The COVID-19 crisis is exacerbating the challenges students experiencing homelessness face, as well as causing the number of youth who are homeless to grow. Education continues to be one of the most important components of their journey to break the cycle of poverty and reach economic independence, health, and well-being.

Yet these students’ needs have been neglected in both the national dialogue on the impact of pandemic-related school closures and school districts’ plans for remote learning.

For many students facing housing insecurity, schools are a primary source of meals, clothing, cleaning and laundry facilities, and counseling. School closures have intensified concerns surrounding food insecurity and safe spaces for students who are homeless, as well as the economically-driven digital divide.

In short, the pandemic has heightened the need for services, as well as the complexity in serving students experiencing homelessness. Yet our analysis of district reopening plans, combined with a national scan of surveys detailing these students’ needs and districts’ efforts to meet them, uncovers a surprising dearth of creative solutions—or even recognition of this challenge—by schools, districts, or states.

The 1.5 million U.S. students experiencing housing insecurity tend to be some of our most vulnerable learners and represent our most systematically and historically underserved populations.

Students who are homeless have an 18 percent chance of receiving services for a disability, which is 4 percent higher than the national average. Black and Hispanic students are additionally disproportionately impacted by homelessness, with Black youth and young adults having an 83 percent higher risk of reporting homelessness compared to their white peers. And students experiencing homelessness are over five times more likely to go hungry than their housed peers.

Districts that want to close long-standing equity gaps simply cannot do this work without placing these students at the center of their problem-solving.

Few districts even mention students experiencing homelessness.

Just 11 of the 106 school districts in CRPE’s reopening database outline plans to provide specific support to homeless and transitional students.

These 11 districts provide simple but compelling examples of prioritized support. Santa Ana Unified School District centers socioemotional, academic, and professional development initiatives around its students experiencing homelessness. It prioritizes free child care and extended day services for homeless students and provides free meals for all children. Academically, the district is coordinating tutoring services for students at hotels and shelters through school-based McKinney-Vento liaisons; the liaisons will train all teachers to identify and support students experiencing homelessness. The district has established a website for school liaisons to connect with parents experiencing homelessness and share resources, schedules, and community services, including mental health counseling. It has also established relationships with community-based organizations like the Orange County Department of Education Hopes Collaborative and the Orange County Family Solutions Collaborative.

Cleveland Metropolitan School District arranges visits with students experiencing homelessness to ensure that resources are adequately provided and will prioritize them for in-person instruction. Similarly, Oakland Unified School District has committed to serving its students facing housing insecurity in-person first, along with students with disabilities and foster youth, should the district return to in-person learning this year.

Indianapolis Public Schools is creating in-person “learning hubs,” where students experiencing homelessness can complete schoolwork, and is working with community partners to create a student support network for other students to do virtual work with supervision.

Because of the challenges maintaining communication and contact with students moving between homes or shelters, these prioritized services also depend upon intentional communication plans to find and stay in touch with students and families experiencing homelessness. We are not seeing specifics of what this will look like in any publicly posted plans.

Digital access to educational services during remote learning is an important first step.

Providing equitable access to vulnerable populations amid the COVID-19 crisis does not look the same as it did before the pandemic.

Just one in four districts expected schools to track student attendance last spring, and those that did found attendance in remote learning significantly lower than under normal school conditions. The Los Angeles Unified School District estimated that about 40 percent of secondary students were largely or fully absent from learning on any given day.

Now that districts are signaling a move back to remote learning for the start of school this fall, digital access will become the bridge that allows many students facing housing insecurity to participate in schooling and access services. But schools and districts will need help building that bridge for students who need it most.

