This piece was originally published by The Brookings Institution’s Brown Center Chalkboard.

The 2022-2023 school year’s staff shortages have dominated back-to-school conversations and gained the attention of the Biden-Harris administration. While educator shortages existed before the pandemic, this year’s recruitment challenges have been marked by increased teacher stress and burnout, additional positions to fill, enrollment declines in teacher-training programs, and competition from other job sectors.

Nearly all of America’s 100 largest districts reported staffing shortages in spring 2022, according to a previous analysis by the Center on Reinventing Public Education (CRPE). At the time, many districts were struggling to fill instructional roles due to the rise of the Omicron variant.

As part of CRPE’s ongoing review of how large districts are responding to the pandemic and planning to spend their federal COVID-19 relief dollars, we looked into how districts are planning to address staff recruitment and retention challenges. To do so, we reviewed districts’ proposed federal spending plans and annual budgets and publicly posted recovery strategies to assess how they’re investing in their workforce.

We found that only about half of large U.S. districts are planning to bolster staff recruitment efforts—by training local talent, offering bonuses, or creating more flexible job roles, according to our recent of district spending plans. Nearly all large U.S. districts, however, said they planned to expand staff training, according to our review—even though it’s not clear how well professional development drives staff retention.

Professional development is the most common strategy to support staff

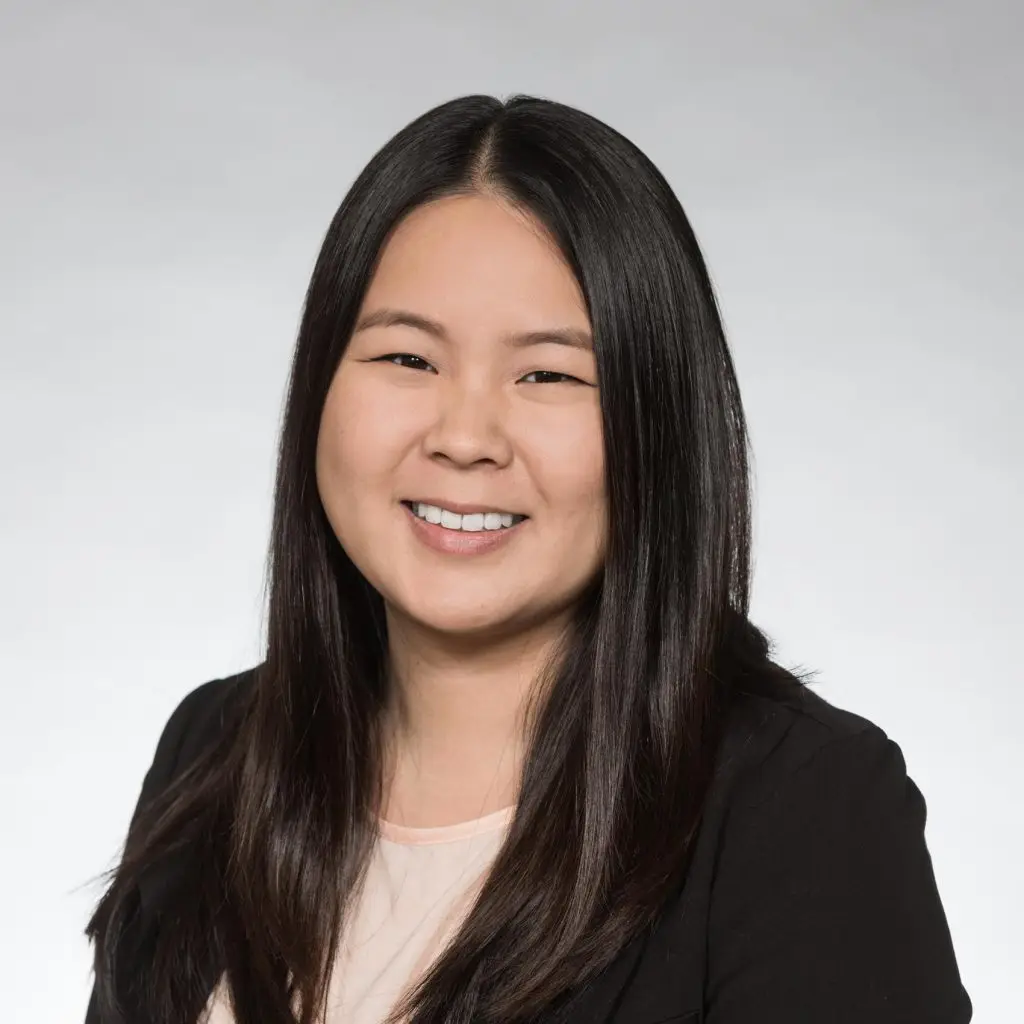

Of the 89 large and urban districts that publicly communicated new plans to support workers, 84 said they would offer more professional development opportunities. Only about half (52), said they planned to invest in recruitment strategies, such as “grow-your-own” pipeline partnerships, hiring bonuses, and relaxing teacher certification requirements. Fewer than half of the districts (42) said they planned to offer retention bonuses.

