Last week, school reopening was thrust into the national and political spotlight as President Donald Trump polarized the issue and Betsy DeVos, his education secretary, threatened to divert federal funding from schools that do not open in-person.

Districts and states have been slow to release much detail on what to expect in the fall, but tentative plans are taking shape. Our review of some of the first U.S. districts to release more detailed information on fall 2020-21 planning shows districts are taking divergent paths.

Districts each face different health concerns, political environments, and parent and teacher preferences. They also face hard choices about how to allocate time, staffing, and resources. Some are clear about students they will target and strategies they will prioritize; others seem like they are preparing to offer the same to everyone. Most focus on operational brass tacks over clearly defined learning plans.

Most well-known districts have not yet released detailed plans. Even plans reviewed here are in draft stage and still evolving as districts consider changing health conditions and public feedback. The plans provide a preview but not a comprehensive story—yet—into what anxious parents and teachers can expect this fall.

Health and safety planning dominate districts’ 2020-21 information.

Through a national search of websites, general media, and social media we have identified 30 districts that have released draft formal plans or public planning materials for fall 2020-21. Many of these districts are well known and most are included in CRPE’s analyses of district spring and summer plans.

All 30 districts examined here provide information on health and safety, with the vast majority providing information on each of the health and safety indicators we tracked.

Nearly every plan we reviewed is taking federal and state public health guidance to heart: incorporating hand washing stations, social distancing, and behavioral norms such limiting student movement and interaction and requiring students and staff to wear masks. Anchorage Public Schools in Alaska is the only district that has posted no information about its health and safety guidelines. Grab and go food service is common in other districts’ plans, as is requiring students to eat lunch in the classroom, not the cafeteria.

A small number of districts plan to go further, staggering arrival and departure times and planning to deliver instruction in non-classroom spaces, and even outdoors, to increase physical distances between students and teachers.

Districts are planning for all contingencies, including at least some in-person learning time.

Districts provided contingency plans for at least some of the three anticipated fall learning models: opening fully in-person with social distancing, providing a 100 percent remote learning option similar to the spring, and providing a hybrid option that combines in-person and remote learning.

About a third of districts reviewed provide contingency models for all three scenarios (11 of 30, or 37 percent). Many in this group have not set a preference for one model but may be waiting on state health indicators (such as Santa Ana Unified, which details learning models for each of four stages of social distancing under the California Department of Education guidelines). Others are following state direction to plan multiple scenarios, such as Wake County Public Schools, which has prepared three models as required by North Carolina state-issued guidance, and plans to reopen schools under a hybrid model.

A significant number of other districts (9 of 30, or just under a third) are planning to open with in-person attendance, five days a week, assuming health conditions allow. They also provide a full-time remote learning option for students who opt out, but do not detail a hybrid learning scenario. Some will rely on cohorts (grouping students to stay in one classroom during the school day while teachers travel). For example, Shelby County Schools, near Memphis, Tenn., will ask elementary and middle schools to restrict student movement as much as possible, assigning them to cohorts spread across classrooms and other unused parts of buildings like the gym, cafeteria, or library.

The final third of plans reviewed—9 out of 30—are not considering full-time in-person instruction at all. Most (8 of the 9) plan to return to hybrid learning and one plans to start remotely.

All but one district (Detroit Public Schools, that cites restrictions in state law that prevent it from offering a fully remote option) are planning for a fully remote learning scenario, should they need the option.

Hillsborough County Public Schools, which serves Tampa, offers two online options: “elearning,” the district’s spring remote learning program offered via each student’s enrolled school with uploaded and live instruction, or Hillsborough Virtual K-12, a self-paced online school operated by the district that employs local teachers but relies on the infrastructure of the statewide Florida Virtual School. Miami-Dade County and Duval County, also in Florida, allow similar multiple remote learning choices.

Almost all districts plan to provide some in-person learning this fall but recent virus spread calls this into question.

Contrary to Secretary of Education Betsy DeVos’ concern that some schools will not physically open this fall, only one district we reviewed is planning a remote-only return. Montgomery County Public Schools, in Maryland, plans to open with fully remote instruction and gradually phase in an alternating-day hybrid schedule by November, beginning with younger students.

While districts stress that they are in planning mode and may adjust course, those that provide a recommendation are nearly evenly split on in-person versus hybrid models.

However, this story is likely to change as viral infection rates increase nationally. Los Angeles Unified, San Diego Unified, Atlanta Public Schools, and Metro Nashville Public Schools (none of which have released their learning plans yet) have all announced that local health conditions will require them to start the coming school year remotely.

Most districts, including those that are firmly committed to which models they will or won’t offer, provide parents an option to opt out by signing up for full-time remote learning. Miami-Dade County Public Schools is asking its parents to choose between either in-person or full remote learning before determining each school’s schedule. Schools with less than 75 percent interest in in-person instruction will have five days of classes a week, and schools with more than 75 percent interest will move to a hybrid model to reduce class size.

Districts planning for a hybrid model prefer alternating day schedules that accommodate teacher professional development.