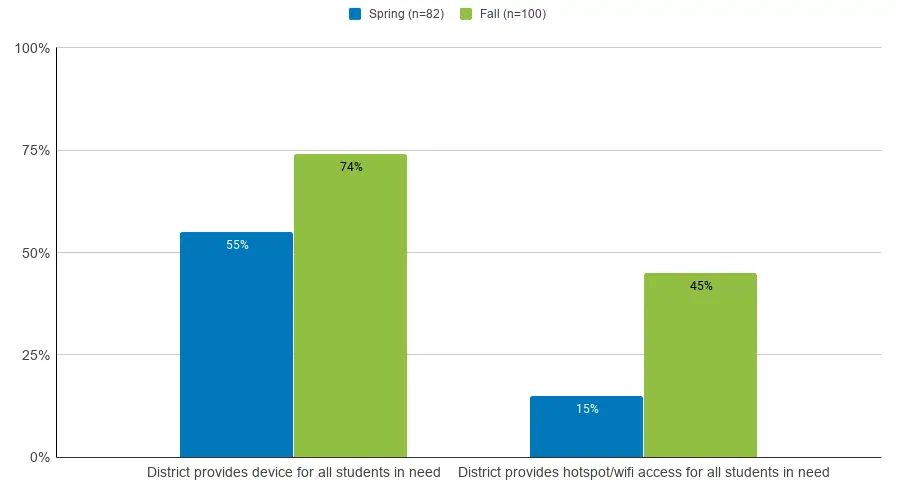

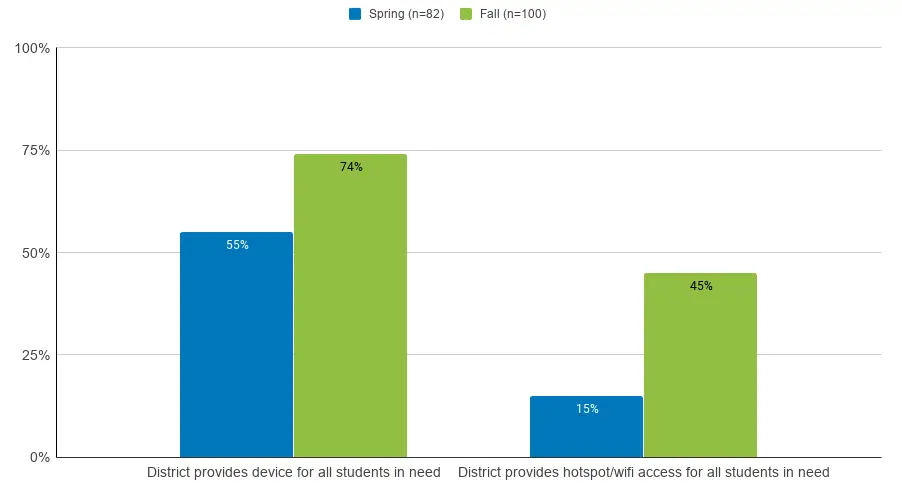

Of the 106 district plans reviewed, about three quarters have publicly committed to providing devices, but less than half have committed to providing universal wifi access for students in need. Comparing these rates to last spring’s, there is improvement but it doesn’t look like all districts have found a solution for bridging this gap.

District approaches to digital access

Beyond providing physical wifi access to remote learning, districts have an obligation to build holistic and individualized opportunities to support remote learning. This could include creating wireless internet hotspots that all students who are homeless can consistently access, providing satellite locations for food pickup, and providing social-emotional learning and mental health support. It also includes training educators to create instructional methods that are flexible enough to accommodate the challenges that homeless students face.

Partnerships with nonprofit initiatives are part of the solution.

Education is a critical part of the long-term solution for supporting students experiencing homelessness. But these students can only access education if their families’ basic needs—housing, meal provision, and healthcare—are also met. Nonprofits and local social service agencies are vital partners in providing such resources for students who are homeless—which school districts could better leverage to prioritize their own limited resources.

Because students and families experiencing homelessness receive social services and support from a range of government and philanthropic funds, there is an opportunity—and unprecedented need—for states and districts to enter this fall with a comprehensive wraparound services plan that places education and schooling access at its center. An effective way to achieve this is by partnering with local organizations who provide complementary services. This can be challenging to execute, but it has never been more essential.

Many of the districts we see paying attention to their population of students and families experiencing homelessness are doing so based on partnerships with community-based organizations. In fact, schools that most effectively serve these students emphasize the importance of robust community-school partnerships, including housing agencies, social services agencies, the business community, and faith-based organizations. They also build multifaceted systems that strive to meet student needs rather than accommodating needs within predetermined systems.

Within weeks of last spring’s school closures, the Seattle Foundation set up a now-$10 million fund to support local community organizations. $725,000 has been granted to organizations that provide services to homeless individuals, including a $50,000 grant for YouthCare, a nonprofit that supports homeless youth.

Similarly, the Raikes Foundation and Building Changes have collaborated to create the Washington State Student and Youth Homelessness COVID-19 Response Fund, which supplements the public funding available to homeless youth in order to combat the exacerbated effects that these youth face because of the pandemic.

Districts, already strapped for resources, have an opportunity to leverage local nonprofits that are funded by local philanthropy to serve families experiencing homelessness and to communicate this commitment clearly.

Most states are missing the opportunity to facilitate solutions.

The districts noted above are among just a handful that are prioritizing support for students experiencing homelessness.

States have been almost entirely silent on expectations or support to districts in their reopening guidance. Only a quarter of states we reviewed (13 of 49) reference their population of students experiencing homelessness. This is surprising and disappointing, given state educational agencies’ close proximity to other agencies that complement the work needed to support students who are homeless, such as state healthcare or housing agencies.

States actors can and should play a role during the crisis to set expectations, channel resources, and facilitate partnerships across education, healthcare, and housing agencies to combat simultaneously the pandemic crisis, the looming economic recession, and school closures. While state-level task forces are meeting to resolve health and economic crises, a similar approach could be stood up to resolve the crisis of remote learning for their most vulnerable populations. States are well positioned to serve as information brokers—linking resources between social service agencies and local educational agencies to facilitate smoother coordination of services.

A state might, for example, provide financial incentives for locales to form partnerships working toward joint school/healthcare/housing solutions during school closures. The Governor’s Emergency Education Relief fund (GEER), established in the CARES Act, allows governors to apply and distribute grants to local education agencies for carrying out emergency educational services, providing child care and early childhood education, providing social and emotional support, and protecting education-related jobs.

States could also require districts to put in place a comprehensive plan to serve this population of students, and monitor districts’ use of federal funds specifically allocated to help districts serve students experiencing homelessness. States could also help districts think about how they can tap existing program dollars, like Title I, to put in place comprehensive wraparound services.

Some states are tapping new federal funds to promote digital equity collaboratives. Under the Department of Education’s Rethink K-12 Education Models Grant, 12 state educational agencies received federal funding to promote innovative remote learning models, including digital access, in collaboration with local nonprofits.

Louisiana will receive $17 million to pilot a family microgrant program to support their procurement of devices and broadband. South Carolina received a $15 million grant and is developing datacasting, which will allow for students to receive instruction through an encrypted signal—bypassing the need for internet access. Both of these programs focus on resolving the digital access issues, via partnerships, that must be addressed for students who are homeless to participate in remote learning.

While districts churn with myriad unanswered questions surrounding the upcoming school year, we hope and expect to see state leaders coordinating resources and strategies that school districts can offer their students and families experiencing homelessness. Instead, what we see is largely nothing.

While an economic recession looms, a coordinated approach to leveraging community partnerships and federal funding is likely the only way states and districts will deliver on their commitment to not exacerbate long-standing inequities already baked into their systems.