Weeks away from the end of the school year, it’s still unclear whether assessment data will play a role in shaping academic and social-emotional intervention strategies for 2021–22.

The Biden administration has told districts to resume statewide assessments so they can better target student supports for next school year—with a popular waiver system available for states that want flexibility in when and how the assessments will be done. But the administration has provided little guidance on how to assess remote learners, and a CRPE analysis suggests many districts lack a clear plan.

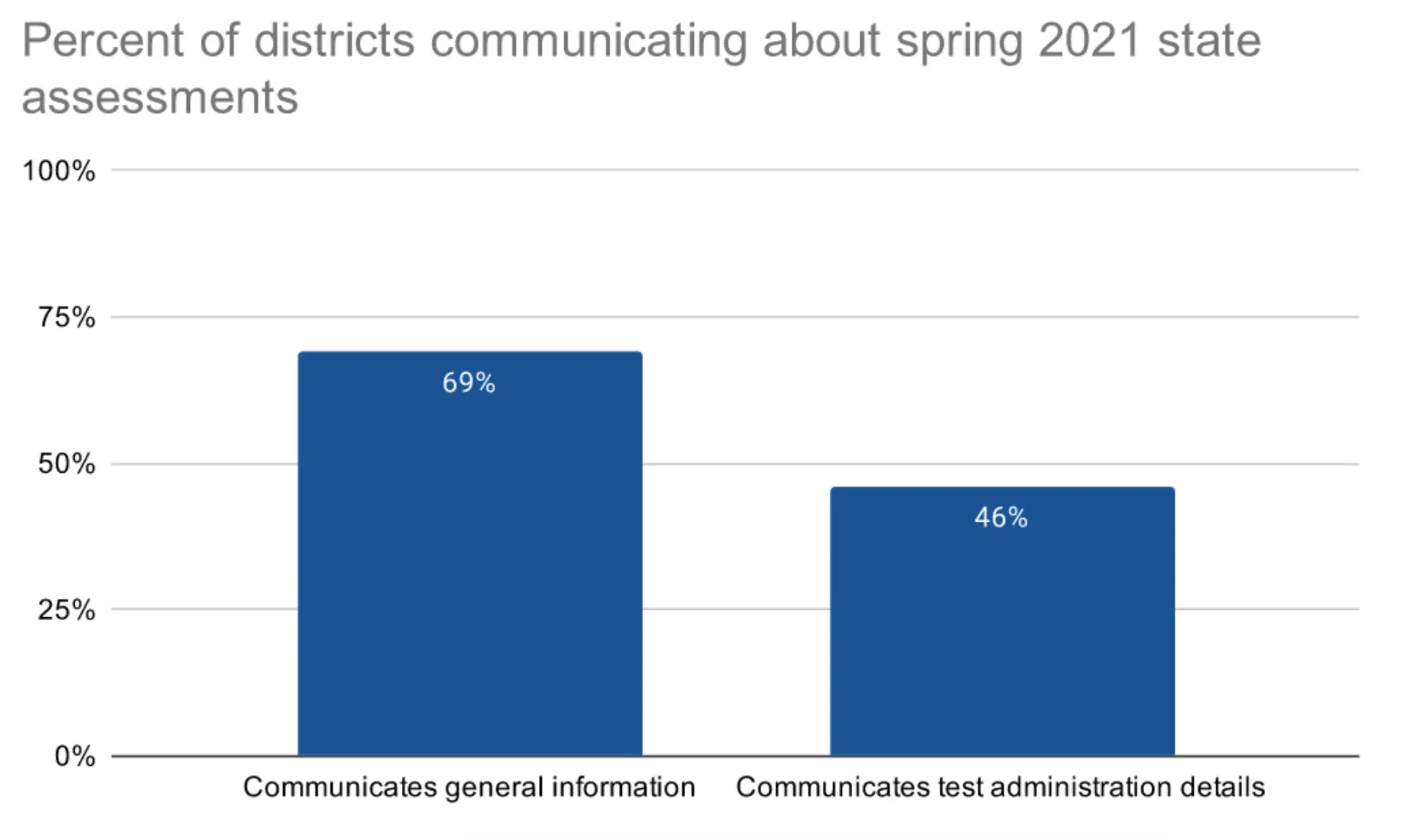

CRPE reviewed publicly available information on 100 large and urban districts’ assessment efforts. Only 69 districts share information about assessments, and only 52 of those districts share information regarding assessing remote learners. A significant minority of districts that do have a plan will not require remote students to take assessments at all.

