This article originally ran in the November 2010 edition of the Phi Delta Kappan. We’re republishing it here because many of the ideas it describes are now being tested in real time on a large scale, as school systems across the country experiment with new structures that allow them to support remote learning.

Critics of U.S. K-12 education often complain that the basic structure of public schools hasn’t changed in a hundred years. That criticism doesn’t fit the facts today — there are many exceptions to the generalization that all instruction is delivered by a lone teacher in a sealed-off classroom — and it will be more dramatically wrong in the future.

Over the next few decades, public schooling will evolve and diversify much further. Though many children will continue to attend conventional schools, an increasing number of children will attend schools that deliver instruction, use time, and define the work of teachers and students very differently. Moreover, the idea that a school’s primary identity is linked to the building that it and it alone occupies is already an anachronism.

In the past, public schools were buildings where students were housed from 8 a.m. to 3 p.m. In the future, public schools will become a broad and diverse mechanism for helping young people access, master, and use information. This change will be as radical as what has happened to public libraries over the past 30 years: Originally, public libraries were the physical buildings where people went to gather information. Now, the process of information gathering is diffuse, infinite, and without any physical home; it is managed entirely by the user and not the physical provider. The notion that in the year 2040, all American 12-year-olds will be boarding a school bus and riding to a comprehensive public school building to learn how to read and write from 8 a.m. to 3 p.m. is now as preposterous as presuming that in the year 2040 that same student would be riding a bus to the public library to flip through the card catalog for books on snakes.

Schooling alternatives are emerging or will soon emerge, and new approaches to government funding and oversight are also likely to emerge as public education diversifies.

The new landscape of public schooling

In the future, large numbers of children, up to half of those whose education is paid for with government funds, could attend schools that differ from the dominant model in which students and career teachers are in all-day contact with one another and in which teachers are fully responsible for assigning, explaining, and enriching the materials to be learned; assessing students’ learning; and remedying deficiencies.

New forms of education are emerging for four reasons. First, the explosion of technology: Entrepreneurs and technology developers are experimenting with new forms of instruction that provide high-quality content with ongoing support for students at reduced costs.

Second, recession: States and localities, faced with severe revenue declines, are searching for ways to make the best use of their costliest and scarcest asset, excellent teachers. If current cutback scenarios continue (pink-slipping large numbers of junior teachers in order to maintain salaries for smaller numbers of senior teachers), many districts will find themselves with too few teachers to provide all the needed instruction and will look to technology for ways to increase the numbers of students one person can teach.

Third, public sector innovation: Districts such as New York City and Denver are searching for forms of schooling that might be more effective with groups that now experience low rates of success, and they’re developing accountability systems based on school performance, allowing much more flexible use of public funds. New York is also formally experimenting with combinations of online and face-to-face instruction and intends to expand the number of schools making new uses of teachers, technology, time, and student work.

Fourth, a new commitment to attaining standards: This national focus on learning outcomes has changed the entire sector from one focused on how and where students learn to a system focused on what they learn.

Now, when a policy maker, superintendent, or academic is confronted with a novel school concept, the question is no longer whether this model allows students to meet certain seat-time requirements or ensures that teachers are qualified or guarantees that students have a sports program. The first and only question is: Does this model help students meet standards?

At least three new forms of schooling are likely to become common enough to be recognized by teachers and parents as “normal.”

- Virtual schools in which teachers’ sole contact with students is by monitoring progress on technology-based courses, assigning technology-based remedial and enrichment materials, assessing, and grading.

- Hybrid schools that mix full-time teachers, contractors, and technology-driven instruction. Students learn at the school building and in other places. Full-time teachers manage online learning by monitoring an individual student’s progress, assigning remedial work whenever a student falls behind, assigning enrichment materials and paper writing, and convening discussion groups. Students have some combination of virtual and face-to-face support, some from licensed teachers, some from subject-matter experts who aren’t certified teachers, and some from tutors or paraprofessionals.

- Schools that operate as brokers of instructional services, providing some courses by hiring contractors instead of unionized classroom teachers. For example, a school may contract with hourly rate music teachers who already work in the community or firms that provide classes in the hard sciences and advanced math (taught by advanced graduate students or people working in industry); or they may partner with community college or university teachers to provide instruction under pay-per-course arrangements.

