More school systems have welcomed students back to campuses since school started. But rising COVID-19 case counts have stalled other districts’ plans to reopen their buildings, and other questions have begun to mount. Will they be able to re-engage students who struggle to connect to school? Are they ready to measure and address learning loss, too? Are they ready to go back online if they must?

The latest update of our analysis of 100 of the nation’s highest-profile school systems suggests districts have been adapting as they go, but there is much work ahead.

And it underscores the importance of providing clear public health guidelines that help school district leaders move beyond the challenge of reopening logistics to focus on re-engaging students and addressing learning loss—something the incoming Biden-Harris Administration has already signalled is a priority.

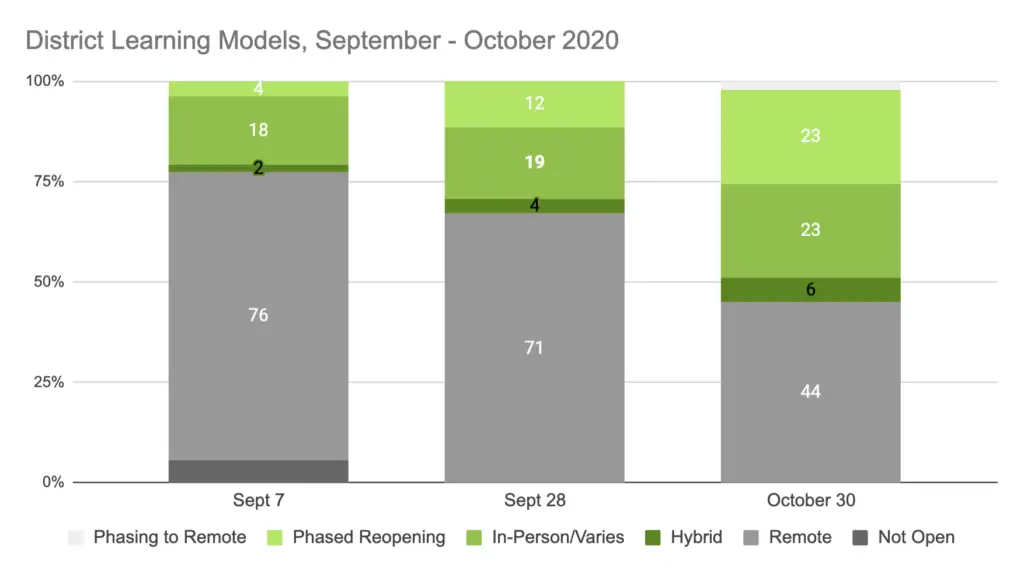

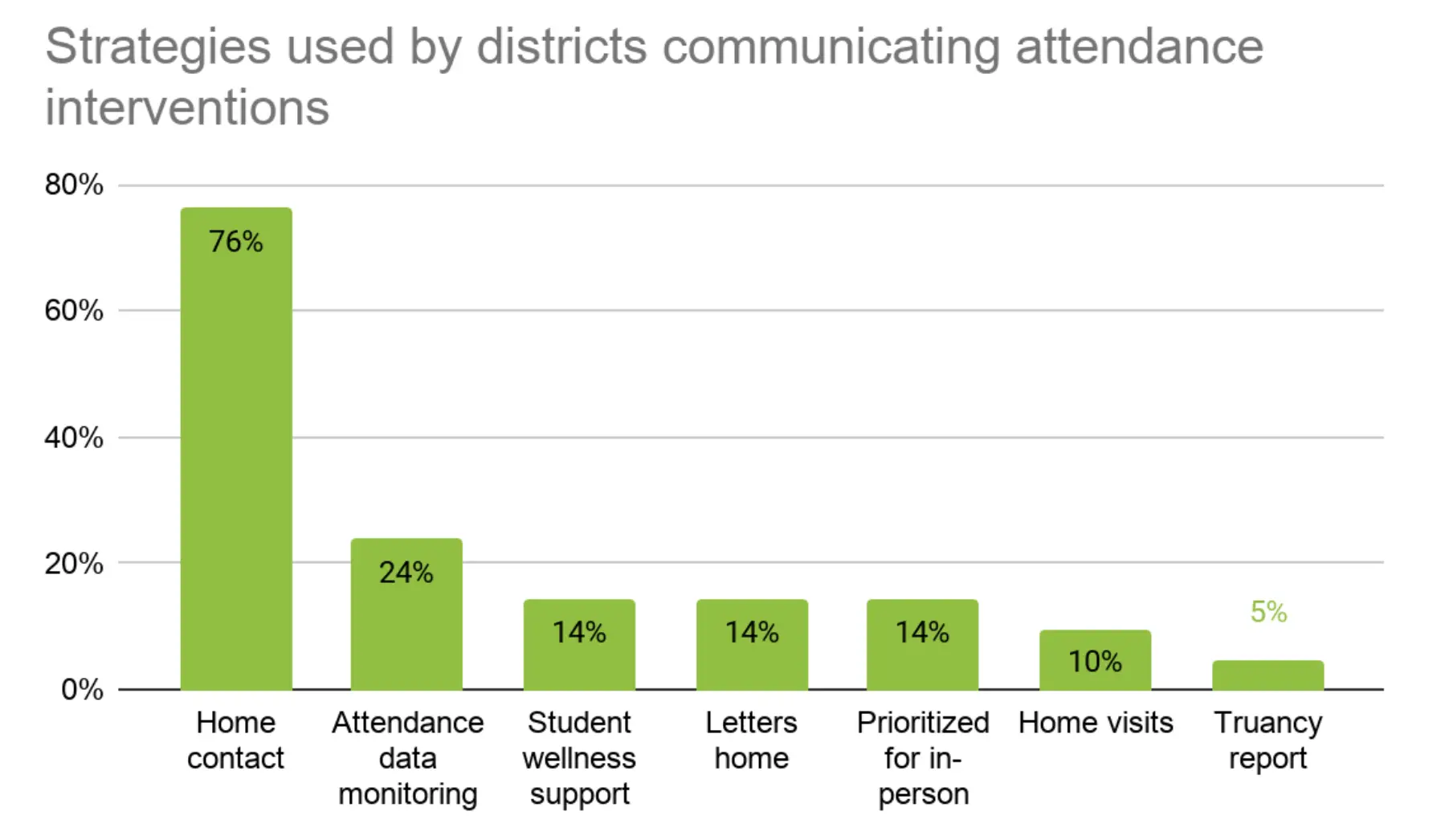

More districts are welcoming students back to campus—but remote instruction is not going away

In September nearly three-quarters of school districts we reviewed were teaching students remotely. Now fewer than half are fully remote.

However, this trend has already begun to stall. Escalating national virus rates have forced districts in large cities such as Atlanta, Boston, and Denver to push back plans to reopen school buildings—once again raising the specter that a churn of shifting reopening plans will detract leaders’ focus from academics.

While districts are shifting between learning models, remote learning is not going away. Districts in hybrid and fully in-person models still face a sizable population of students preferring to stay remote. And remote learning is undoubtedly impacting the quality of instruction and students’ engagement levels. Not all districts have the resources to provide devices for all students, and adequate internet connectivity remains an issue. Districts attempting a return to hybrid or in-person learning will have to allocate more resources to health and safety measures that could have been used to strengthen technology access gaps. These are challenging trade- offs to navigate.

This prompts the question of whether districts are able to ensure high-quality remote teaching and learning for all students as they navigate these shifts.

Reduced instructional time, coupled with spring learning loss and continued gaps in student access and engagement, will force schools to rethink their priorities. Every district must communicate a clear vision of what students will experience as learners this year, how they will decide, and who will get a say.

