During the 2020–21 school year, a large share of students opted to enroll in established, full-time virtual schools.

Our analysis of federal enrollment data suggests parents, perhaps dissatisfied with remote schooling or concerned about the safety of in-person learning, sought new alternatives to traditional school districts during the COVID-19 pandemic.

We examined data from the National Center for Education Statistics for eight states that had publicly posted enrollment data for the 2019–20 and 2020–21 school years and had at least 200 students enrolled in districts that operated “exclusively or primarily” virtual schools. We found:

- Virtual school enrollment spiked the most in states that already had relatively large virtual school enrollment, suggesting parents were seeking options that offered more robust virtual learning.

- The largest expansion in virtual school enrollment occurred in elementary grades, where online learning was previously far less common.

- The flight to virtual schools could only account for up to 40 percent of traditional districts’ enrollment declines in the states we examined, suggesting it was a major factor driving enrollment loss, but not the only one.

Our analysis did not include online options within schools or virtual schools that were part of traditional districts, which means it likely understates the magnitude of the enrollment shift into full-time virtual schools during the pandemic.

The pandemic accelerated a trend that had already been underway for years: more students enrolling in virtual schools. This brings new challenges for policymakers and school system leaders. Virtual schools have a spotty record of success, and large enrollment shifts pose a potential financial threat to traditional districts.

At the same time, the pandemic has underscored how the safety and flexibility of online learning make it a useful option for families, especially in times of crisis. Families in many districts are demanding more online options as they return to school this fall. Policymakers should look for ways to help school districts design virtual programs that meet these families’ needs, and focus on improving the effectiveness of online learning.

Virtual school enrollment increased during the pandemic but primarily in states with established programs

