We are looking for more examples of learning pods and hubs. If you know of any, please let us know by filling out this short form.

In October, 100 Black Men of Valdosta, in Georgia, transformed their space into a free virtual learning site for students who lack stable internet or have other needs. They stepped in, the director said, because “someone had to.” The organization partners with local school systems to enroll students who receive transportation, breakfast and lunch, and academic support. Hundred House mentors have access to student grades, behavior reports, and attendance reports, giving them more visibility into students’ academic lives so they can more effectively “shape and mold the lives of young people.”

Across the country, parents, civic and community leaders, school districts, and businesses are stepping up in similar ways, launching efforts to close gaps in digital connectivity and childcare access—and, in the process, breaking down barriers between schools and communities.

The phrase “pandemic pod” evokes wealthy white parents hiring a teacher and gathering a small group of friends in a fancy greenhouse or a Brooklyn brownstone. These pods do exist in wealthy communities, and people rightly fear that such privilege can lead to widening inequality and segregation.

But families, communities, and public schools are also creating new arrangements that aim to solve the same problems as their ritzier counterparts: giving students safe places to connect to school and receive support from caring adults.

Today we are launching a national database that will catalogue and make sense of these initiatives, with an eye toward equity. Through a scan of the media reports and established resources (like National School Choice Week’s compilation of virtual learning supports), recommendations in our networks, and our work to track district reopening plans, we have uncovered over 160 of these school- and community-driven learning pods and hubs, with more added every week. This isn’t an exhaustive list, and we welcome our readers’ recommendations of additional efforts to track. Our tracker does not try to capture family-run pods.

Our initial analysis reveals that though they all seek to serve students and families during the pandemic, learning pods and hubs differ in who runs them, what they offer, how teaching and learning happens, who they serve, and the potential to redefine what normal school looks like.

Who’s the provider?

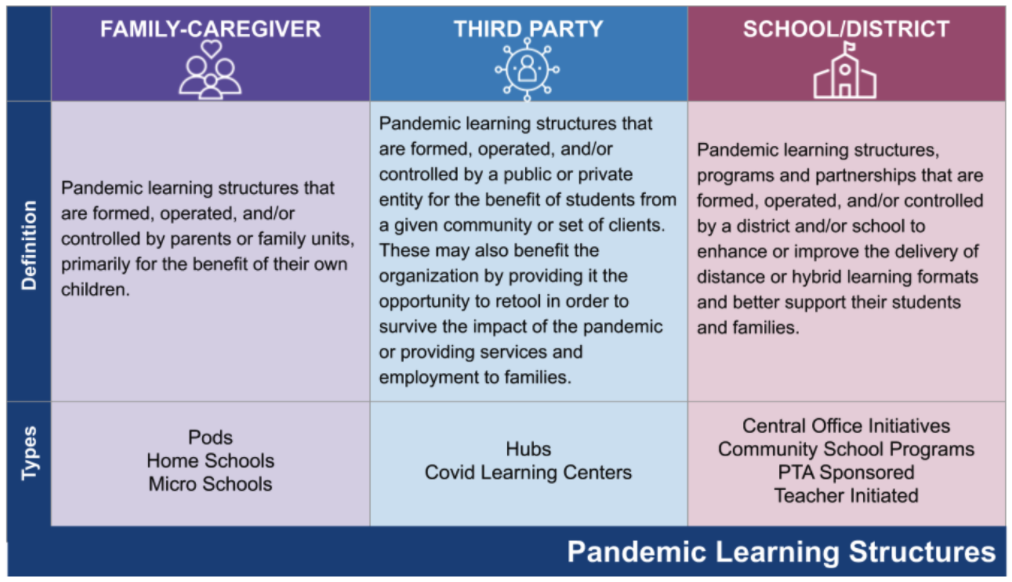

A wide range of private, nonprofit, and government organizations are offering pod-like support, either directly to students or by providing support to families to run more effective pods from home. Carolyn Gramstorff has a nice primer on the variation by type.