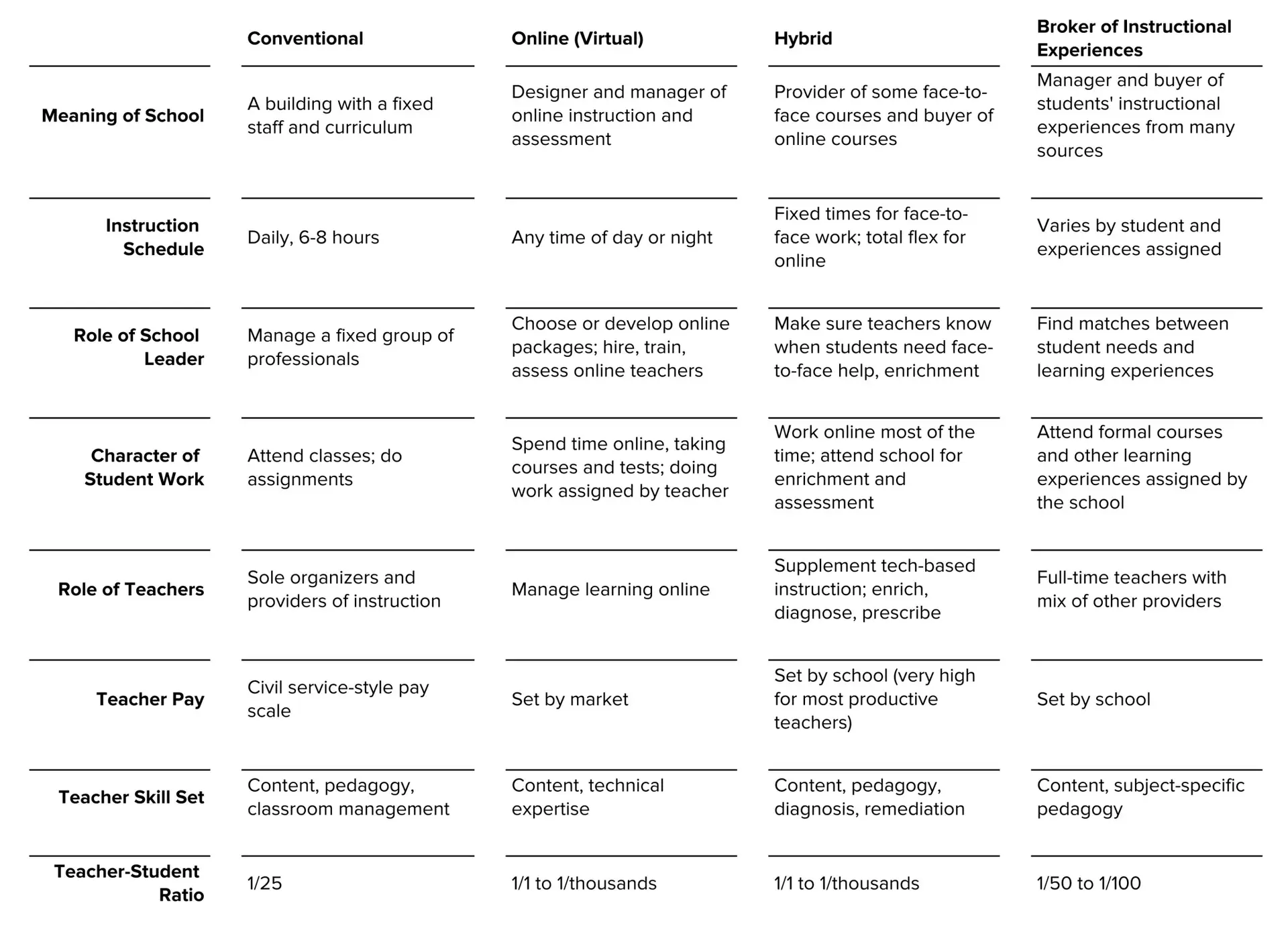

These different forms of schooling each have different implications for the use of time and the day-to-day work of school administrators, teachers, and students. Table 1 analyzes these implications in detail.

