This commentary is a response to the Center on Reinventing Public Education’s State of the American Student project, an effort launched in fall 2022 to track and report on pandemic recovery and school reimagining efforts over the next five years.

In a new collection of essays about improving American education published by Opportunity America, CRPE Director Robin Lake argues that building a more nimble and equitable school system in the wake of the pandemic requires a new coalition of parents and teachers who can link arms and fight for key needs. This excerpt highlights the six most crucial needs. You can find Lake’s full essay in Opportunity America’s new report Unlocking the Future: Toward a new reform agenda for K-12 education.

Reformers’ core tenets—choice, accountability and teacher quality—will be as essential as ever in the post-pandemic era, but we’ll need to see them in new light as we respond to a changing world. A compelling new agenda must recognize the imperative for a more customized, agile public education system. And it must appeal to what families and educators truly want and need.

The pandemic years highlighted six core needs popular with families and educators and worth fighting for.

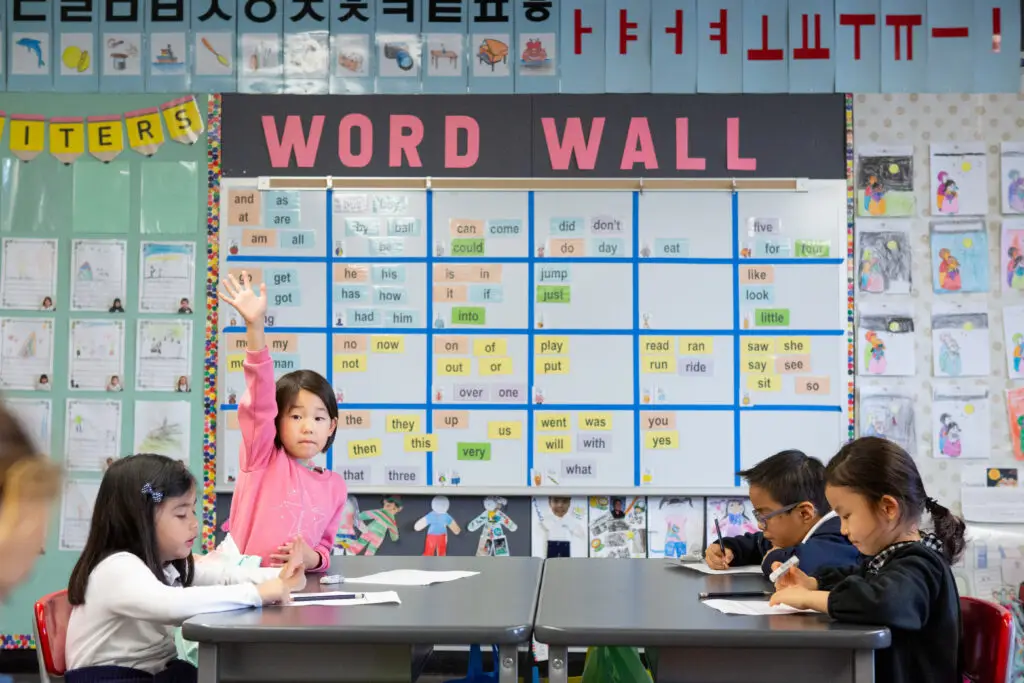

1. Highly individualized school designs. Kids have always had widely varying talents and academic competencies. But the educational response to the pandemic exacerbated these differences and revealed how badly designed most schools are to meet diverse student needs.

Why can’t schools be more customized, focused on early intervention and designed to cultivate students’ individual interests and talents? Schools should do what is required to serve the extremes, not the mean, capturing talents that are now being lost and motivating students who are settling for mediocrity. This might mean that some schools’ primary role would be to curate services and supports rather than trying to provide everything to every student. Choice, accountability and teacher quality will be as essential as ever, but we’ll need to see them in new light.

2. A reimagined teacher workforce. Diverse needs demand diverse solutions. Schooling can no longer take a one-size-fits-all approach—and moving toward more flexibility will require widespread innovation and adaptation.

Technological tools have a role to play, but the most important solution is an old-fashioned one: stronger relationships between adults and students. Classes based on a ratio of one teacher for every 30 students no longer work. The future demands more creative staffing and school models that are more effective for both adults and students.

We need a wider variety of teachers. Some will invariably be specialists who are experts at teaching specific bodies of knowledge. But others should focus on building relationships with students and curating customized learning packages. A broader conception of the teaching profession could also encompass community educators of the kind that emerged during the pandemic to tutor and mentor students.