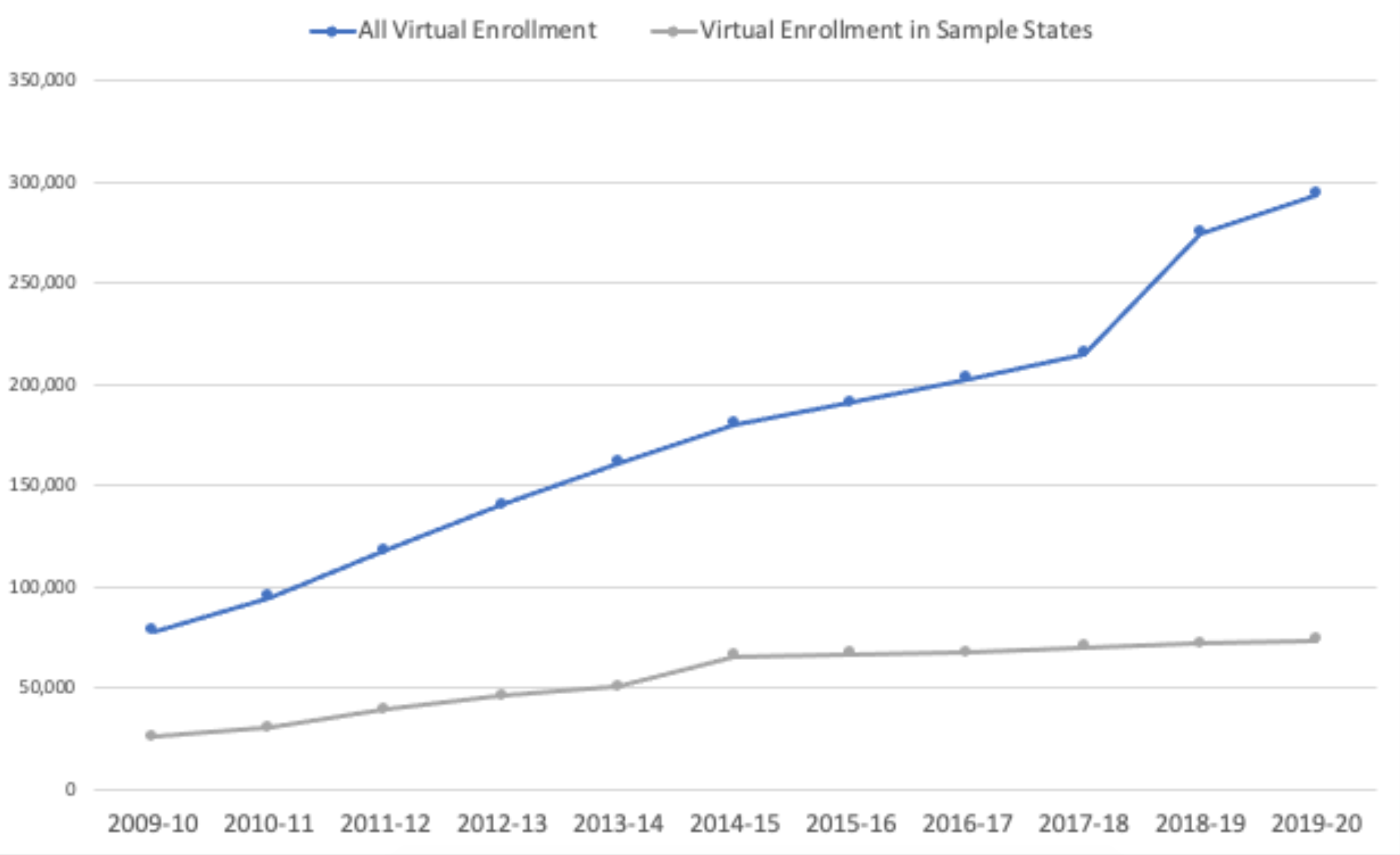

Virtual school enrollment had been rising for years leading up to the pandemic (figure 1).