Table 1. Future Forms of Public Education

These alternatives aren’t common now, but examples of them exist. Several states have online schools, and many states accept credits from a national vendor (K-12). Many school districts offer assessment and enrichment courses for students who take most of their instruction online. A new charter school operator, Rocketship, is committed to using technology-based methods to individualize instruction and focus teachers’ work on what only they can do. These are the first examples of “hybrid” schools and are prevalent by necessity in some rural districts where online courses are the only way students can access foreign language or upper-level math and science courses.

“Broker” schools are also emerging, though mostly at the secondary level. New York City has led the way in developing “multiple pathways to graduation,” which include schools that assign students to learning alternatives, both inside and outside the school building, depending on students’ learning needs and their schedules.

The fact that these alternative approaches to schooling exist now doesn’t mean they’ll become prevalent. Most parents will continue to want their children supervised and mentored by adults and like the social interaction that comes from the traditional school structure, so the demand for purely online schools will be limited. However, hybrid and broker schools, which offer flexibility and individualization yet can maintain close contact between students and professional adults, could appeal to parents who think their children could benefit from both individualization and direct adult oversight. They could also appeal to districts that need to find ways to serve students who can’t or won’t journey to school every day or to maintain quality course offerings on a shrinking budget.

How common will these schools be?

Whether these new forms of schooling become common or remain rare depends in part on their performance and in part on the removal of regulatory and funding barriers. In an era of performance accountability, districts or charter operators are unlikely to adopt new approaches to schooling if they’re not, at least for some students and compared to conventional schools, effectiveness-neutral. One important dimension of effectiveness is citizenship preparation. Though parochial, private, and charter schools are generally as likely as public schools to produce students who endorse First Amendment principles and vote (Campbell 2006), there can be exceptions, and the results for virtual schools are not known.

Labor contracts and teacher licensing rules privilege individuals with skills and training needed by conventional schools and complicate the hiring of people with skills needed by different forms of schooling.

Full exploitation of technology in hybrid and broker schools won’t just happen. In theory (though not yet in fact) it should be possible to build schools around new integrated instructional systems that combine adult and student work with technology to cover whole subjects or entire school curricula. Integrated instructional systems for hybrid and broker schools would merge individually paced presentation of material with teacher work, that is, diagnosis, enrichment, and leadership of group interactions. Most material would be presented individually to students by technical means, but teachers would track students’ work and intervene when needed. Consistent with the design of the instructional system, teachers also could suggest enrichment work, assign projects, lead discussions, and present materials not covered by technical means.

New integrated instructional systems would redefine teaching. Significant components of instructional delivery, assessment of results, and feedback on performance could be done with technology, offering students more individualization than is possible under the current classroom structure. The teacher would rely on technology to organize and deliver routine instruction whenever possible and reserve his own time and attention for intervention that only an expert human can do, for example, to explain an idea in a way not provided by the text or digital materials, intervene with an individual student, frame group work, or call attention to productive differences in ways different students approach a task. This also creates a new role in the teaching space for an adult who can help students navigate the technological supports, a role that might need different combinations of skills than do current teacher duties.

Integrated instructional systems would also transform teacher preparation. Teachers would need to interpret assessments, know what technology-based supplementary resources were available and what they were good for, and decide when to use supplementary resources and when to provide personal tutoring or coaching. If students are to benefit from teacher use of supplementary technologies, teachers must be clear about their instructional objectives and understand what resources are most useful as remedies to particular student performance problems.

There’s no guarantee that any new form of schooling will be particularly efficient or meet the needs of students for whom it’s designed. States and local school districts should closely track the performance of these schools, as we will suggest below.

Public regulation and oversight

Though there are existing examples for all these kinds of schools, the virtual, hybrid, and broker models all strain against the current structure of funding mechanisms, regulations, labor contracts, and accountability systems.

All, for example, require much more flexible use of money than state funding programs allow. Schools need cash — not people and resources purchased elsewhere and allocated to them — so they can buy services and products and pay for nontraditional teachers working part time or under contract.