Reforms of this kind can improve teacher satisfaction and create more opportunities for individualized instruction. Surely, this is something around which Republicans and Democrats can come together.

3. Happier learning environments. Many students’ and teachers’ emotional and mental health suffered during the pandemic. But this wasn’t new. The pandemic simply revealed how badly equipped schools are to address those needs and how schools indeed often exacerbate them.

Left to their own devices while schools remained closed, parents and educators formed pods and microschools. They homeschooled their children and used online tools in creative ways. They let antsy young children run around when they needed to and allowed older students more control over their learning and schedules, crafting instruction to meet each student’s particular needs.

Families of color reported that their children excelled academically and grew in confidence when they were taught in racially affirming environments. Teachers reported higher levels of satisfaction. Parents reported that their students were more likely to feel known, heard and valued and were more engaged in learning.

4. Career-relevant learning. The world of work and the global economy are changing. The future demands more problem solvers, creative thinkers and people who know how to collaborate. But our schools are ill-equipped to help students develop these strengths.

During the pandemic, high school students made clear that they found school boring and irrelevant without other kids or extracurricular activities. Many who dropped out in the past three years now say they are increasingly dubious about the value of high school and even college.

There is an urgent need to reshape high school to better prepare students for careers, including with apprenticeship programs and instruction leading to alternative credentials. Schools can start by forming creative partnerships with higher education and industry to help students develop their passions and realize their dreams.

Reforms of this kind will require new thinking about accountability and graduation requirements. Schools for younger students should focus more closely on a limited set of core requirements, perhaps just developmental skills directly linked to readiness for secondary education. Older students should be able to build personalized learning pathways, earning competency-based credits that count toward high school graduation, college coursework and industry credentials.

5. Families and communities as true partners. The pandemic forced families and communities across the country to experiment with learning environments. When kids were learning from their living rooms, schools had no choice but to treat parents as full partners in the learning process. Some parents took matters into their own hands, forming learning pods in which teachers reported more flexibility to tailor learning experiences to student needs. Community organizations such as afterschool providers also formed pods, bringing a new and more diverse group of educators to the fore.

Parents and community leaders sometimes found they were more effective in the classroom than the child’s regular teacher. And students of color formed new connections with caring adults who looked like them and shared their life experiences. These parents and children are unlikely to want to relinquish the magic they uncovered amid the gloom of the pandemic.

It’s time to reimagine parent information systems, design schools that leverage community expertise and empower families to meet students’ needs when their neighborhood schools fall short. It’s time to ask schools to work more closely with others in their communities, including businesses, hospitals and clinics, social service organizations, cultural institutions and colleges.

Equity gaps must be prioritized, not swept under the rug. Community “navigators” and community organizations are well positioned to help. But proposed solutions must be evaluated by diverse points of view and operated by local communities.

6. A more agile and resilient public education system. Families, local businesses and civic leaders have seen firsthand that the institutions charged with educating children are in crisis. K–12 leaders already know this. Students’ academic challenges, teacher shortages and morale problems, classroom behavior issues and raucous board meetings are causing more and more superintendents to consider quitting.

And things will only get tougher from here. A painful fiscal reckoning looms, as declining student enrollment threatens to exacerbate the end of supplemental pandemic-era education funding.

Agility and responsiveness will not emerge out of nowhere. We need more relaxed state requirements, more philanthropic investment in innovative staffing and instructional models and allowances to revisit burdensome labor agreements when necessary. We also need better crisis management to prepare for natural disasters, future pandemics and other disruptions.

Funding should increase. It should be more flexible and follow students for longer. A student who graduates early should be able to use saved funds to come back to school for additional learning later in life. A student who develops a passion for dance should be able to pay for specialized dance classes by forgoing another elective. Government can play a critical role, providing oversight, informing parents and protecting students. But it doesn’t always need to be the main provider of services.

Getting from here to there

Moving toward a bold vision for the future of learning will take a commitment to innovation, policy change and focused advocacy. The education reform movement must admit mistakes and let go of old ways. We need a new coalition with fresh ideas that is also clear-eyed about what it will take to bring about the change it proposes. We all must be willing to learn the lessons of the past, and we must commit to engaging with people who have disparate points of view in service of a common goal.

If we care about preparing every student for a life of informed citizenship and economic independence, we cannot afford infighting and petty squabbles. Supporters from all corners must come together to ensure society does not squander the talents of a generation.