Of districts preparing for hybrid learning, the vast majority plan on some alternating day schedule (15 of 19 that provide details, or 79 percent). Most split students into two cohorts, each receiving in-person learning two days a week and remote learning three days a week. This allows for one fully remote day (no students on campus), which typically is dedicated to teacher professional development or collaboration. It can also allow for time to sanitize buildings or provide interventions for small groups of students who need extra support.

The remaining districts (4 of 19, or 21 percent) plan on alternating weeks. Two North Carolina districts—Charlotte-Mecklenburg Schools and Wake County Public Schools—propose splitting students into three cohorts that alternate one week in-person, two weeks remote. Hillsborough County Public Schools in Florida plans to alternate weeks with one day per week fully remote to focus on professional development and intervention.

Remote learning plans increase expectations for instruction and curriculum.

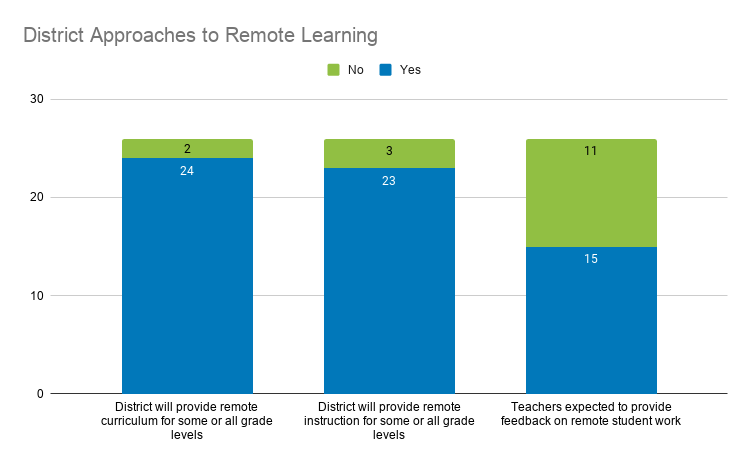

Of the 30 districts reviewed, 26 provide high-level information about fall remote teaching and learning strategies. Early plans show that most districts will make remote curriculum (88 percent) and instruction (83 percent) available to some or all students, and a little more than half (58 percent) make it clear that students in remote learning will receive feedback on work assignments.

Plans indicate districts are making improvements to their fall remote learning plans based on family feedback on the spring learning experience. Fairfax County Public Schools in Virginia cited parent feedback in its priority to increase live instruction to reduce family burden. Des Moines Public Schools shared family and student survey results by grade level rating the effectiveness of various components of virtual learning.

Also similar to the spring, where less than half of a representative sample of districts provided information about remote instruction, supporting students with disabilities, grading, or attendance, districts share little detail about how they plan to support vulnerable populations, including students with special needs, English language learners, and homeless/transitional students. Because districts do not communicate whether and how they will do remote learning differently for these populations, it is not clear whether students will receive adequate services or higher expectations this year.

It’s clear that some districts have taken lessons from the spring and are introducing more detailed expectations for 2020-21 learning than what they shared last school year.

Detroit, which did not announce its remote learning plan until mid April, was one of the first districts to release a draft plan this summer. The district’s plan details hybrid and remote learning options for students, and it has adopted a new learning management system that better facilitates remote learning, allowing students to complete remote work assignments for feedback and have two-way conversations with teachers.

Charlotte-Mecklenburg Schools, which did not offer live instruction or devices for all students in the spring, is moving to a K–12 one-to-one laptop program and will provide live and self-paced learning next year in its virtual scenario. Course specialists are designing content over the summer.

Less than half of districts explain how they will prioritize vulnerable learners to correct widening opportunity gaps.

In light of limited staffing, budgets, and time, districts are faced with a choice of whether to distribute in-person learning equally to all students, or to focus limited classroom space on groups with the greatest need for in-person support, such as younger students and special populations.

Of 26 districts with learning plans we reviewed, less than half (11 districts, or 42 percent) plan to give priority in-person access to specific types of students. Seven of these prioritize serving younger grade levels, such as Columbus City Schools, which plans to serve only K–8 students in person, with high schoolers fully remote.

Eight in this group plan to prioritize students who have fallen behind academically or have specialized needs, such as students with disabilities or those who are learning English. Fairfax County Public Schools plans to follow an alternating day hybrid schedule that reserves one hour a day for four days a week and one full day a week to provide remote interventions for students with disabilities and English learners. Schools are asked to collect and monitor student data to refer more students. Support staff and resource teachers will provide interventions.

Duval County Public Schools in Florida currently models both priorities, but is revising their plan to meet new state guidelines. Its hybrid schedule offers elementary students up to five days of in-person instruction, middle school students three to four days, and high school students two days. Students with special needs will receive in-person instruction five days a week except on a case-by-case basis.

Priority access to in-person instruction is a common strategy deployed by other countries moving to remote and hybrid learning as well.

Districts that draw a line in the sand about their priorities both acknowledge our current reality and set themselves up to strategically and more equitably address gaps that widened over the spring and continue into the fall. This is imperative given the health, political, and social crises of the past half year and the urgency to approach things differently in 2020-21.

We hope this first look can inform other districts’ planning. We will continue to add and update database information, in alignment with our district planning tool, and go deeper into examples and innovative approaches in subsequent posts.