Far fewer districts said they planned to invest in coaching and mentoring (26) or staff well-being programs (26).

Most staff training geared toward academic support

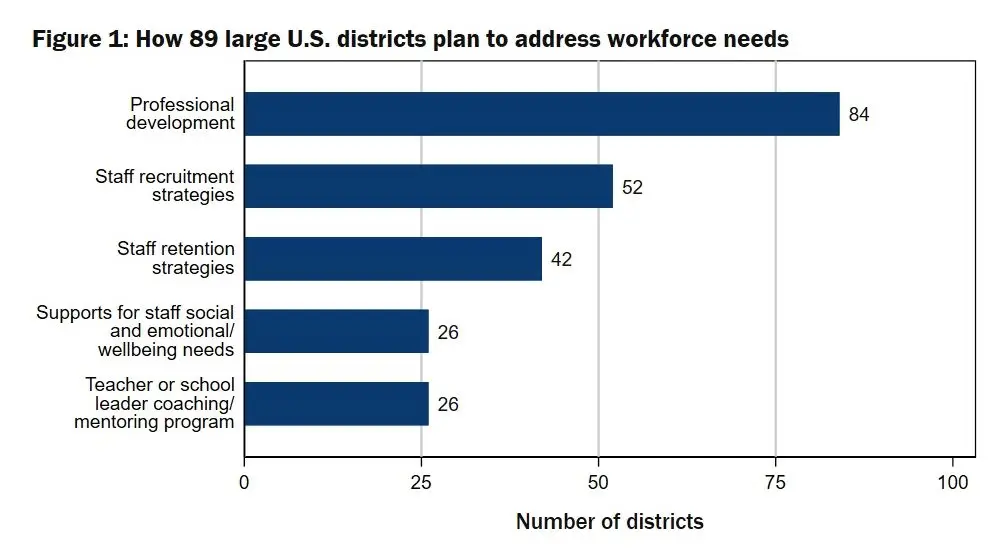

While nearly all districts said they planned to expand professional development, 44 plan to specifically train staff to better support students academically, according to our review. For example, Bridgeport Public Schools in Connecticut plans to help teachers learn how to identify and support students struggling in core academic classes. Twenty-one districts plan to train staff to better focus on students’ emotional well-being and their social needs; many are combining that with training on academic supports. The remaining 19 districts reference other types of professional development (for example, on health and safety protocols) or did not provide additional details.

Some districts plan to beef up staff recruitment

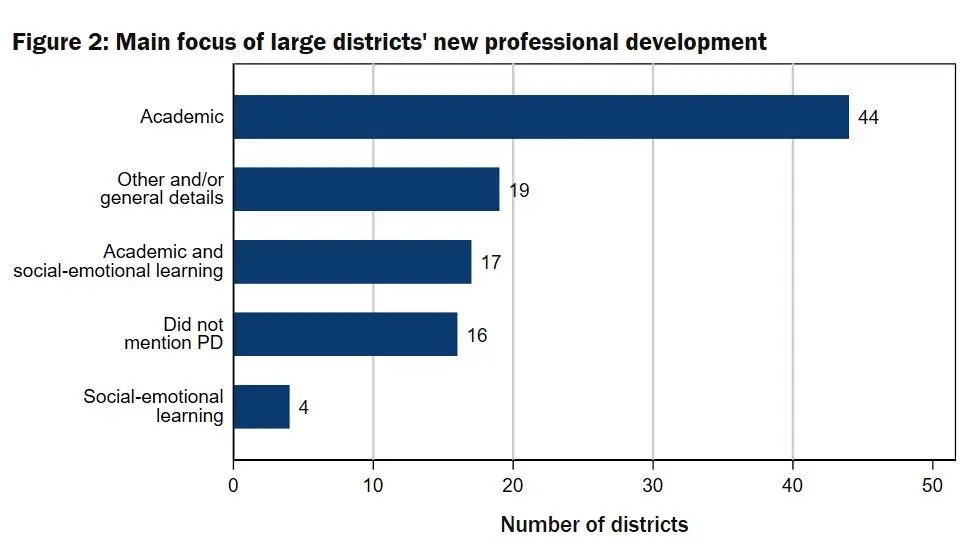

Of the 52 districts planning to spend federal relief money on staff recruitment, 37 plan to create or expand “grow-your-own” pipeline partnerships with local universities to train or certify new staff.