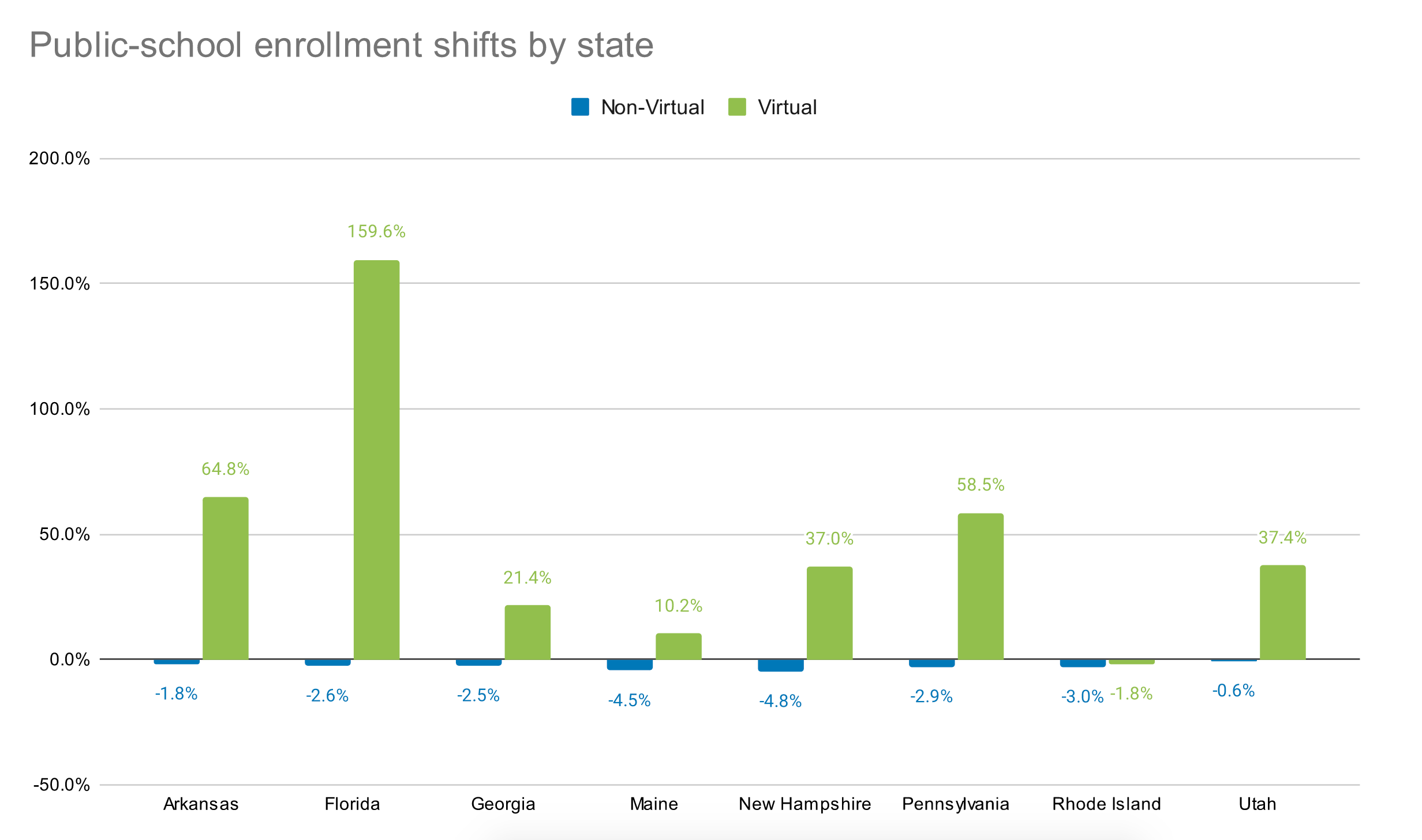

Enrollment data for 2020–21 in the eight states we examined shows a clear increase in virtual school enrollment and a decrease in in-person district enrollment. However, enrollment trends vary substantially across states. States with higher virtual enrollment and, presumably, more established virtual providers pre-pandemic—Arkansas, Florida, Georgia, Pennsylvania, and Utah—saw the greatest percentage growth during the pandemic year (figure 2).

Notably, enrollment in Florida Virtual School more than doubled during the pandemic. Meanwhile, enrollment in brick-and-mortar districts declined between 0.6 percent and nearly 5 percent.

Figure 1. Virtual school enrollment had been rising long before the pandemic

Note: Virtual schools were given a different classification scheme before the 2016–17 school year. For consistency, we provide a backward-looking aggregate enrollment trend for all schools classified in the Common Core of Data as “full virtual” in 2019–20. ElSi Table 170557. Sample states include AR, FL, GA, ME, NH, PA, RI, and UT.

Figure 2. Enrollment increased in virtual schools and decreased in districts during 2020–21

Note: Enrollment changes reported only in states with data available on district-level enrollment. Virtual school enrollment includes schools that are identified as local education agencies and where the majority of students were enrolled in schools classified as “primarily virtual” or “exclusively virtual” before the pandemic.

Early grades see the largest jump in enrollment

Historically, younger students have been less likely to enroll in fully virtual schools. According to 2019–20 NCES enrollment data, students in grades K–5 made up only 22 percent of total virtual enrollment.

Of the eight states we examined, six (Arkansas, Georgia, Maine, New Hampshire, Pennsylvania, and Utah) report enrollment by grade. In these states, virtual school enrollment in grades K–5 jumped by 112 percent, while virtual school enrollment in grades 6 and above increased by only 23 percent.

Enrollment changes prompt new questions for policymakers

Virtual enrollment may see a lasting bump from the pandemic. It isn’t yet clear how many students who opted for virtual learning last school year will return to virtual learning this fall. We do know from surveys that a small but substantial number of parents are reluctant to return their children to in-person learning, and pressure is mounting on states and school boards to expand virtual learning options. Many states—like Tennessee—are seeing a proliferation of new or expanded online schools.

Virtual schools, however, have a spotty track record, with studies showing that they tend to have higher student-teacher ratios than in-person schools, and student performance on standardized assessments tends to be mixed, with online charter schools and for-profit vendors consistently showing poor outcomes and other virtual programs showing more positive outcomes. That said, some students may have found success in these programs, which are clearly cementing their place in the education landscape. States must monitor enrollment trends in the virtual sector and ask:

- Which students continue to enroll in virtual schools and why are they opting out of traditional in-person learning? What learning experiences are they seeking in the virtual classroom?

- What is the composition of the student body in virtual schools? Are students from low-income households, students of color, and students with disabilities enrolling in these schools at the rate they enroll in traditional schools?

- Do students who are eligible for additional support (e.g., breakfast and lunch benefits, counseling, special education services) receive these services?

- Do students enrolled in these schools show the expected academic progress and social-emotional development? What factors in the approach to virtual learning, support for students, or conditions for learning are associated with that success?

- How are school districts responding to parent demand for virtual education? Are they increasing their own capacity to serve students virtually, either through partnerships or schools they run themselves, or are they losing students to statewide options or virtual charter schools?

One lesson from the last eighteen months of pandemic learning is that our education system must offer a diverse set of learning environments.

For some students, virtual learning has been and will continue to be a sought-after option. That option is more visible and accessible today than in the past, and virtual schools are likely to be seen as an important safety net during health-related disruptions and school closures linked to weather events and other natural disasters.

But in general, families and schools need high-quality virtual options. Now is the time to approach virtual learning with rigorous inquiry and the goal of improvement.

Kristin Blagg is a senior research associate in the Center on Education Data and Policy at the Urban Institute. Betheny Gross is the research director at WGU Labs.