Remote learning is no longer an unprecedented mode of delivery for most schools across America. For many students returning to class in the coming weeks, it will be back to school online.

image3-1536×929.png

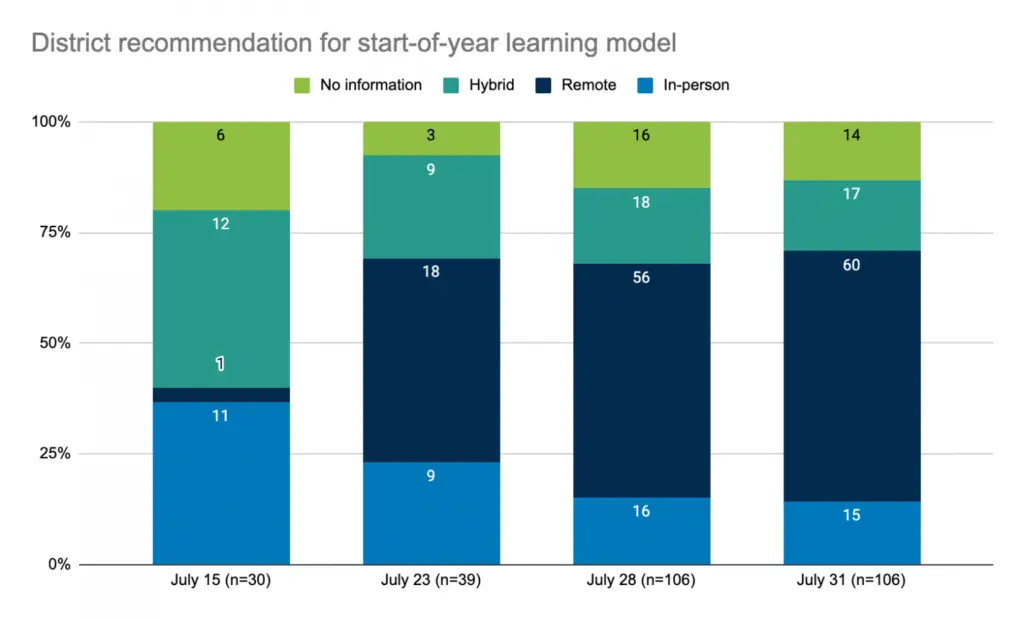

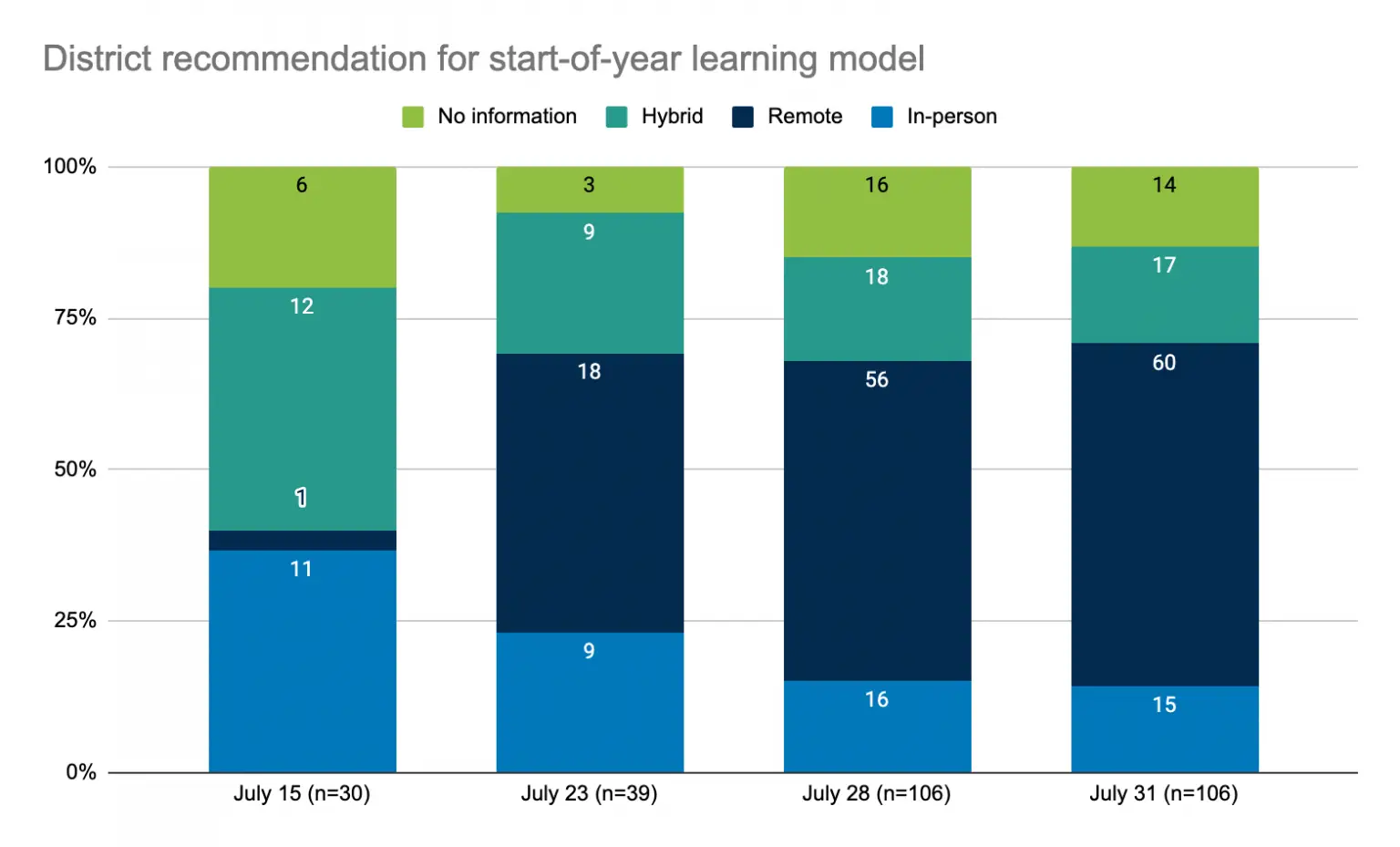

Compared with this spring’s rapid and unplanned transitions from the classroom to the cloud, what is different this time around? We analyzed 86 school district remote learning plans to find out how they are approaching the 2020-21 school year. Our reviews of reopening plans show some promise, with districts commonly committing to offer more live instruction and improved consistency, but little communication detailing check-ins, supports for younger students, diagnostic assessments, individualized tutoring and other evidence-based interventions.

Live instruction is now common

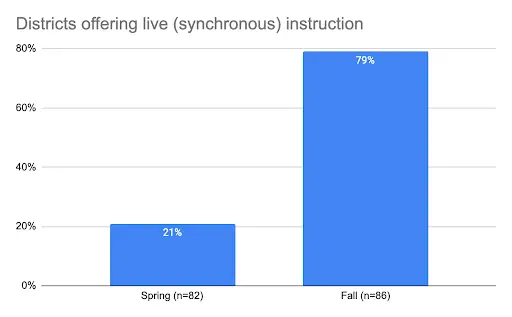

Spring expectations for curriculum, instruction and progress monitoring ran the gamut, but districts are now taking a clearer tone with families and staff. They are responding to parent feedback, primarily by offering more teacher-student interaction and live instruction over videoconference. Of districts reviewed that detail their curriculum approaches, all are providing access to online curriculum. None are providing paper only.

