Students who are unhoused or in housing transition, an already vulnerable population before the pandemic, are falling even further out of sight in the 2020–21 school year.

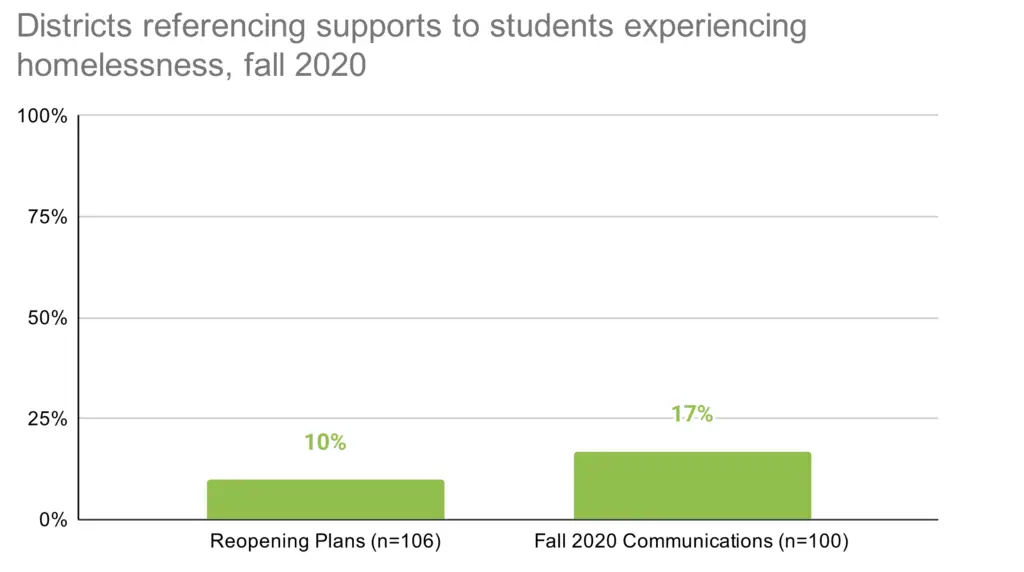

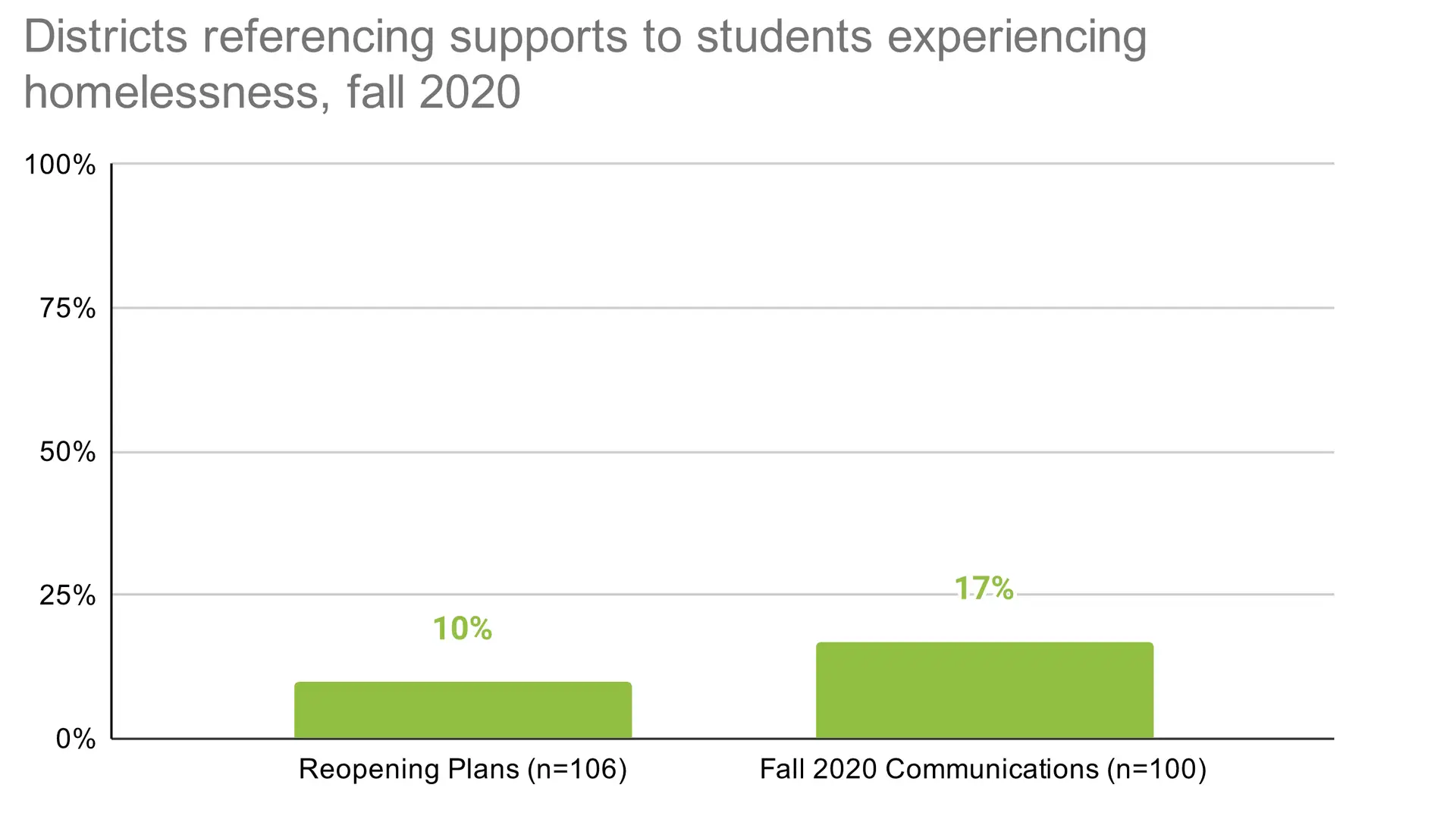

This summer, CRPE conducted a deep dive into the supports districts offered to their students experiencing homelessness. We found that unhoused students were largely unmentioned in districts’ fall reopening plans, with only 10 percent of the district plans in our database addressing homeless supports.

This fall the pattern continued. Just 17 out of 100 districts in the database articulated plans for support tailored to unhoused students during the current school year, signaling that these students are not being prioritized for assistance.

Barriers to student identification result in fewer students being served this fall

Months after the release of initial reopening plans, reports from district McKinney-Vento liaisons—adults tasked under federal law with finding and supporting students experiencing homelessness—indicate that unhoused students are not being identified for support in the first place. SchoolHouse Connection estimates 420,000 fewer students have been identified this year, which is a direct result of school building closures. Under remote learning, families no longer submit transportation requests, which districts often use as the first step in identifying students who are homeless. Without this important source of data on students’ housing circumstances, 41 percent of McKinney-Vento liaisons reported a decrease in the number of identified homeless students.

While school systems are identifying fewer students for support, the number of homeless students has likely increased since the onset of the pandemic. Parents of unhoused students face a daunting choice: choosing between going to work or helping their children with remote learning. Many homeless shelters do not allow parents to leave their children alone while they go to work, which eliminates a potential solution for giving unhoused students a stable place to attend remote classes. Additionally, parents experiencing homelessness tend to have jobs that must be performed in-person with little schedule flexibility, which can prevent them from assisting their children with school while supporting them financially.

Some districts are making identification a priority

Luckily, some districts are making the identification of unhoused students a priority. Mesa Public Schools, in Arizona, requires all staff to watch a training video that describes signs that a student may be homeless, along with an employee reporting procedure. Jefferson County Public Schools, in Colorado, operates a referral program in which staff and the community at large can refer a student to receive assistance from a Community and Family Connections liaison.

Furthermore, several districts have implemented solutions that provide unhoused students with consistent access to wifi and general support. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Schools in North Carolina, for example, transformed five school parking lots into deep zones of wifi for its thousands of students who do not have reliable internet access, along with two mobile wifi centers on school buses. Districts such as Baltimore City prioritized unhoused students when distributing technology devices, while districts such as Los Angeles Unified committed to expanding childcare services in order to give vulnerable students a consistent remote environment while the parents go to work.

