A $189 billion infusion of federal COVID relief funding gives America’s school districts an unprecedented opportunity to invest in lasting improvements in public education and make their students whole after a year and a half of disruptions.

To understand how districts are seizing this opportunity, researchers at CRPE reviewed initial plans for Elementary and Secondary Schools Emergency Relief (ESSER) spending in 100 large and urban districts. We also reviewed how they are engaging the public in their decisions. Districts are beginning to signal how they will spend the funds, but most are still short on details; 71 percent provide at least some information.

Our review finds few plans, at least so far, to invest stimulus funding in ways that will address long-term systemic challenges. Nearly two-thirds of districts we reviewed do not make clear how they will meet another key mandate in the federal relief legislation: gathering meaningful input from their communities to shape their spending decisions. Only 39 percent have a publicly transparent process in place for receiving and using public input.

Districts appear to be doubling down on what they know: more time, more staff, more capital spending

Districts are not yet sharing plans for their entire federal stimulus allocations. At most, they share what a portion of funds would support. For example, Chicago Public Schools has released a detailed plan that apportions $525 million of its $1.8 billion estimated ARP funds. This may be because districts are waiting on public input, or reserving funds for future school years.

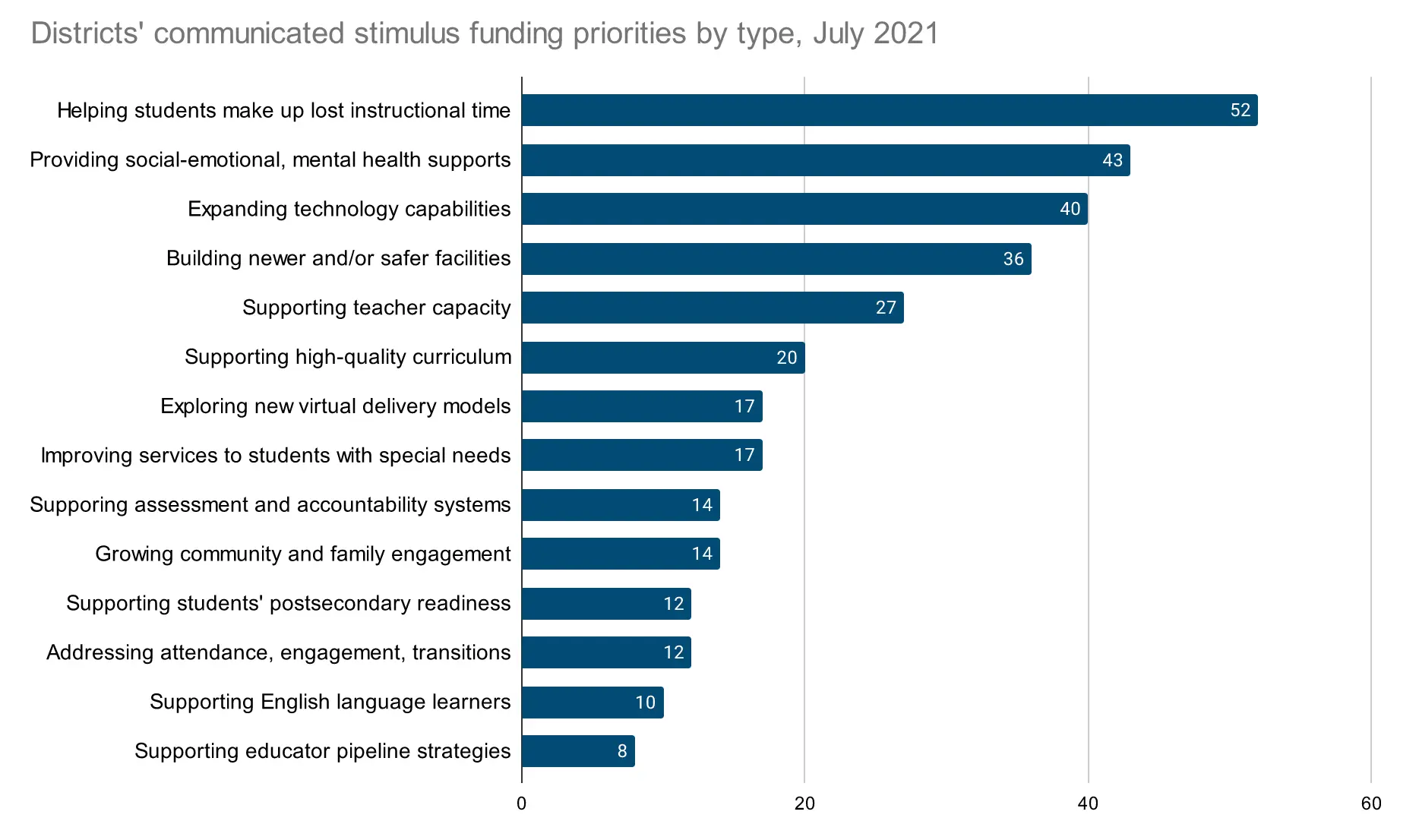