The federal government may have offered accountability pathways with diminished stakes this year, but all should remain vigilant about understanding remote learners’ needs and supporting their academic progress. Given the imperative to get a handle on student achievement and needs, states and districts should publish information as soon as possible. Districts should also develop strategies to assess remote learners—those who are most likely to be falling behind.

District communication about assessments is vague and leaves out remote learners

Many districts appear to be in a holding pattern, not yet communicating how they will administer mandated assessments or more generally measure students’ progress this year.

The majority of school districts we reviewed (69) mention state assessments on their websites. But less than half of the 100 (46) provide any detail on how tests will be administered.

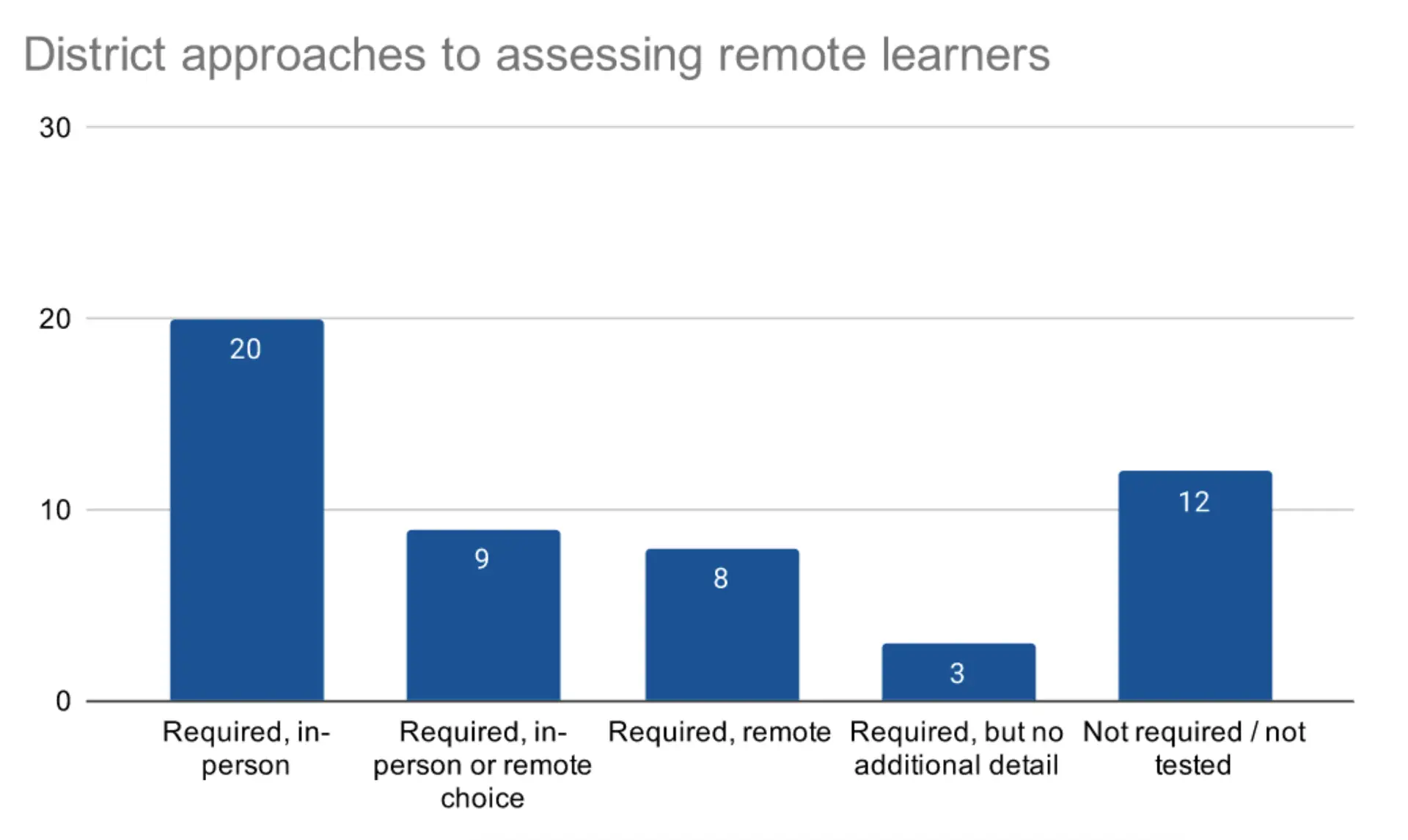

Only 52 districts delineate their plans for remote learners, with the greatest number of those (20 districts) requiring remote students to test in-person. Twelve other districts, including New York City Public Schools and Aurora Public Schools, will not require remote learners to take assessments at all.

