This is the second in a series of updates on our findings on school district response plans. See our latest analysis here.

Last week, we released an initial database of district responses to COVID-19, which tracked how districts were serving the basic needs of their students and families in the face of school closures.

Since then, states have sharpened their guidance to districts as they confronted the prospect of long-term remote learning. At least seven have announced they would be closed for the remainder of the school year. Others, like Minnesota, extended the period of time physical schools would be closed, sharpened expectations for schools and teachers to ensure learning continued, and clarified that schools would be in session, albeit remotely, in the coming weeks.

This week has been a crucial period of preparation in states from Washington to Florida, where distance learning is expected to begin in earnest by the end of March. Some districts used this week to iron kinks out of their plans and ensure students will have access to technology.

This week, we have updated the database to represent 82 districts serving approximately 9 million students. This update incorporates new data on teaching and learning. The bottom line is that districts are trying, but have a long way to go.

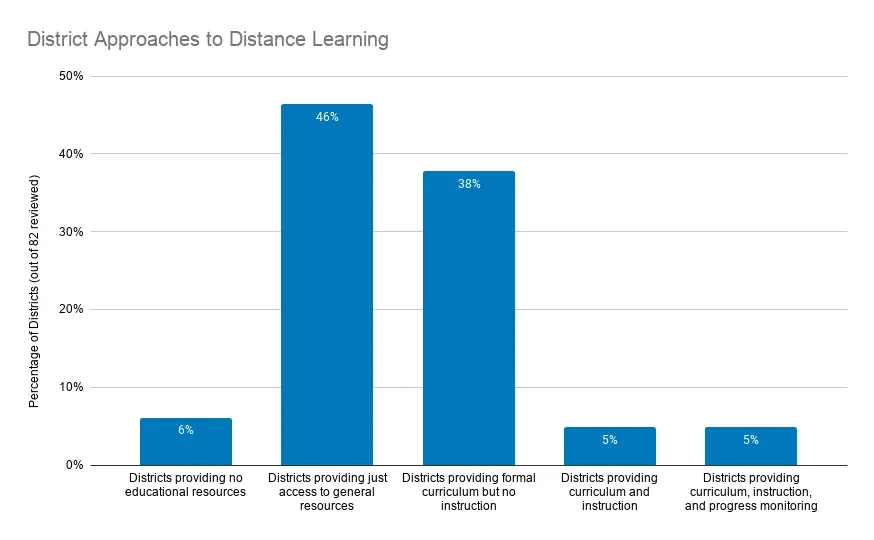

- Most districts are still not providing any instruction. The majority provide links to general online resources but no direction on how to use them. Some districts (38% of those reviewed) go further to provide formal curriculum, but not instruction. Five districts (6%) have released no information about distance learning plans or access to general resources. More districts have rolled out new plans, however, so we can soon expect to see a larger share providing some kind of instruction.

- Of those providing instruction, few provide something akin to a comprehensive educational experience. This week we looked more deeply to assess how many districts seem to be providing what could be considered a coherent instructional experience. Just four districts (less than 5% of those reviewed) provide formal curriculum, online instruction, and student progress monitoring.

- None of the 82 districts we reviewed say they are attempting fully “synchronous” learning, where students engage in live discussions with teachers and classmates—though efforts in Cobb County, Ga., where educators are building community via Microsoft Teams, come close. The other districts appear to be engaging in “asynchronous” or “hybrid” remote learning, where students view daily instructional videos from their teachers, or receive daily assignments and feedback.

- Connectivity remains a nagging question. About 40% of districts reviewed are providing devices, up from a third last week. About 15% provide mobile WiFi/hotspot access, a slight improvement from last week. However, as the New York Times underscored citing CRPE data in a recent editorial, students across the country remain shut out of digital classrooms, and this remains a major unmet need in many school districts.

Note: Districts’ approaches continue to evolve over time and have the potential to shift categories as they add to their distance learning plans.

In addition, these other trends emerged:

Meeting the needs of students with disabilities and other special populations remains a big missing piece for many school systems. More districts are providing online resources for parents of students with special needs (43% of districts reviewed this week, compared to 24% last week), but information on how special education services are being delivered is not clear for most. Districts may refer parents to follow up calls from teachers or case managers. The New York City Department of Education, Houston Independent School District, and Anchorage Public Schools plan to provide special education direct instruction and IEP-related services for individual students by video or phone.