Currently available details suggest many districts are prioritizing investments to help students recover from the pandemic. More than half (51 percent) say they’ll allocate money to make up for lost instructional time, and more than four in ten (43 percent) plan to invest in social-emotional support for students. Districts also signal they will invest in technology (40 percent) and facility upgrades (36 percent). The least common priorities mentioned were investing in teacher pipelines (8 percent), addressing student engagement or attendance (12 percent), and students’ postsecondary readiness (12 percent).

Only 8 percent of districts mention attendance or student retention as a goal. One of the few districts signalling this priority, Miami-Dade County Public Schools, is mounting a public student attendance and enrollment campaign and hiring hourly attendance and enrollment specialists at schools.

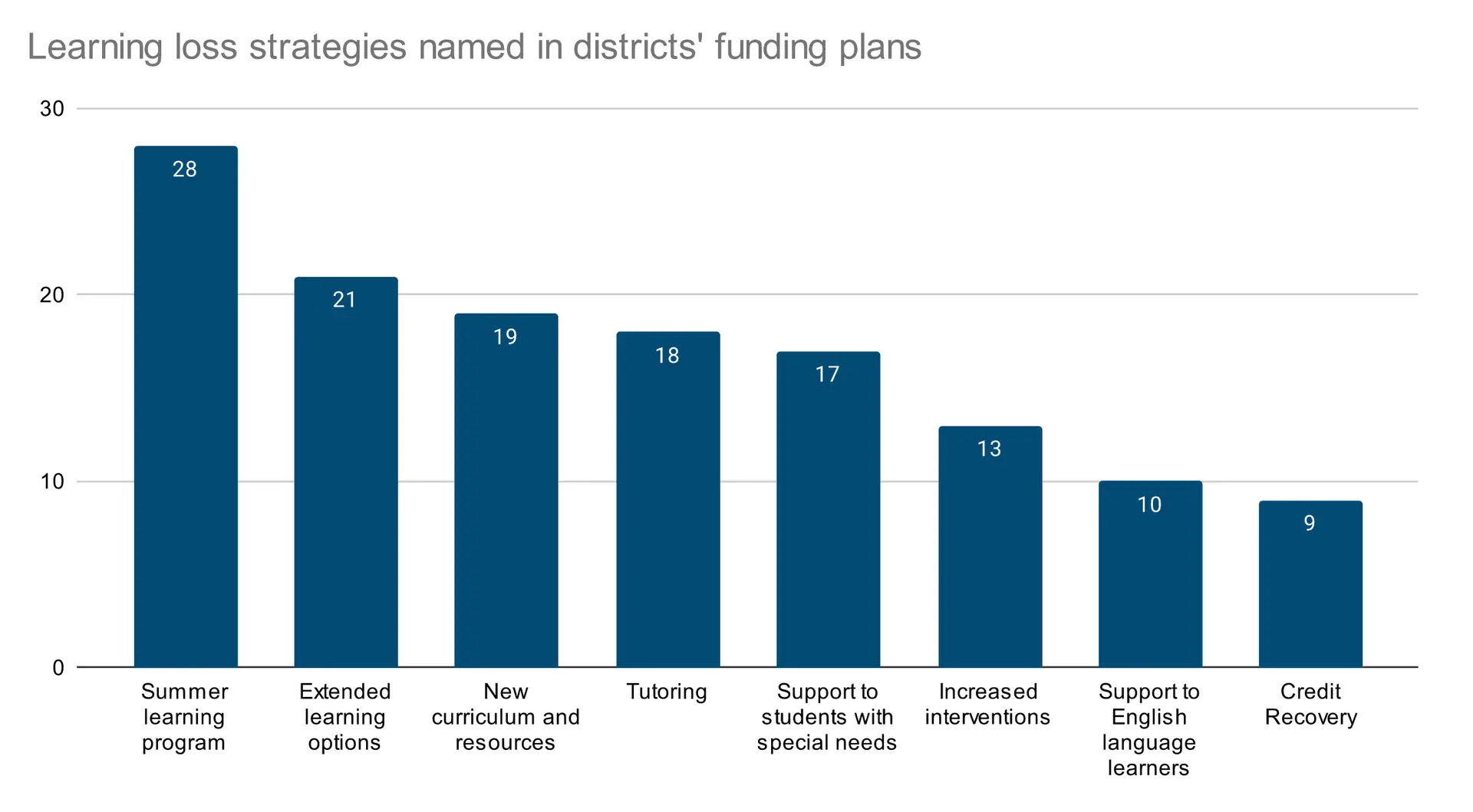

The COVID relief law requires school districts to invest at least 20 percent of their ESSER III funding in efforts to make up for lost learning time, so it is surprising that only half of districts name it as a priority. The most common strategy districts mention is increased instructional time, either through more robust summer programming or extended learning options during the school year. Other strategies include new curriculum, tutoring, and academic interventions. Also surprising: only 17 percent of districts explicitly commit to improving services for students with disabilities—many of whom suffered without access to legally required special education services during the pandemic—and just 10 do the same for English language learners.

