Homeschooling in America is changing.

In the 1980s and 1990s, it took hold mostly among white religious conservatives. They rejected secular public education and wanted to educate their children on their own terms.

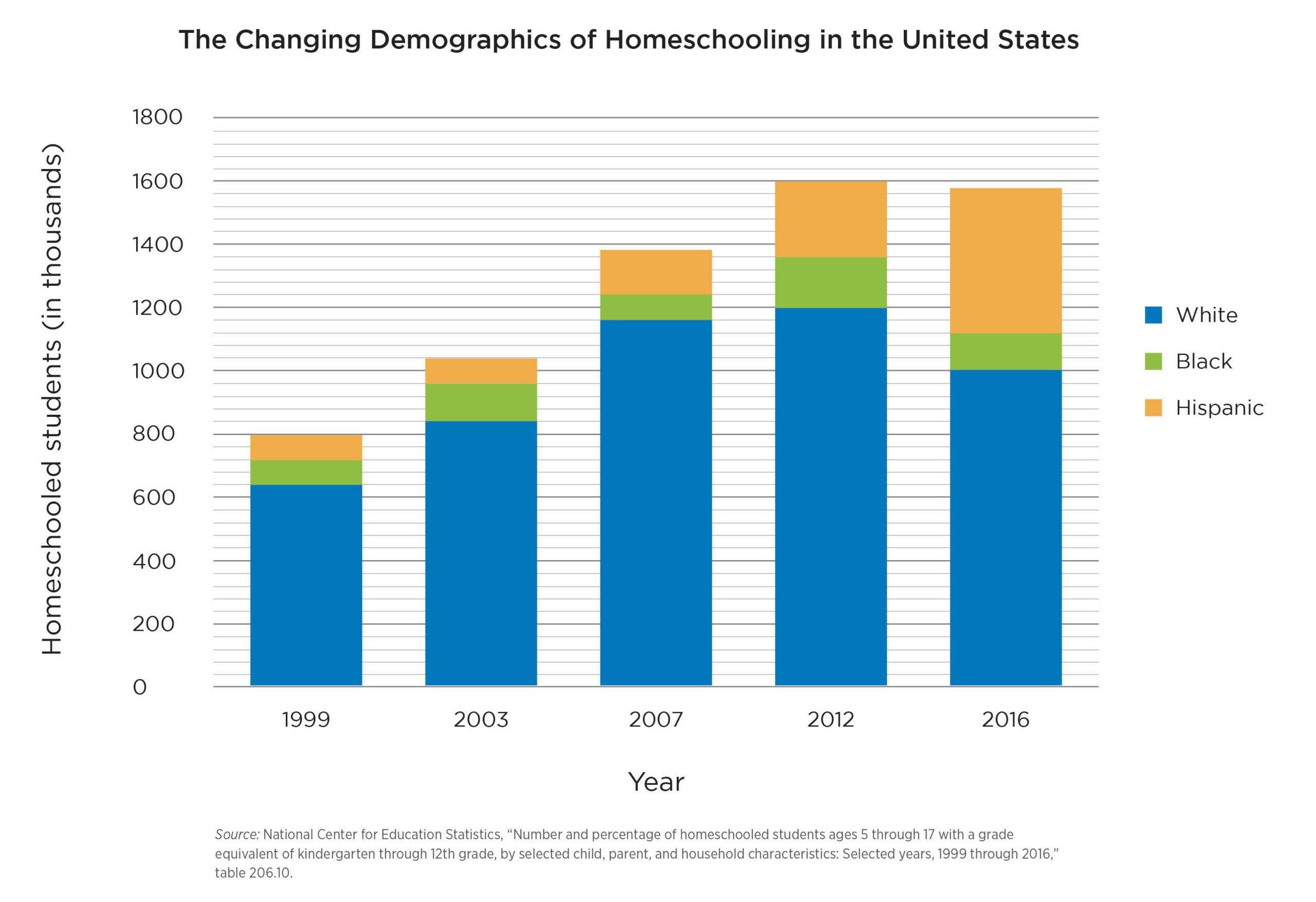

As a new CRPE research brief shows, homeschoolers are becoming more diverse, and so are their motivations. The ranks of black and Hispanic homeschoolers have grown dramatically. Parents of students with disabilities have developed customized programs of therapy and support. Some LGBTQ youth have taken to homeschooling to escape bullying and peer pressure.

This shifting landscape might hold lessons for public education as a whole.

A growing infrastructure has made opting out of traditional schooling more feasible. Online resources make it easier for parents to find effective curricula. Parents who don’t feel equipped to teach AP Calculus can enroll their students in a part-time online course.

Co-ops allow parents to curate courses, enrichment opportunities and chances for students to socialize. Microschools and part-time schools offer lower-cost alternatives to private school. Homeschool assistance programs let parents supplement their at-home instruction with courses taught by licensed teachers.

Arizona, Florida, North Carolina and Tennessee have created education savings accounts that enable some parents to supplement at-home instruction with enrichment and specialized tutoring paid for with public funds.

Right now, approximately 3 percent of American students are homeschooled—though more may be enrolled as public school students in full-time virtual programs that look a lot like homeschooling in practice.

These families likely have advantages that allow them to participate: teaching their own children takes time, know-how and, in many cases, money. They also likely make sacrifices, such as quitting jobs to be at home with their children or spending money out of pocket to pay for textbooks and online classes.

Parents also have unique motivations. They might be desperate to escape bullying, racism or school environments ill-suited to children with special needs. Or they might see value in creating a learning environment where younger children learn from older brothers and sisters. Perhaps families want to unlock learning experiences, like cross-country road trips, afternoon trips to the museum or immersion in the arts, that don’t fit neatly into a traditional school schedule.

In other words, these parents might be early adopters of new approaches to education that can allow us to rethink what school looks like, or where and when learning can happen.

Lots of people in public education are re-examining fundamental features of schooling. In schools that embrace personalized learning, many students immerse themselves in projects that blur the lines between subjects or take them outside the school walls. Many innovative career and technical education programs have no choice but to engender creative thinking about how students use their time. A few out-of-the-box models even depend on students completing some coursework on their own time, outside the normal school day.

As more educators try to develop a new grammar of schooling, homeschoolers—and the support systems they have devised—offer an intriguing example of zero-based thinking. They are assembling learning opportunities for their children, free of the assumptions that have shaped schools for more than a century. Studying their efforts might help us consider: What would public education look like if we had to build it, today, from scratch?

Exploring this question will quickly lead to difficult but important questions about what public accountability should look like. Dismal outcomes from full-time online schools suggest that leaving students and learning providers entirely to their own devices can have serious downsides. We must also explore challenging questions about what kinds of learning opportunities should be supported by public funding and how that funding should be allocated. And we will have to consider new dimensions of educational inequality. For some parents, homeschooling might not be feasible. How can we ensure that their children still have access to customized learning opportunities?

We can’t wrestle with these difficult questions before we understand what’s out there. We must chart the landscape of homeschooling to learn how families are customizing education for their children, which support structures best help low-income parents and what innovations in teaching, learning and social-emotional development might be tucked into homeschool cooperatives and communities. And we must understand the growing panoply of providers that blur the lines between learning at school and learning at home.

Right now, there’s a shortage of data on exactly who homeschools, and why, and what the experience looks like. Getting a clearer picture may unlock insights that can improve education for every student.

The blog originally appeared in The 74.