Source: Mapping the Pandemic Learning Landscape, by Carolyn Gramstorff

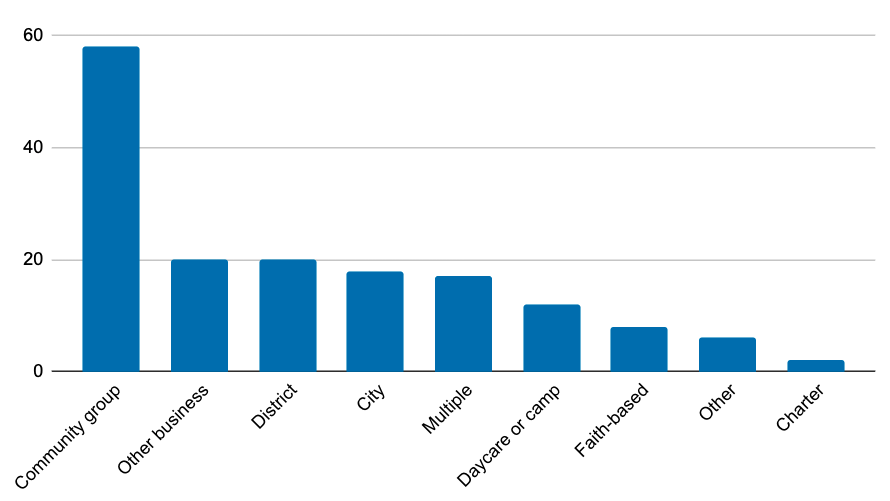

Our tracker shows that community-based organizations like the YMCA and the Boys & Girls Clubs of America are major contributors to the rapid expansion to pods across the country. At least 58 of the 160 hub efforts in our tracker are run by these organizations or partner with them. Faith-based organizations, afterschool providers, and other youth service organizations are supporting similar efforts in their communities. Faith-based organizations operate eight of the learning hubs in our database.

In Charleston, SC, the district partners with churches and other local organizations to support virtual learning. An elder at one of the churches said he considers the effort a fulfillment of a longtime vision of his church: “So this is really getting back to the roots of what used to be so common in the Black community. We really wanted to be a part of that bedrock foundation of helping children learn and families grow.”

Many types of organizations operate learning pods

School districts are sometimes operating these supports. In Arizona, Mesa Public Schools operates onsite support centers, which provide a safe, supervised space for students to access remote learning. The state requires school districts to provide this support to students in need, including children of first responders, foster children, students with disabilities, and students lacking technology or supervision at home.

Other districts are coordinating or promoting efforts run by community partners. Across the 100 mostly urban districts that are a part of our COVID-19 response project, 22 coordinate or promote learning pod efforts provided by others, typically community-based nonprofits. Sixty-six districts provided no information on learning pod opportunities, leaving families on their own to figure out support for learning and childcare. Given the prospect of continued school closures, it will be important to see whether more districts work to provide in-person learning support to families who need it.

What services are offered?

Learning pods fulfill some basic needs that arise when schools shift to remote learning, like adult supervision and wifi access. Families and children may also benefit from the opportunities for social interaction and structure to the school day. One mother we spoke with said her teenage son was getting depressed staying home every day and didn’t want to get out of bed. Going to a learning hub created by the Cascade Midway Charter School (recently renamed Why Not You Academy) helped motivate him.

Most learning pods offer at least minimal academic support, even if it’s just helping kids stay on task in virtual learning. Some go much further, offering intensive tutoring, mentoring, or social-emotional support. In partnership with World Finance and the Come Out Stronger program, North Hill Church of Taylors in Greenville, SC, offers a pod for up to 24 children that includes tutoring by qualified instructors and remote learning support.

At the extreme are pods that provide all instruction themselves, like a microschool or a homeschool co-op. Prenda Learning partners with charter schools in Arizona to provide micro-schools tuition-free. Parents are paired with a “guide” who supports students as they work through a blended learning model.

Pods often offer enrichment activities, like sports, science, and arts. The Frost Science Museum in Miami offers school-day learning pods and afterschool enrichment. Museum educators help students during their school day and support access to science-based enrichment programs. In Madison, CT, the Friends of Madison Youth-Arts Barn supports students who learn in the district’s hybrid learning model and leads students in theatre activities as enrichment.