San Antonio Independent School District plans to add the equivalent of 30 school days through its JumpStart summer programming and intercessions throughout the year. The initiative will start with a two-week intersession beginning July 19, and hold additional classes on five select Saturdays, a week in January, and two weeks in June. The plan would run for the next three academic years and four summers. Intercessions will be used for credit recovery, enrichment, and social-emotional learning.

The School District of Philadelphia is supplementing a $2 billion planned, six-year capital investment campaign with $325 million of ARP funds, approximately the same amount it will commit to accelerating learning and supporting academic recovery ($350 million) and substantially more than the $150 million designated for social-emotional supports. The district’s facilities are notoriously in need of repair, but 2019–20 data show that 19 percent of Philadelphia students achieved college readiness benchmarks on either the SAT or ACT, and 29 percent of students report feeling ready for college—calling into question whether building upgrades are the most urgent priority for such a large chunk of recovery funding.

A substantial portion of districts are considering continuing or expanding virtual school options this fall. Of 100 large and urban districts reviewed this spring and summer, 40 plan to offer such programs. Of those, 17 explicitly plan to use ESSER funding to support virtual learning options. Norfolk Public Schools, for example, will continue its NPS Virtual Scholars Academy, whose curriculum and pacing will align with the district’s in-person instruction once schools reopen.

The question for districts investing in virtual education is whether these options will simply replicate the full-time online schools that often achieved dismal academic outcomes before the pandemic, or continue pandemic-era online learning experiences, which worked poorly for many students. If so, districts will need to carefully monitor whether students who participate in online options are succeeding academically. They should also follow the lead of Indianapolis Public Schools, which is creating new partnerships that give online students access to small classes and targeted in-person support.

Districts are not transparent about how they are gathering and using input from the public