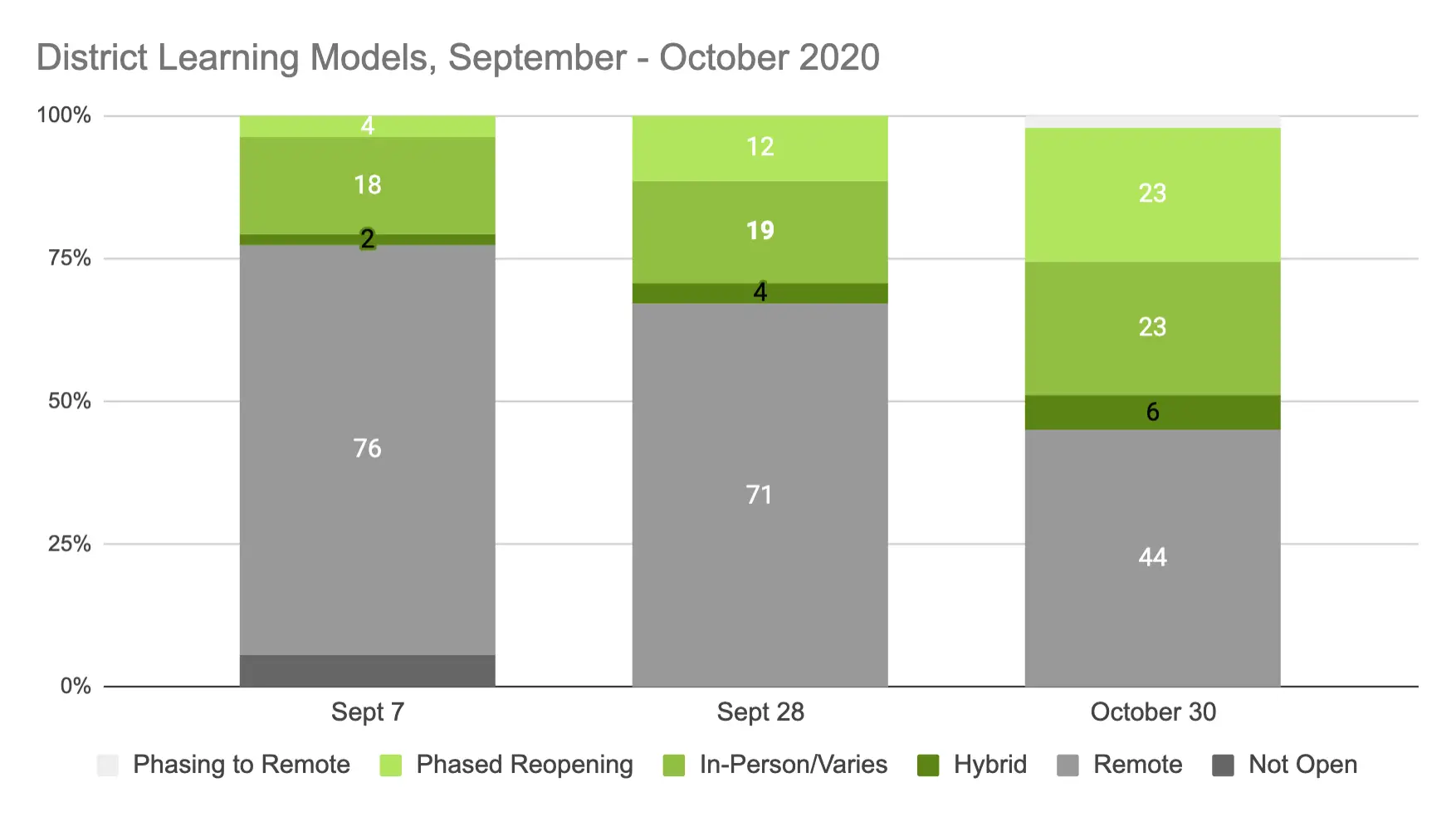

Assessments are commonplace; comprehensive plans to address learning loss are not

Most districts in our review (80 out of 100) say they have plans to measure student learning, and nearly two-thirds specify strategies like tutoring or small-group instruction for students who fall behind.

But many districts do not provide specifics about what assessment system they’ll use or what data they will make available to parents and the public. Of the 100 districts reviewed, 16 describe will use a universal, standardized diagnostic (like i-Ready or NWEA’s Measures of Academic Progress), and 5 will use an internal district diagnostic assessment. The remaining 59 districts that plan to use assessments don’t provide details.

Districts’ choice of assessment tools can be critical. A universal test allows leaders to assess student learning needs across schools, and it helps districts strategically allocate resources (like tutors or extended learning time) to schools where students need the most help. Relying on assessments tied to specific curricula instead of common standards, or created by individual educators, won’t help leaders make these crucial system-level decisions.

In addition, districts should share whatever student assessment results they can with parents and guardians, as frequently as they can. Parents’ new role as learning guardians during remote learning requires them to know their children’s learning gaps and needs—just like teachers. Researchers relying on the disruptions of schooling from past disasters have published dire predictions about the toll this pandemic could take on student learning, but most communities are still in the dark on how it has affected their children.