What does teaching and instruction look like?

Most of the third-party or district-run hubs rely on virtual instruction delivered by the child’s teacher with in-person “facilitators” (typically childcare and afterschool providers, or district non-teaching personnel, like cafeteria workers or central office administrators). This aligns with survey findings, which suggests parents use pods to supplement, not supplant, instruction provided by traditional public schools.

The redeployment of so many community members offers an unusual opportunity to bridge some of the gaps between schools and community-based organizations. We’ve heard stories that district staff are delighted to have the chance to work with kids more directly and that community-based organizations are finally finding ways to realize their goal of tighter coordination between social service providers and schools.

The opportunity is exciting, but there are also risks. While unionized teachers are at home, lower-wage workers are taking on the health risk of working with students. In some cities, childcare workers are prohibited by state or local regulations from doing anything close to teaching, an agreement likely negotiated with teachers unions.

Many programs are free or low-cost, but in some cases this cost structure is subsidized through temporary investments like federal CARES dollars or philanthropy. How to sustain them throughout the pandemic, and possibly beyond, remains a question.

Many well-intentioned organizations have stepped up to offer learning support to students and families, but whether they are fully prepared to meet students’ and families’ needs during the crisis will be important to watch.

While some states, like Indiana, made emergency provisions to allow for learning hubs, the “just right” regulatory structure that allows more community members to teach without forgoing important protections for students will be critical to get right. But getting it right has the potential to offer new learning environments to students that blur the lines between school and community, or during school and out-of-school time—changes that have the potential to improve the learning for students after the pandemic passes.

Short-term crisis response vs. long-term vision for holistic education?

The first order of business for any pandemic learning pod is to ensure basic needs are met: a safe place for kids to be, stable wifi to do remote learning, and some opportunities for social interaction are all critical elements.

Some of the efforts we’re tracking began that way but are now expanding to something more as community organizations bring their talents and resources to the table: enrichment activities as wide-ranging as arts, mental health supports, mentoring, and tutoring are all coming into play at some of these sites.

Some of the more ambitious efforts go well beyond that, however, to redefine what the normal learning experience looks like.

The Oakland REACH, a parent advocacy group in Oakland, CA, created a virtual learning hub that provides direct learning opportunities to more than 200 high-needs students, along with family liaisons to support remote learning through the district. The liaisons help families navigate the complexities of virtual learning, but also advise them about the education their child is getting or should be getting. Lakisha Young, REACH’s director, said the goal is not continuity of learning, as many of her families were not being well served pre-pandemic. The goal is to “tackle gaps and shake up the system.”

Edgecombe County Public Schools in North Carolina is a rural district that uses learning hubs to pilot new ways to support middle and high school students, including more flexible schedules and opportunities to serve students with common needs and interests. The district has a history of using micro-schools to pilot new curricula, and is already thinking of hubs as a permanent part of the menu of learning options it offers students.

We must learn from these efforts in real time

There are several big takeaways here. First, it is amazing to see communities step up to this crisis to serve students—despite the costs, the health risks, and the effort required. Second, it’s striking to see the diversity of learning environments that arise when communities build them from scratch. And third, these new arrangements may open up new possibilities for social-emotional learning, enrichment, and community-building to be woven more tightly into the traditional school day.

Many of the ways in which parents and communities are building pods and hubs are so compelling that, already, parents and civic leaders say there is something too valuable here to let go of if students return to regular classrooms and schools. They’re starting to think differently about what regular classrooms and schools ought to look like. There is a fast-building case to learn from these efforts.

As the pandemic surges and more schools are forced to close, CRPE will be watching as these small pandemic learning communities continue to grow. We are launching a national research project and researcher consortium with support from the Walton Family Foundation, the Michael & Susan Dell Foundation, the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative, and the Joyce Foundation.

CRPE and our collaborators will track and document these efforts through our national database of learning hubs, our surveys and interviews with educators and parents participating in pods and hubs, and through a series of deep dives that aim to understand how these new learning communities are shaping students’ and families’ experiences with school. Our aim is to learn as much as possible from these efforts to inform a path to rebuilding that is more just, equitable, and responsive to individual student needs.