Earlier this month, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention made clear that good ventilation and consistent mask wearing are far more effective at preventing the spread of COVID-19 than disinfecting surfaces.

This clarification was long overdue. Scientists have long suspected that the virus is mainly airborne. They recognized that measures like deep cleaning and temperature checks were likely more effective as hygiene theater than as a strategy for actually limiting spread.

In the meantime, however, thousands of school districts across the country built enormously complex fall reopening plans with a full day for at-home learning, dedicated to student check-ins, teacher planning — and deep cleaning. The result is a modified four-day week with students receiving significantly less live instruction per week.

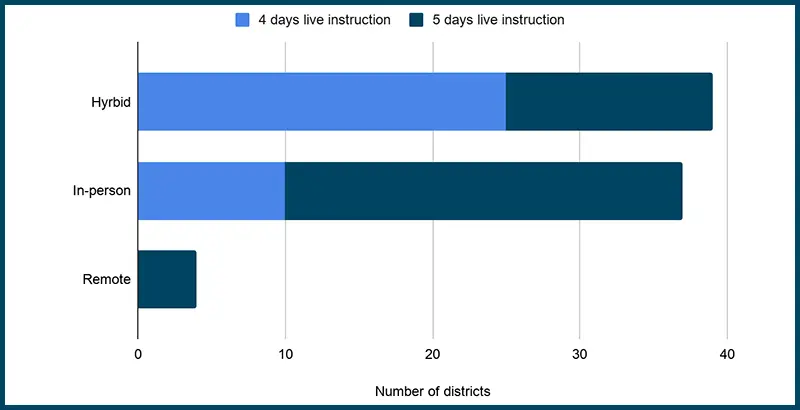

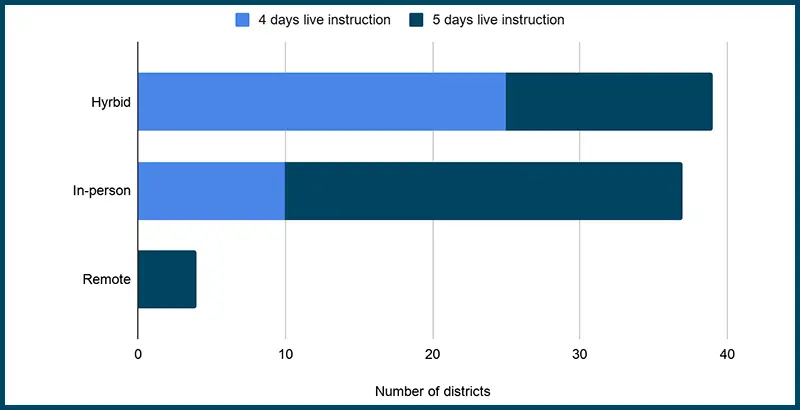

In New England, where the Center on Reinventing Public Education is conducting an implementation study of 81 district reopening plans, the four-day model is common. We found it in nearly two-thirds (25 of 39) of districts with a hybrid learning model and in more than a quarter (10 of 37) of districts that are providing in-person instruction. One-third offered five days of live instruction to all students, with no time off for cleaning.

Eliminating a full day of in-person instruction was always a high-cost strategy from an education standpoint. And now we have confirmation that it’s unnecessary — except when there are active COVID-19 cases — to protect students’ and educators’ safety.

Interviews we’ve conducted with teachers, students and families reveal some of the educational costs. In the New England schools we studied, leaders often did a poor job of setting clear expectations for student learning on the at-home day. We know from past research on four-day school weeks that without firm leadership and strategic planning, districts struggle to maintain interventions and enrichment activities they had initially intended for the fifth day.

The result, too often, is that little meaningful student work is done on “remote Wednesdays” unless students initiate it. In effect, “remote Wednesdays” sometimes end up as little more than a day off for students — and an extra day of planning for teachers.

A small but vocal group of teachers we interviewed said the at-home day is a central reason that kids are learning less this year. “I don’t give them assignments on Wednesdays anymore because students weren’t doing the work,” one high school science teacher told us. “I want to try to be more understanding of their home lives right now, but it makes me feel like an awful teacher because they should be learning and I should be teaching.” The teacher said attempts to use the day for scheduled check-ins also failed: Students showed up for their appointments only a quarter of the time.

Of course, there have been some advantages to the four-day week, given the unique challenges of teaching and learning in a pandemic. Schools report that some students use the time for employment. One teacher told us, “Because of the community we live in, a lot of students feel the need to hold jobs and a lot of them will pick up an extra shift at work on Wednesday.” Other students like having the time to catch up on work. One school in New England used the time to sustain student clubs and extracurricular activities, making it possible to maintain valued social time with peers.

Many teachers also report that they appreciate having more time for collaboration and planning in an extraordinary year. Some use the time to identify students who are struggling academically and emotionally, and to strategize how to support, engage or motivate them. One teacher at a small, rural school said the additional planning time allowed her and her colleagues to work collectively to design support plans and structures: “This year, we meet two hours a week [on Wednesday]. We pick a grade, and we talk about every student in that grade level — how they are doing in all of their classes and what additional action plan steps might need to be put in place next. . . . Last year we didn’t have that same collaboration time.”

While a full day of at-home learning may have been considered necessary this year and even shown some benefits, it has come at the expense of essential academic progress and socialization time for students. For the vast majority of schools, the idea has outlived its usefulness. Yet there is real danger that school systems and teachers are getting attached to the four-day week and may lobby to retain the schedule next school year, even after students are largely vaccinated. This would be a mistake.

Instead, schools should consider what they gained from having a fifth day — time for tutoring, intervention and teacher planning — and build that into the regular school schedule. For example, Pride Prep, a charter school in Spokane, Washington, has maintained a five-day schedule this year but ensured that teachers have time for data-driven planning every week. Students can attend dedicated class periods for small-group intervention and acceleration.

Districts considering carrying the four-day week into next year must ask themselves hard questions about how it will benefit students. There are some defensible reasons, and models. Durango School District in Colorado, for instance, shifted to four days but used the time to offer students extended internships and increase the number of high schoolers taking classes at the local community college.

The abbreviated school week can no longer be justified by a desire for flexibility — or precautionary deep-cleaning efforts — alone.

As soon as possible, we should strive to get all kids back into buildings five days a week, if only to give them structure and focus. An enormous amount of work awaits as we begin to repay students for months of lost school time and address their unprecedented social-emotional needs and academic gaps.

We cannot afford to throw away an entire day of learning and student support based on a false scientific premise.

The post was originally published in The 74.