Learning plans skimp on student diagnostics, remediation planning, and general progress monitoring. A critical component of effective distance learning is monitoring and tracking student progress, either informally through teacher check-ins and feedback or formally through assignments and grading. Without this data, a distance learning plan becomes a blunt tool for identifying and filling student learning gaps.

To date we have observed 12 districts (15% of those reviewed) that expect teachers to reach out or be available for check-ins with students, and 6 districts (7%) that expect teachers to grade student work. Suspending teacher check-ins makes sense in the short term, as many districts are still on spring break or extended closure, and resuming them is likely a second-order decision after a district has established its distance learning plan. However, if distance learning becomes a longer-term reality, creating plans that monitor student attendance and performance will be critical. Districts using online platforms like Google Docs or digital learning software like i-Ready will be able to monitor student learning more effectively while remote than those relying on paper work packets.

Significant burdens fall on parents. The reality of distance learning is that the home becomes the “school,” and some instructional responsibilities transfer from educators to parents and students. What is being asked of parents at this time is tremendous. Most distance learning plans we reviewed still essentially require parents to plan and execute lessons, and monitor their child’s work.

Many well-intended distance learning assignments we reviewed would not pass muster in a traditional classroom. They may not align to grade-level standards, or take into account student diagnostic data, or provide necessary materials. Districts require that teachers go through years of training and certification, and COVID-19 has thrust parents overnight into a role that expects the same level of sophistication to work effectively. Keeping teachers connected to their students at this time, ideally through online instruction and not just work assignments, is an essential next step as districts get more serious about distance learning.

We continue to track how districts provide training, resources, and support to parents. Jefferson County Public Schools in Kentucky provide resources in five languages, as well as video, and are building out a “Parent Toolkit” that will include instructional support training for parents and a hotline for families seeking support.

Connectivity remains a nagging question. Even once a district has created a digital learning plan, and communicates it well to families, it still must ensure students have access to technology. This is a pervasive operational and financial challenge for school districts we reviewed.

Without a full technology solution, universal student learning simply won’t happen. We are continuing to mine the field for creative approaches that are getting real results. Here are a few we’ve found so far.

- The New York City Department of Education, in partnership with Apple and T-Mobile, is distributing internet-enabled iPads to every family expressing a need in the district.

- Atlanta Public Schools, in partnership with T-Mobile, distributed 9,000 mobile hotspots to individual families.

- Guilford County, N.C., has set up eight hotspot hubs in school parking lots.

- Charleston County School District, in South Carolina, places hotspot bus hubs in community centers.

- Kansas City is partnering with the nonprofit LEANLAB Education to distribute devices and hotspots.

Some districts are delegating distance learning plan decisions to schools. About 13% of districts reviewed are decentralizing decision-making on distance learning to their schools. Oakland Unified School District posts that each school is developing its own “continuity of learning” plan which should include lesson plans, resources, and directions for communicating with teachers. This approach will be interesting to watch. It may give schools and teachers more flexibility to customize learning plans, but it also creates the potential for greater variability in quality and raises the concern that the schools serving students with less stable housing or lower broadband connectivity will face greater difficulty executing meaningful distance learning plans.

Perhaps the best way forward is the simplest. We’re seeing a huge range of approaches, and no one knows what works best. We’re eager to learn how districts change and adapt as they experiment.

So far, few districts have set up at scale what may be the simplest solution: connect classrooms of kids to the teachers they’ve known since the fall, and have them carry on with their lessons where they left off. This does seem to be happening in one-off circumstances, but it is driven by individual teachers’ initiative than a specific district expectation.

Our emerging advice to districts would be: Don’t overcomplicate this. Give your teachers some planning time. Expect it to take a while to work out kinks. Just like we tell students, making mistakes is okay. Get creative when you need to. Get local businesses and city leaders to help. But most of all, start trying things—and give educators space to try things, knowing not everything will work.

All of the districts mentioned here are trying, and they are learning and improving. The most inequitable thing a school district can do right now is nothing. Affluent families who can hire private tutors or buy online programs for their kids are compensating for public school leaders’ inaction. Our most vulnerable students have the most to lose if school system leaders don’t make efforts to support every student.

Hopefully, there will be a quick end to this crisis and kids can be back in school soon. But epidemics may last a while or come in waves. And our schools need to be prepared for the next emergency, whether it’s a disease outbreak, an earthquake, a wildfire, a hurricane or a snowstorm. The systems schools develop now can help us ensure student learning is more resilient in the future.

CRPE will continue to expand our database and update it weekly. We are developing graphics to present the data we gather in a more engaging way. We welcome suggestions and partnerships. The challenge before our school systems is historic and will require collective action.