Current state or local requirements that set class sizes, require that funds be used only to pay salaries, mandate hours of school operation, or set minimums for student seat time all militate against these new forms of instruction. Similarly, labor contracts and teacher licensing rules privilege individuals with skills and training needed by conventional schools and complicate the hiring of people with skills needed by different forms of schooling. We could envision a system where money not only follows the child in a pure form of student-based budgeting, but where even the dollars allocated to an individual child are broken up by standards, so that a given unit of information the state owed to an individual child has a specific price tag. This would empower the school or family to contract with multiple providers for different components of a child’s education.

The existing virtual, hybrid, and broker schools almost all rely on special exemptions or alternative regulatory mechanisms that are by design limited to a few instances. In many states, virtual schools are often funded from separate and strictly limited state appropriations. When students transfer to virtual schools, state dollars held by school districts (and the regulations that accompany them) do not move. Similarly, hybrid and broker schools are often based on charters, which allow novel approaches to hiring and funds use but are limited in number by state-legislated “caps.” Charters and virtual schools are also generally exempt from collective bargaining agreements that limit hiring, teacher work assignment, and pay scales that base compensation on seniority.

There are, however, emerging opportunities for broader experimentation with new forms of schooling. The states of New York, Louisiana, Colorado, Illinois, California, Pennsylvania, and Connecticut have allowed their largest urban districts to develop new schools and attract new independent school providers.In New York, the United Federation of Teachers has cooperated with the city school district’s experimentation with new schools, and the union is itself running some modestly innovative charter schools.

The districts thus empowered are experimenting with both new forms of schooling and new institutions to support school quality. For example, teacher training and school improvement efforts in New York City are no longer constrained by the capacities of the district central office. Schools can choose among dozens of sources, including some staffed by district employees and others run by nonprofits.

Nationally and in key cities (New York, New Orleans), new charter management organizations (CMOs) are being formed to develop distinctive approaches to schooling and reproduce these at scale. As these organizations develop, creating additional schools of the new kinds will be easier, both in the cities where they first developed and elsewhere.

Other states (Wisconsin, Minnesota, Ohio, and Indiana) might follow suit, either putting schools under state or mayoral control or exempting specific localities from key regulations. As these governance reforms spread among districts and states, new forms of schooling are likely also to spread.

Virtual schools also have appeal outside major cities, especially in remote areas where students might not be able to get to school every day or in small districts that can’t find qualified instructors in key subjects such as science and mathematics. Virtual schooling materials developed for rural and small town use might also be adapted for city schools and vice versa, thus accelerating the spread of new forms of schooling everywhere.

New forms of schooling might also prosper under a voucher system that welcomes almost any private or public entity to open a school and allows families to choose almost any instructional program. However, under those circumstances, cautious entrepreneurs might avoid highly innovative schools, preferring to reassure parents with familiar methods and assurances of conventional custodial arrangements. As long as entrepreneurs could fill their schools, they might not be concerned about students whose needs remain unmet.

On the other hand, school districts responsible for improving options for the most disadvantaged students might be more willing to take risks and develop multiple new options. Thus, a more conventional governance arrangement, under which a public agency is responsible to ensure that every student has a school, might lead to more development and experimentation with schooling options than would a wide-open voucher system. As long as high levels of accountability continue to require districts to help every student meet standards, and as long as open and competitive marketplaces exist where multiple providers can enter, we can expect that districts and families will continue to pursue innovative strategies that deliver results regardless of how that content is delivered or the physical structure of the building.

Conclusion

These diverse forms of schooling challenge the idea that the defining attributes of public education are uniformity and adherence to exhaustive rules. Standards-based reform encouraged some diversity of practice in pursuit of common student outcomes, but its early supporters scarcely imagined the diversity of approaches now emerging.

The new forms make it even more important for states and localities to determine what minimum skills all students need to attain and what, if any, common experiences they must all have. Their task is not easy: Prescription that is not based on evidence about what all children truly need will stifle innovation, yet too little clarity invites questions about what common interest schools serve.

States and school districts will also need to clarify how to measure student outcomes — including how tests will be combined with longer-term measures of student and school performance — and what will be done about schools, however defined, where students do not learn. Ducking these questions was easy when public education was defined in terms of the body of rules made over time to control it. New possibilities for diversification and individualization of instruction put new burdens on those who define the public purposes of education.