Nearly a month has passed since the majority of districts across the country closed.

This week we continue to track progress toward remote learning. We also look at attendance tracking for the first time.

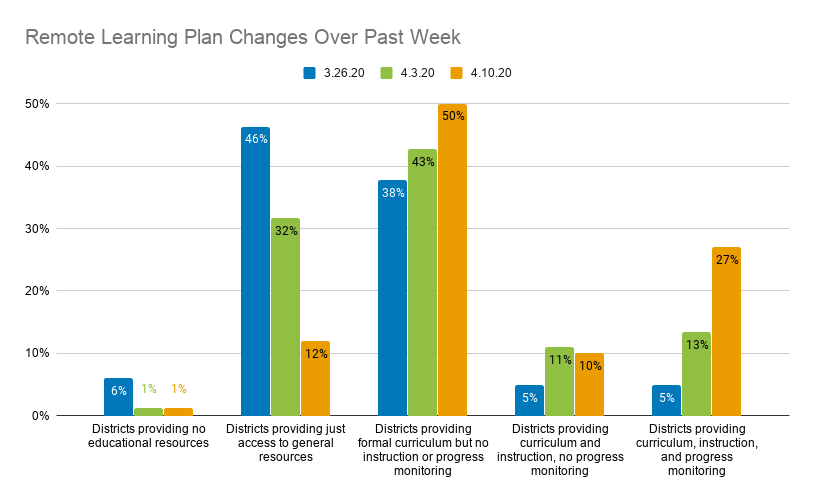

This week we saw more districts providing universal access to instruction and feedback on student work and progress monitoring. Of the 82 school districts we reviewed, 37 percent provide instruction—an uptick from the previous week. This includes 22 districts, or 27 percent of those reviewed, that provide formal curriculum, instruction, and progress monitoring for all grade levels.

Note: Out of 82 districts reviewed.

Another subset of districts provide formal curriculum and feedback on student work, but no instruction (12 districts, or 15 percent).

While the CMOs and districts we reviewed were not chosen at random and their numbers are too small to enable apples-to-apples comparisons, we do note that the CMOs reviewed still appear more likely than the districts reviewed to provide more comprehensive remote learning plans. Similar to last week, 50 percent of CMOs reviewed are providing either formal curriculum and instruction for all grade levels (1 CMO, or 6 percent) or formal curriculum, instruction, and progress monitoring for all grade levels (8 CMOs, or 44 percent). Four CMOs, or 22 percent, are providing formal curriculum and feedback on student work, but no instruction.

Almost all instruction in districts and CMOs is still asynchronous, meaning teachers provide students with pre-recorded lessons and materials, but students complete them on their own schedules. Just 9 percent of districts and 11 percent of CMOs report providing synchronous, or real-time, instruction to all grade levels.

Grading and attendance tracking systems are just beginning to take shape.

While progress monitoring has increased, the majority of districts and CMOs still do not appear to be grading work for all students. Just 26 percent of districts and 39 percent of CMOs we reviewed communicated that they were providing all students grades that would count toward a student’s academic record.

This week we examined district and CMO attendance-tracking systems for the first time. We found 17 percent of districts and 50 percent of CMOs communicate that they have some system in place to track students’ participation in remote learning.

Grading and attendance policies raise difficult questions. Districts that have these systems in place are best prepared to ensure all students are accounted for, to measure those students’ academic progress and, crucially, to start preparing now for substantial remediation efforts in the summer and fall. However, it would be unfair for districts to penalize students who cannot access online lessons because they don’t have a reliable internet connection, or whose parents may have their life upended by a sudden job loss. Some districts’ grading policies are not punitive in nature, only being put to use if it benefits a student’s final grade. For example, in the District of Columbia, secondary students can submit work to earn extra credit on their third-term grades but otherwise will not be penalized.

Remote learning plans differ across schools and age groups.

Middle and high school students typically get more access to instruction and progress monitoring than elementary students. This appears to reflect districts’ consideration of age-based learning differences, especially limiting screen time for elementary students and providing activities that require more parental supervision for early elementary students.

It may simply be easier to transition secondary students to remote learning. In some districts, secondary students already had devices or were using an online platform to communicate with their teachers. Also, district planning teams are prioritizing avenues to ensure high school students can get the credits they need to graduate or to progress grade levels. It is also likely a reflection of districts’ and CMOs’ assessment of what elementary students can manage on their own given age-appropriate developmental differences.

Almost half (49 percent) of districts we reviewed provide instruction to at least some students. Two-thirds of CMOs (67 percent) provide instruction to at least some grade levels. 15 percent of districts and 39 percent of CMOs reviewed provide synchronous instruction to at least some grade levels. Similarly, 55 percent of districts and 78 percent CMOs provide feedback on student work for at least some grade levels.

Some districts delegate decision making to schools or teachers, but still set common expectations.

About a third of districts (25 of 82, or 30 percent) and a fifth of CMOs (4 of 18, or 22 percent) indicate they are delegating some level of decision making for remote learning plans to schools or to individual classrooms.

In some cases, districts highlight clear expectations that should be followed across schools. The NYC Department of Education, for example, has released expectations for all teachers to communicate learning objectives, activities, and assignments to students weekly; interact with students real-time to deliver lessons and facilitate discussion; and archive lessons for students to access later. Teachers can then choose their instructional approaches and assignments from there.

Denver Public Schools sets expectations for teachers based on which of these options they choose: (1) support for students using district-provided instructional materials, (2) teacher-led hybrid instruction, and (3) fully digital instruction. Teachers who choose the second option are expected to select digital materials (e.g., videos, assignments from district materials or supplemental materials), which students work on and turn in independently. Teachers who choose the third option are expected to provide online instruction and to communicate with students using a phone or digital platform.

Other districts delegate decision making but do not set clear expectations, creating the possibility of greater variability across schools and classrooms. In Newark, for example, the district provided paper work packets for students to return to teachers whenever school resumes. Some Newark schools, primarily high schools, have opted to provide instruction, but this is not a district expectation.

We are just one month into the new reality of remote learning, and may not see a return to “normal” schooling for as long as 18 months. While we are heartened to see continual growth in many districts’ and CMOs’ learning plans, there is still a long way to go to ensure consistent expectations across states, districts, and schools. And formal grading and attendance-tracking systems—basic expectations for any district in a normal school year—are just beginning to return to use, inconsistently at best.

As school district leaders prepare for the end of the 2019-20 school year and look ahead to an uncertain fall, federal and state leadership is paramount. In an effort to better understand how states are shaping their districts’ approaches, this week we will launch a new state-level database and a preliminary review of all 50 states’ distance learning expectations. We are also diving deeper into a few fast-moving districts in Texas and Florida this week to better understand their complexities and conditions for success.