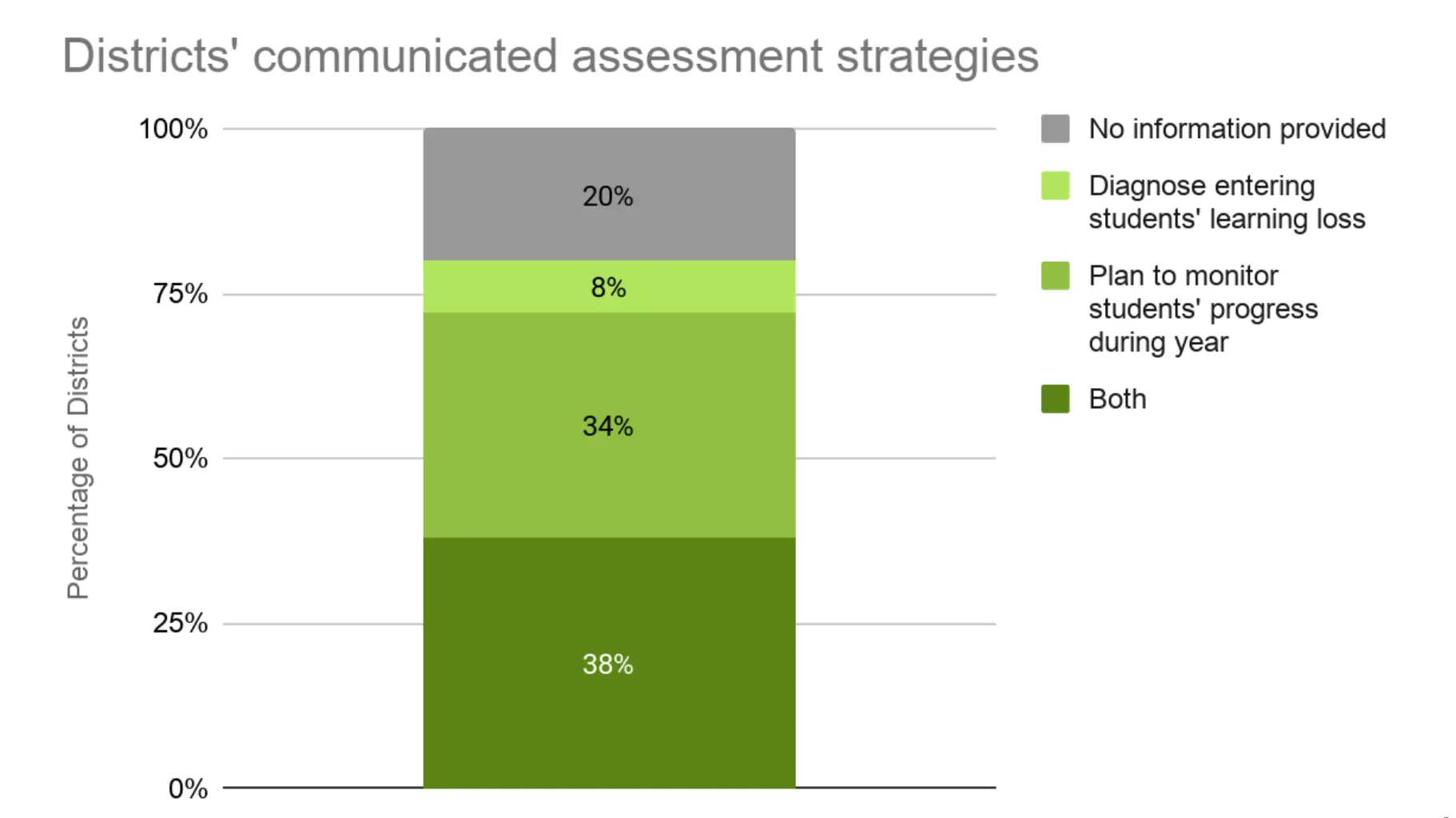

Where are the children? Few districts share plans to answer this question

Just over one-fifth (21) of the districts in our analysis explain how they are identifying high-absence students and getting them to participate in remote learning or return to school. The most common intervention is frequent calls to students’ homes. Three in four districts that publish plans indicate they’re using this tactic.

More districts are likely making efforts to track down missing students that they aren’t describing publicly. But falling enrollment and attendance could cost schools critical funding and exacerbate the pandemic’s already staggering toll on student learning.

A few districts stand out with their proactive efforts. Atlanta Public Schools consistently monitors student logins and attendance, and developed a plan to escalate communication with families of disengaged students. Schools send home “no contact letters,” similar to the attendance letters they would send home under normal conditions. When students are not logged on or do not remain online throughout the school day, staff make daily phone calls directly to their parents or guardians. When students have not logged in over a three-to-four-day period of time, or staff are unable to contact their family, staff visit them at home.

Maryland’s Prince George’s County Public Schools communicates a commitment to ensuring that 100 percent of its enrolled students participate in remote learning, and deploys nonprofit partner organizations, community school coordinators, and other staff to orchestrate phone calls and virtual home visits, phone calls.

Large districts highlight big systemic problems

These newest findings show how school districts are too often consumed by crisis response and the logistical challenges of reopening to develop new strategies for teaching and learning. They must focus on finding new ways to re-engage missing students, identify learning needs, and then address learning needs.

It underscores the importance of the new Biden-Harris administration’s efforts to fill the leadership vacuum that has hampered school districts’ response to the virus. Districts are going it alone—procuring equipment and setting up plans to keep children safe in buildings, only to have those plans derailed by rising case counts in their communities.

Large numbers of students remain disengaged from learning or going without crucial support services, and it’s become increasingly clear that many school systems cannot simply rely on a return to school buildings to solve this problem.

At every stage, school districts’ response to the pandemic has been thrown off course by the mistaken assumption that things will soon return to normal.

Spring was lost when the pandemic caught everyone by surprise. Summer was wasted as many of the nation’s largest school systems were forced to abandon or delay plans for in-person learning. Now schools are nearing the end of their first semester, still grappling with public health challenges and unable to focus fully on student learning.

Providing clearer public-health guidance is a vital first step, but the new administration’s efforts should not end there. It should also push states to take a more assertive role, setting clear expectations for student learning and providing more support to districts’ efforts to engage students and address learning loss.