Methods to identify students experiencing homelessness in remote learning

Though a number of districts are providing beneficial support for students identified as experiencing homelessness, most are failing to emphasize how they can use new approaches to identify unhoused students during remote learning. While schools have historically relied on transportation data to cue identification, districts in remote learning can instead train and ask teachers to identify students using visual cues.

Taylor Paquette, a McKinney-Vento liaison in New Hampshire’s Nashua School District, provides detailed advice for identifying these students, even in remote settings:

- Frequent changes in the background of where the student is working; the student appears to be changing location frequently

- Many different people in the background, beyond just the student’s immediate family

- Background appears to be in a motel/hotel

- Background appears to be in public areas

- Student/parent unreachable for periods of time

- Difficulty participating in scheduled class times/completing assignments

Many districts have a policy of allowing cameras to be off during remote learning. While intended to protect a student’s privacy, this approach may inadvertently prevent this kind of troubleshooting. Districts should still equip teachers to search for these indicators—especially in one-on-one and small-group settings—in order to more readily identify unhoused students and provide adequate support for their achievement in remote learning.

Targeted funding is part of a national solution

The federal McKinney-Vento Act articulates a commitment that students experiencing homelessness have a right to an education. To ensure the pandemic doesn’t jeopardize these students’ rights, our new administration has a responsibility to ensure districts have both the necessary resources and a clear directive to find and support unhoused students.

In a national survey, only 18 percent of school district homeless liaisons indicated that their school systems were using federal coronavirus relief education funding provided by the CARES Act to meet the needs of students experiencing homelessness. Stimulus education relief plans to date have been broad and largely silent on the urgency of preventing hundreds of thousands of students from losing their access to public education—placing them at greater risk of experiencing economic difficulty and homelessness as adults.

Future federal stimulus packages should dedicate specific funding to the McKinney-Vento Act’s Education for Homeless Children and Youth program—the only federal program that removes barriers to identification, enrollment, and attendance caused by homelessness. But in exchange for additional funding, Congress should require school districts to guarantee they will help educators identify unhoused students, and give these students the assistance needed to access and participate in their education.