From California to West Virginia, teachers unions have squared off with charter school supporters in fights framed as fundamental struggles over the future of public education.

Meanwhile, some charter school teachers have launched unprecedented strikes of their own—and sometimes drawn shows of solidarity from leaders of teachers unions.

Unionized charter school teachers complicate the usual “us vs. them” narrative. But debates suffer from a shortage of facts about where, why, and how often charter school teachers are forming unions.

In a new report, we help shed light on unionization in charter schools.

Here are six things we’ve learned:

- Charter school teachers want more say. Many teachers we spoke with felt administrators and governing boards had lost touch with classroom realities and viewed collective bargaining as a means to ensure voice in school decision-making. The bargaining process, however, didn’t always provide clear mechanisms for teachers to weigh in on the things that mattered to them or repair the breakdowns in trust that often precipitated unionization drives. And, teachers could sour on unionization when union representatives insisted on contract demands—like tenure—that did not align with the unique culture or mission of their schools.

- Overall, the rate of charter school unionization isn’t increasing. During the 2009-10 school year, teachers at 12.3 percent of charter schools were unionized. During 2016-17 school year, 782 of 6,939 charter schools across the country were unionized—meaning the share of unionized charter schools had shrunk to 11.3 percent.

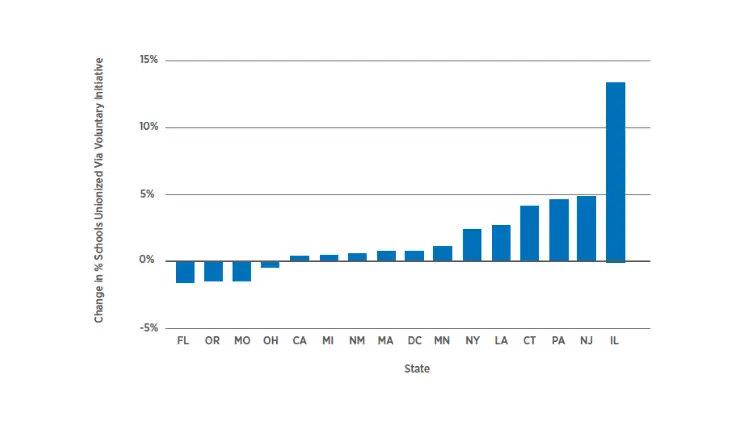

- Charter school unionization is on the rise in some places, especially Illinois. The Chicago Teachers Union launched a deliberate organizing campaign. It now represents teachers at a quarter of the city’s charter schools. Statewide, Illinois has one of the country’s highest rates of voluntary charter school unionization—and that rate has increased rapidly over the past decade.

Voluntary Unionization Efforts Gain Traction in Some States

From the 2009-10 school year to the 2016-17 school year, the percentage of charter schools that voluntarily unionized declined in Florida, Missouri, Ohio, and Oregon, but it rose in other states and climbed sharply in Illinois. Source: National Alliance for Public Charter Schools.

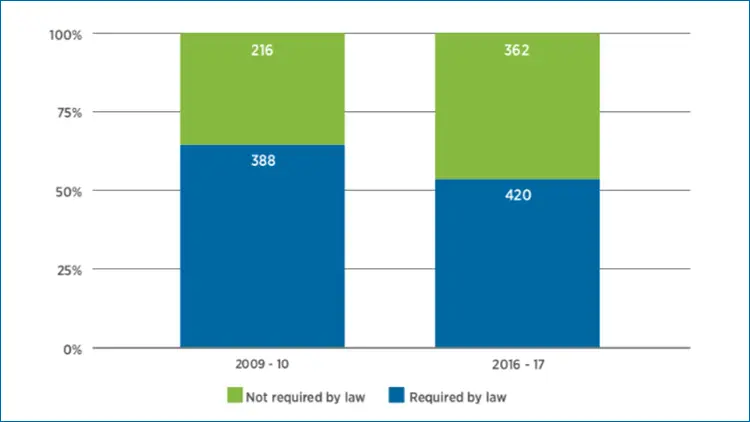

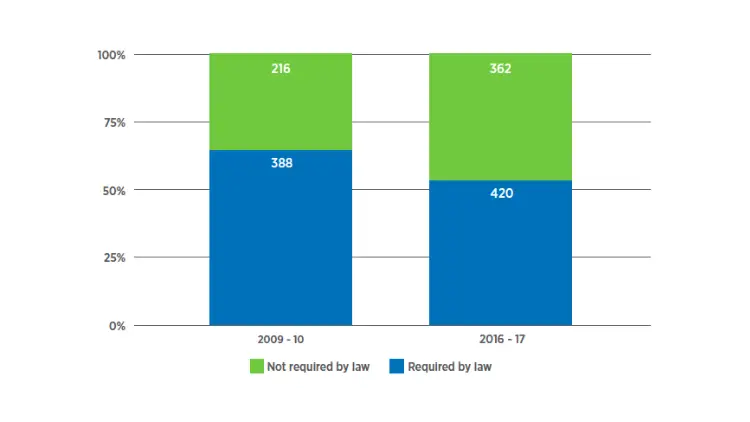

- The majority of charter school unions still organize as a result of state policy, but that majority is shrinking. In the 2016-17 school year, 46 percent of unionized charter schools organized voluntarily—meaning there was no requirement in state law for charter administrators to enter into a collective bargaining agreement (CBA) with their employees. That’s an increase of 10 percentage points from the 2009-10 school year.

More Charter Schools Are Unionizing Voluntarily

Comparing the 2009-10 school year and the 2016-17 school year, a growing share of charter schools formed unions even though state laws did not require them to do so. Source: National Alliance for Public Charter Schools.

- Collective bargaining agreements in charter schools look a lot like district contracts—with a few key differences. While charter school CBAs frequently embrace provisions common to district contracts, charter schools were more likely to give school leaders flexibility to decide how to hire, evaluate, and fire their teachers. One teacher told us: “We purposely left out tenure… The thing people don’t like about the union is that they protect crummy teachers.”

- Collective bargaining neither satisfies all of teachers’ concerns, nor validates administrators’ worst fears. As one administrator put it: “I took a stance that either I could feel really bad about our organization unionizing, or I could really get better as a leader and listen to our teachers more deeply. I took the latter stance and just really built my muscle in listening more deeply and responding with action.”

Together, these findings reveal missed opportunities for unions and charters alike. Unions stumble when they try to bring boilerplate provisions from school district labor agreements into charter schools. Charter school leaders too often dismiss teachers’ concerns, rather than empower educators to improve their schools.

Together, teachers and charter school leaders can forge a new model of labor relations that gives teachers a stronger voice in how their schools are run, and directs their voices toward improving results for students. That might look quite different from the model of labor relations that currently exists in school districts.