While few of the districts we reviewed (18 of 86, or 21 percent) specify how much instructional time they plan to offer, expected learning time in these districts averages about six hours per day. A few, like El Paso, indicate that they will match traditional school day schedules. Students won’t necessarily spend all of this time receiving real-time lessons from teachers alongside their classmates. But we find a significant uptick in live teaching compared with this spring. Baltimore County Public Schools is the only district reviewed that specifies exactly how much live instruction must be provided. The plan states that students will receive between two hours and 3½ hours daily, depending on grade level, and will then have up to three hours of independent work.

Fall counts based on districts offering only synchronous or a combination of both synchronous and asynchronous instruction.

Districts shifting to virtual curriculum

Families want simpler technology and more consistency across classes. Many districts seem to be responding to that feedback.

Not all have provided details on their anticipated remote curriculum, but this could be because many plans were written around the assumption of starting in person or in a hybrid setting. So far, 87 percent of districts reviewed (75 of 86) have shared information on what remote curriculum they will provide.

Several districts are providing more clarity about learning materials and striving to connect learning experiences across remote and in-person scenarios. Jefferson County Public Schools in Colorado and Oklahoma City Public Schools are directing teachers to always include resources and tasks in their centralized online software — programs such as Canvas or Google Classroom — whether they are teaching remotely or in person. For many districts, the requirement to post all assignments online was previously up to individual teacher discretion or may have been a practice only during school building closures. Now, districts are making more intentional use of these online learning management systems as they aim to provide a seamless transition if students must switch between remote and in-person learning.

Hillsborough Public Schools and Orange County Public Schools, both in Florida, expect teachers to livestream lessons they physically deliver in their classrooms via web conferencing software, such as Zoom, so students learning at home can participate in the same lessons. The Orange County website shares a “day in the life” document to give families a better idea of how this will work in practice. This teaching model is a response to family survey results requesting maximum flexibility in student attendance options, and a compromise between competing demands for in-person and safe-at-home school options.

These strategies support the eventual transition between remote and in-person learning and increase preparation for inevitable sick days and quarantining to come. Coordinating these efforts and communicating them in advance also mitigates disruptions to schooling as health conditions change.

Still guessing on grading and assessments

Despite providing more detailed explanations than in the spring about how schools will teach students, only 36 percent of the 86 district remote learning plans we reviewed clearly stated that they will grade student work this fall. This is fewer than in the spring, when 51 percent communicated this expectation. It is unclear whether this is because of an expected return to “business as usual” or if districts are still figuring it out.

Just four districts said they are revising their grading policy for this school year. For example, Baltimore City Public Schools’ plan calls for 70 percent of students’ marks to be made up by exams, with classwork, participation and homework forming the other 30 percent. In Texas’s Cypress-Fairbanks Independent School District, students will be able to opt out of final exams if they meet certain grade, attendance and participation standards.

Forty-eight percent of reviewed districts made clear that they will track attendance this fall, up from 32 percent in the spring. It is possible that districts’ remote learning plans, still being ironed out, don’t yet include attendance but will by the start of the school year. Some express a renewed commitment to finding and re-engaging students who are not participating in remote learning. Oakland Unified School District in California will triage support for students who are absent three times, even during remote learning. These students will be prioritized for phasing back to in-person learning when conditions allow.

Some states, such as Texas, have allowed more flexibility in how to report attendance. District plans include multiple new ways of counting students in a remote setting. In the Houston Independent School District, students who engage in virtual learning and submit assignments by specified daily deadlines are considered present. Students must attend 90 percent of the school year to receive credit and be promoted.

Overall, districts are not communicating graduation criteria to students and families, though 90 percent of states are keeping graduation requirements the same.

Less information about diagnostic assessments and progress monitoring than anticipated

Only 29 percent of districts reviewed (25 of 86) mention diagnostic assessments in their reopening plans. This lukewarm emphasis is true at the state level as well, with only six states making this a requirement for their districts.

With most districts planning to administer diagnostics in person in the first weeks of school, it is unclear how, if at all, they will assess students in remote settings. Effectively figuring out every student’s current strengths and weaknesses off-site introduces new remote challenges around test security and data reliability.

