ remote learning plans tells us that school systems are taking radically different approaches to this work. Yet, half of states do not require districts to submit a remote learning plan, depriving them of a critical opportunity to ensure districts are pursuing effective approaches.

Wyoming shows that requiring plans can help drive strong district-level practices.

Districts in Wyoming had to describe planned instructional activities for all students and a method for monitoring attendance—features that remain relatively rare in our nationwide review of remote learning efforts in 82 school districts. The Cowboy state has approved all district plans, and shared some as exemplars for their peers. Districts that meet the state requirements can receive a waiver for missed instructional time, and districts that fall short could lose state funding.

States’ Infrastructure for Technical Assistance Is Uneven

Some states have invested in detailed guidance documents that summarize best practices for remote learning (see, for example, Kansas). Other state and territorial governments have launched significant technical assistance efforts to support districts and students through this unprecedented crisis, such as:

- The U.S. Virgin Islands has repurposed federal and state funds to purchase Chromebooks, ensure all students have internet access, and plan for the implementation of permanent distance learning infrastructure.

- Alaska launched a new online learning platform in a new partnership with Florida Virtual School.

- The Texas Education Agency has used funds allocated under the federal Every Student Succeeds Act to create a grant program supporting districts’ instructional continuity efforts.

But in others, such as New Jersey, Connecticut, and Maryland, publicly available support for distance learning comes primarily from a list of websites, leaving districts largely on their own to figure out how to put remote learning into practice.

States Must Help Drive Effective Remote Learning

Inequities and learning gaps are widening across district lines, and will continue to do so until more consistent expectations for student learning are established.

Students across the country are at risk of losing serious academic ground during prolonged school closures. The students whose parents can’t easily afford private tutors or who rely on special education services, and other vulnerable groups, are at the greatest risk of academic learning loss.

States must set ambitious expectations for remote learning and provide the assistance districts need to respond to the immediate crisis while preparing for large-scale remediation and continued disruptions in the fall. Inequities and learning gaps could soon widen across district lines, and will continue to do so until states establish more consistent expectations and provide meaningful support to schools and districts.

ABOUT OUR ANALYSIS

To create this review, we visited each state’s department of education website and examined other official directives. We also reviewed other compilations of state actions, such as those provided by Education Week. We present information for 50 states and 7 U.S. territories. In order to qualify as directing districts to adopt remote learning, the state had to provide clear language, such as articulating a start date for districts to begin remote learning; articulating consequences for districts that do not implement remote learning (e.g., lost funding) or incentives for districts to implement remote learning (e.g., flexibility in how mandatory instructional time is determined); or using unambiguous language, such as “must” or “require.” In order to qualify as requiring a remote learning plan, the state had to articulate an expectation, deadline, or incentive for districts to create and submit a remote learning plan. While we reviewed plans for 7 U.S. territories and Hawaii, the designations to direct districts to adopt remote learning or to submit a plan do not apply as the district is administered by the state education agency.