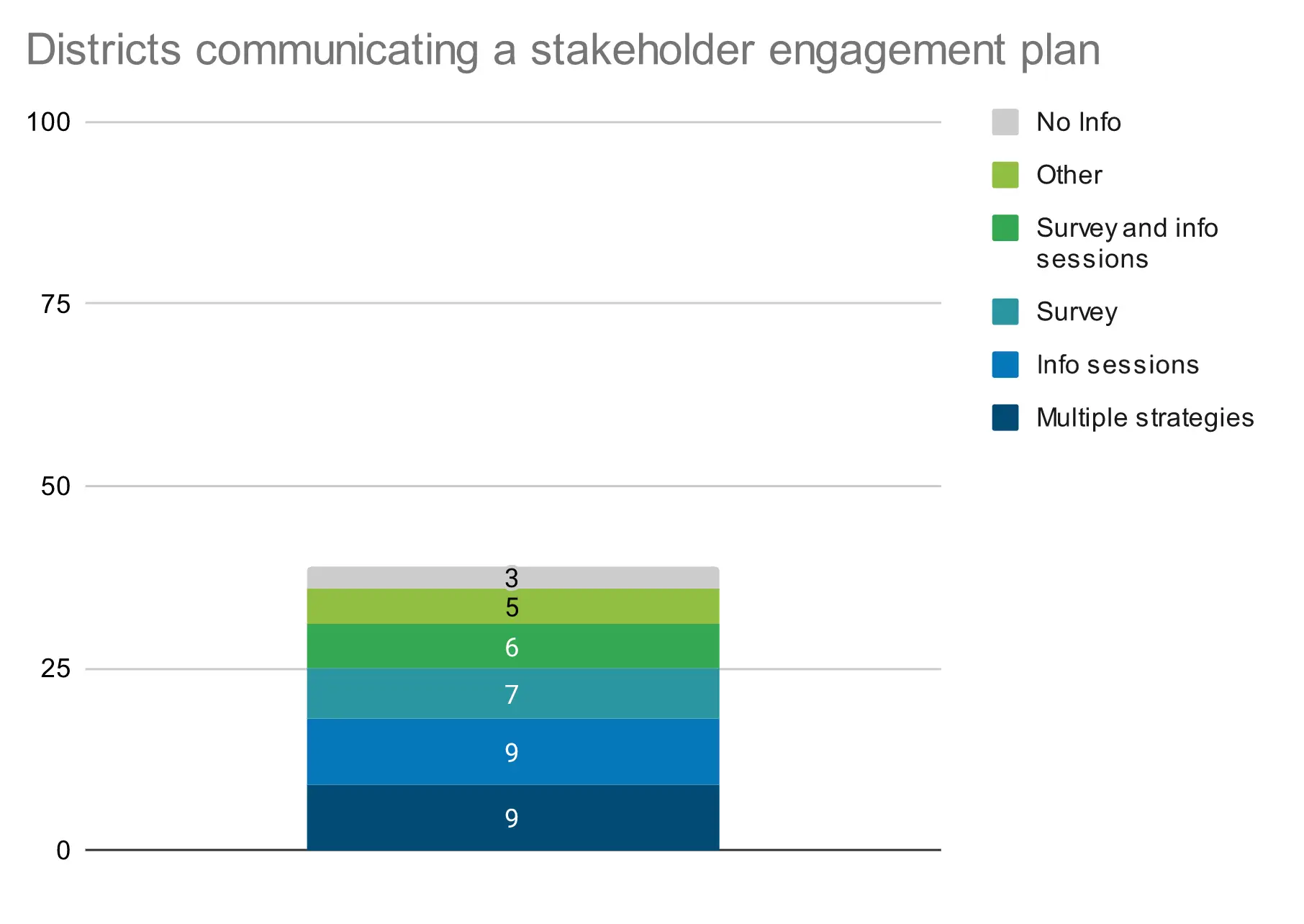

Despite the federal law’s requirements that school districts take meaningful input from the public, only a little more than a third of districts in our review (39 percent) have clearly communicated how they intend to do so. Of those that have, surveys and information sessions are the most common strategy for gathering input.

Presenting ideas in community meetings, or taking a statistical snapshot of public sentiment through a survey, may not be enough to assure the public that their concerns are shaping district priorities. But some districts are building more transparency into the process. Baltimore Public Schools conducted surveys, including a student survey, and held community input sessions in May and June to guide its plans. The district also published detailed results from those feedback sessions, so the public can compare how their input actually aligns with the district’s spending decisions.

Boston Public Schools convened a commission dedicated to setting stimulus spending priorities in May and June. A 30-day review and comment period began July 1 on the commission’s final recommendations to the superintendent. The commission has proposed efforts to ensure spending is equitable, including an “Opportunity Index” designed to identify and direct more resources to schools with higher concentrations of students in need.

In one noteworthy step toward transparency, Indianapolis Public Schools created a public website, which it plans to update quarterly, where the public can track its federal stimulus spending.

The majority of districts seem to be steering clear of long-term budget commitments with stimulus funds

One-time federal stimulus funding raises the possibility that some districts will make spending decisions that create unsustainable long-term funding obligations. Most of the districts in our review appear to be avoiding this misstep—with some exceptions.

Fourteen districts have announced teacher salary increases or bonuses, and five have committed to reducing class size, strategies that can create long-term funding cliffs when grant funds dry up in three years. Two districts—Detroit Public Schools and Shelby County Public Schools—plan to do both. Detroit Public Schools is using ESSER funds to offer one-time bonuses and hire additional teachers in order to lower class sizes in the short term. While the district’s plan says positions supported by relief funding will expire when the federal money runs out, it notes that new hires will help build up its bench of teaching talent.

Other districts have made clear they plan to use the new funding to plug holes in their budget, or perhaps, to delay a reckoning with future budget cuts. Anchorage Public Schools’ proposed budget would use ESSER funds to maintain staffing levels despite enrollment drops during the pandemic—a move that could place the district in a precarious financial position if students who left for private or homeschool options don’t return as hoped. Denver Public Schools is using funds to offset a budget deficit. Its chief financial officer says the district will gradually wean itself off the federal money over the next three years, but provides no detail.

Can districts seize the moment?

In the face of unprecedented national declines in enrollment and academic achievement in 2020–21, and equally unprecedented federal aid, districts have not just the opportunity but the obligation to do something different, new, and better for students and communities. This first review of districts’ signaling of priorities shows us that there are missing pieces in many places.

This early review also shows worrying signs that a fear from this spring is coming true: the high volume of funds, a short summer timeline for developing plans, and lack of capacity to authentically engage families, teachers, and community groups could make it impossible for many districts to enact the change needed to ensure their students recover from the pandemic—much less rebuild a public education system more responsive to their needs.

But there is still time. Districts are still working to finalize formal plans for their ESSER III funding, which are due to states in late summer. We will undoubtedly learn more about districts’ vision for recovery over the next few months. And this fall, we will learn how well their plans translate into practice.

CRPE will continue to report findings on districts’ early priorities for federal stimulus funding priorities in the coming weeks. Please reference our publicly available database and send any inquiries to crpedatabase@uw.edu.