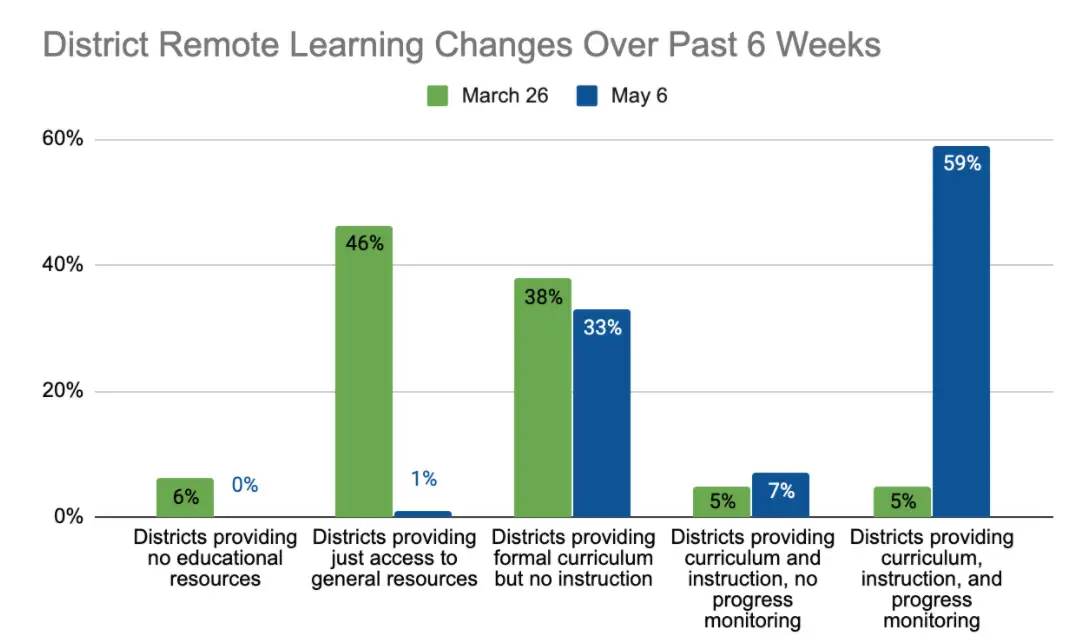

Since the middle of March, when schools across the country closed to stem the spread of the novel coronavirus, the Center on Reinventing Public Education’s nationwide tracking effort has told a story of school systems slowly making the transition from the classroom to the cloud.

Now, nearly two months into our nationwide tracking effort, most of the 82 school districts we reviewed provide some form of instruction. But 27 of them (33 percent), serving hundreds of thousands of students in some of America’s largest cities, still do not set consistent expectations for teachers to provide meaningful remote instruction. And 13 of those 27 additionally do not require teachers to give feedback on student work.

Note: Based on a review of 82 school districts.

They leave parents and students to make do with some combination of online assignments, paper packets and lessons broadcast over public-access television, with limited engagement from teachers.

We previously highlighted districts from Boulder Valley, Colorado, to Miami-Dade County, Florida, that took fast action under extraordinary circumstances to keep learning going during this pandemic. Leaders in these places often communicated, quickly and decisively, that teaching and learning would continue while school buildings remained closed.

The districts spotlighted here are often of similar size and demographic makeup to the fast movers, but they have been much slower to adopt remote instruction. We speculate that unclear expectations and mixed signals are big reasons why.

Difficulty reaching students

Nevada’s Clark County Schools is the largest district in our review that does not expect teachers to provide instruction.

The nation’s sixth-largest district distributed tens of thousands of learning packets and thousands of devices, but this has not been enough to reach all students.

The district reported that teachers had been unable to get in touch with more than 80,000 students the week of April 20 — roughly 1 out of 4 the district serves. That same week, according to the Las Vegas Review-Journal, more than 9,000 students were exempted from remote learning because they could not get online or find transportation to sites where the district distributed packets of assignments.

By contrast, in the country’s fifth-largest school district, Miami-Dade County Public Schools, 9 in 10 students are connecting to remote lessons and teachers are delivering remote instruction. Both districts must contend with poverty, language barriers and economically vulnerable workforces. And both districts have well-regarded leaders with reputations as change agents.

Those similarities make the disparities between the two districts’ remote learning efforts all the more noteworthy. The digital divide may play a role. The Las Vegas district sought donations to purchase tens of thousands of Chromebooks in the weeks after school closed, while Miami-Dade surveyed families on their technology needs and had devices on hand to distribute to them.

Delving more deeply into the reasons for these differences will help state and district leaders understand what it will take to support student learning through the summer and fall.

No expectation of learning, and no support

Milwaukee Public Schools has made learning resources available by grade level through Clever, an online platform. It has surveyed families on technology needs and delivered computers to students who didn’t have them. It offers packets of assignments that parents can pick up from schools serving grab-and-go meals.

But the district has also adopted a grading policy that implies that remote learning remains optional during school closure. Students will earn a “pass” or “fail” designation for courses they were taking this spring, based on assignments completed in the middle of the academic term — before the pandemic disrupted schooling across the country.

The district expects schools to contact students who have failing grades to help them find ways to pass. But its online learning plan does not communicate a clear expectation that teachers will provide instruction or feedback on student work.

The Milwaukee Journal-Sentinel reported that parents, educators and activists are up in arms, contrasting the lack of teaching in their city with efforts elsewhere in the country. Angela Harris, a member of the local Black Educators Caucus, said the district’s efforts have been “chaotic and unclear since the first day.”

“The biggest concern was the lack of planning and direction moving forward. Teachers could have been encouraged in those first three weeks to start identifying families who might be in need [of technology],” Harris told the newspaper. “We could have connected all the dots.”

Providing the clarity educators need to mobilize an effective response will be essential as school systems learn lessons from this spring and prepare for an uncertain fall.

Districts that leave decisions to schools and teachers—with uneven results

Students in Newark’s district elementary and middle schools receive work packets with half-hour daily assignments in reading and math and other subjects spread throughout the week. High schools are setting their own remote learning plans.

Chalkbeat has reported that remote learning varies from school to school, teacher to teacher and student to student, and that this patchwork has created confusion for parents.

The district has not reported attendance numbers that would allow tracking of which students it’s reaching and who is still falling through the cracks.

Decentralization can empower school leaders to respond to their communities and improve results quickly. But this crisis has shown that districts that set strong, systemwide expectations have been better equipped to keep more students learning consistently during the pandemic than those that did not.

Districts like Denver Public Schools have demonstrated that it’s possible to set high expectations in a decentralized system. Individual schools have the autonomy to tailor their remote learning efforts, but they must meet district expectations that teachers will provide instruction to their students and that they will track key metrics, like attendance, that monitor whether schools are reaching every student.

Preparing for an uncertain future

Some of the districts that have been slow to ensure student instruction have been quick to respond in other ways. The Milwaukee district, for example, acted swiftly to distribute food to families in need once schools shut down. Many districts have become broadband providers of last resort, or stopgap child care suppliers for front-line workers.

Districts must be similarly decisive when it comes to ensuring that teachers can continue teaching, and students continue learning, to the greatest extent possible — now, and through the inevitable disruptions schools will face in the summer and fall.

If schools and districts are hitting insurmountable barriers, states and the federal government must step in to help overcome them. But the differences among districts in our analysis suggest there are some factors school system leaders can, and should, control.

As the temporary disruptions of this spring give way to longer-term planning for the fall, all districts can draw important lessons from initial emergency responses across the country: Setting clear expectations across schools, and communicating them early and consistently, can help ensure that educators mobilize to keep students learning.