Note: Based on 52 districts; remaining 48 districts provided no information.

The large number of districts that fail to mention assessment plans for remote learners (48) raises concerns about whether the country is on track to measure the progress of students who have had the least access to in-person instruction and support all year.

Nationally, a significant percent of students—more than half in many large districts, such as LAUSD—continue to learn remotely. Moreover, a disproportionate number of these remote learners are students of color.

Certainly districts can still measure student progress through internal assessments, and many conducted them remotely during the school year. Some have clearly stated this as their preference. However, if districts are planning to use this approach they are not advertising it.

Waivers result in a wide variety of student experiences

Digging into the assessment plans, we can already see how federal waiver decisions have resulted in a huge range in plans and approaches, even within individual states. It is not surprising that the bureaucratic endeavor of tracing assessment guidance between multiple levels of government resulted in a lack of clarity, but communication from the central office is still necessary. Assessments for remote learners can vary from district to district, so teachers and families need information to understand their roles and make plans.

- California: The state board of education voted to give all districts the opportunity to use either state tests (SBAC) or other standards-aligned assessments to gauge student learning this spring. The federal government agreed that this was permissible in lieu of a waiver. San Francisco and Oakland are administering district-level assessments (iReady, Reading Inventory) rather than state assessments, and requiring remote learners to participate remotely. LAUSD is also taking advantage of the flexibility by trading SBAC for diagnostics (DIBELS, Edulastic, and STAR) for all but grade 11 students. Their plan for remote learners is unclear. In contrast, Stockton USD offers the SBAC in-person and remotely.

- Colorado: The state received a waiver to eliminate science and social studies assessments and to assess students either in math or English Language Arts, depending on their grade. All assessments will be administered in person only. Aurora Public Schools, in line with state guidance, has excused students in remote learning from all in-person activities, including state assessments. Remote students can opt in to the in-person assessment if they wish, but the district will not provide transportation for remote students to take the test.

- District of Columbia: D.C. received a waiver to cancel all end-of-year state testing—the only such approval thus far. The Department of Education based its decision on the fact that 88 percent of students in D.C. were still in remote learning at the end of March, with hybrid students only receiving in-person instruction one day per week. There is no publicly available information about whether and how DC Public Schools will assess student learning this spring at the local level.

- New York: State officials also applied for a waiver to cancel end-of-year state testing, but the request was denied. Instead, the state used federally granted flexibility to significantly shorten this year’s assessments and will provide them only in-person. As a result, students who are learning fully remotely in New York City Public Schools and Buffalo Public Schools will not take the tests.

- Pennsylvania: The state did not seek a waiver from assessment requirements, but officials are delaying their state testing window until the fall, noting that 320 local education agencies were still operating fully remotely as of late February. The School District of Philadelphia, currently in hybrid learning mode, will conduct assessments only for in-person learners this spring, pushing their grades 8–11 Keystone Exams to fall for all learners. Districtwide progress monitoring that can be done remotely is proceeding for all students.

System leaders must take a plan for assessing remote learners

It’s clear that even a federal mandate to collect national data will not help us understand the complete picture of what happened with remote student learning this year. The variability in how assessment decisions and planning are playing out at the local level will be felt most acutely by remote learners, who are often our most vulnerable students.

At a minimum, districts must clearly communicate how they expect schools to measure and support remote learners’ academic progress. Otherwise, districts will be far less informed on how best to spend their stimulus funding to support student progress—and far too many families will be left in a holding pattern.

The challenge of assessing remote learners is not going away. About one-third of families nationwide continue to say they prefer remote or hybrid learning, and 32 percent of the large and urban districts we reviewed plan to offer a remote option next fall. Firmer expectations from federal and state policymakers, paired with clarity in communication from districts, would build more trust that the system cares about remote learners and increase the likelihood that interventions and support reaches these students.

Now is the time for the federal administration, states, and districts to set firm plans for assessing remote learners next year. Educators and families will need reliable feedback on how remote learners fare during the school year in order to inform instruction and at-home supports. Remote learners must receive the same personalized academic data, targeted interventions, and opportunities to demonstrate growth that all students do.