Districts’ investments in pipeline programs and partnerships include programs that target hard-to-staff teaching positions or make the certification process more attractive to diverse candidates. For example, Indianapolis Public Schools launched a new teacher residency program that offers an affordable path to certification for aspiring teachers.

Seventeen large districts are offering bonuses and incentives to new hires. Milwaukee Public Schools in Wisconsin, for example, plans to offer a tuition reimbursement incentive for newly hired nurses who make a three-year commitment to the district.

Eight districts plan to fund new recruitment efforts. In Arizona, for example, Mesa Public Schools plans to invest in a mobile recruitment lab to ensure potential new hires have transportation to work. Henry County Schools in Georgia implemented a new virtual recruitment process, which yielded over 300 new applicants for the 2021-2022 school year.

Three districts report relaxing job requirements in order to deepen the pool of qualified candidates. The Hawaii Department of Education, for example, lowered the minimum qualification for substitute teachers from a bachelor’s degree to a high school diploma.

New strategies aimed at retaining current teachers

Of the 42 districts planning strategies to retain current staff, 31 said they planned to offer one-time bonuses or salary increases.

A few districts planned other initiatives and programs to support current teachers. Twenty-six districts mentioned plans to support staff members’ well-being, perhaps in response to widespread reports of teacher burnout and exhaustion last school year. For example, Orange County Public Schools in Florida reported giving employees opportunities to take yoga and stress-relief classes. A quarter of districts (26) plan to provide mentoring programs to teachers or school leaders. For example, Guilford County Schools in North Carolina plans to fund mentoring and coaching for 350 new teachers, 128 school-based administrators, and 20 new principals.

Are districts’ plans enough?

Although it’s too soon to tell the full extent of any national teacher shortage in 2022-2023, it’s clear the profession is facing turmoil. Enrollment in teacher preparation programs is declining nationwide, and teachers report higher levels of stress and lower wages compared to similarly educated professionals in other sectors. Offering one-time bonuses to retain current staff isn’t a long-term solution for addressing these problems, but it may be a good move considering district leaders must spend their federal relief dollars by 2024.

By far, however, large and urban districts in our sample said they’re increasing professional development to support staff. But professional development can vary widely, and research shows it has not consistently improved teacher practice or boosted student achievement. For the long term, districts could consider other strategies to attract and retain teachers, including:

Reimagine teachers’ roles. In Arizona, Mesa Public Schools, the state’s largest district, is addressing educator shortages by moving away from the “one teacher, one classroom” model and instead having teachers work in coordinated teams of specialists. The idea is to share the load among working professionals, which could make the industry more appealing for current and aspiring teachers. Arizona State University’s teachers college is supporting the effort and now partnering with the School Superintendents’ Association to meet growing national interest in the approach.

Further support staff’s mental health and well-being. Only 26 large districts in our sample said they planned to put more funding toward supporting staff’s mental health and well-being. That means about three quarters of large districts may not be investing in these strategies. The need is clear: about 20 percent of principals and 35 percent of teachers say they don’t have access to employer-provided mental health support, according to a recent survey conducted by RAND.

Empower and develop younger staff. Education scholars featured on the Brown Center Chalkboard have said strengthening teacher preparation programs is one major way to address teacher shortages. Better mentoring could be part of that; first-year teachers paired with mentors were more likely to return for a second year, one federal study showed. Meanwhile, the U.S. Department of Education and the Department of Labor recently announced plans for a registered apprenticeship program for teaching. The program aims to support states and other partners to create affordable pathways for teacher-trainees—including those who already work in districts—to gain teaching experience and take coursework under the supervision of a mentor teacher. Similarly, Tennessee has used some of its federal pandemic relief funds to launch a teacher apprenticeship and scale residency and “grow-your-own” programs.

As school districts continue addressing pandemic-related learning losses, they will need to think bigger and more long-term to tackle the root of long-standing staffing challenges. But for leaders to reimagine their workforce, they’ll need continued support from state and federal policymakers. That support could make room for districts to explore new approaches to staffing, such as redefining job duties and teacher role requirements, helping under-skilled workers enter the profession, or even boosting salaries to compete with higher-paying industries. Doing so will ensure their staff is more resilient and prepared for future crises and ready to help students recover from pandemic losses.