Less than a third — 29 percent — of districts specified how they will support students academically while keeping them on pace with their grade level. Few districts stand out as employing examples of evidence-based strategies, such as tutoring (just six of the districts reviewed reference tutoring), but some are taking creative approaches to scheduling in order to provide individualized student supports.

Tulsa Public Schools introduced weekly distance learning days and six academic “intersessions” to give schools flexible time for targeted tutoring. For elementary students, Georgia’s Cobb County School District has a sample remote learning schedule that builds in morning meetings, art, music, live instruction for core courses and time for independent work, small groups and content delivered in multiple ways to reach a range of learners every day. The district reserves Wednesdays for targeted interventions.

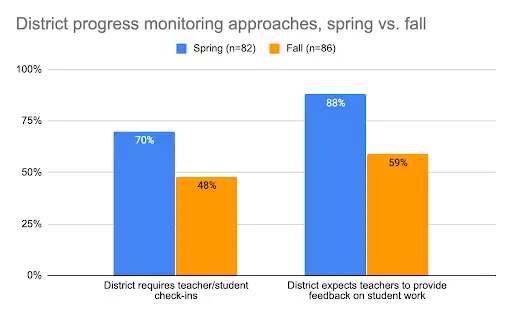

About half of the districts we reviewed (42, or 49 percent) specified how they plan to monitor academic progress throughout the year. Less than half (41, or 48 percent) expect teachers to regularly check in with their students. This is noticeably fewer than the spring, when 70 percent of districts set this expectation. Similarly, fewer districts expect teachers to provide feedback on student work than did in the spring (59 percent versus 88 percent).

This drop could be due to districts’ assumption that more live instruction will replace individual check-ins and feedback. Or it may be that remote learning plans are still too nascent. But it is not yet clear whether or how students will get 1:1 time with their teachers or individualized feedback on their remote work.

Check-ins and feedback on work are standard progress-monitoring methods that must be guaranteed in the new school year. In the spring, many districts had large numbers of chronically absent students. Lack of engagement was often higher for students of color and other vulnerable populations. Strong relationships between students and teachers, as well as check-ins and feedback on work, are likely critical ways to increase student engagement and attendance.

Districts still unclear on how to effectively educate elementary students remotely

Elementary school children received less instruction and had less access to summer school than older students. A small number of districts have prioritized more in-person instruction for these students (18, or 21 percent) in their fall plans.

Some, like Duval County Public Schools in Florida, are giving elementary children more days than middle or high schoolers. Others, like Guilford County Schools in North Carolina, will teach K-8 students in person and have asked high school students to go fully remote. Guilford has also strengthened accelerated online learning for juniors and seniors through an extended dual-enrollment program with local universities. Henry County Public Schools, in Georgia, emphasizes early learning and is exploring serving first-graders four days per week while the rest of the students learn remotely.

Still, it’s not clear how the majority of districts will support remote learning for the youngest students. For example, Charlotte-Mecklenburg is providing iPads to all its K-2 students but has no explanation yet for what remote learning will look like for them. Last week, the district canceled plans to hold in-person introductory meetings for students and teachers to learn technology and build rapport.

In California’s Sacramento City Unified School District, students in transitional kindergarten up to third grade will receive about two hours of real-time instruction and two hours of assignments every day, with whole-group lessons recorded and stored so students who cannot join can watch later.

Parents and students are counting on districts to get remote learning right this time

Students cannot afford for fall remote instruction to go poorly. Parent and student surveys made clear that they expect and need districts to do better than this spring. With the growing likelihood that students in most districts will not return to their physical schools this fall, districts must resolve a number of important issues.

While there are many examples of creative thinking and progress in remote learning plans in preparation for the fall, many critical details are still not in place. We suspect this is because districts put a great amount of detailed planning and attention toward their hybrid in-person plans, which they had to put on hold in the last-minute shift to fully remote learning. In those plans, many districts called for in-person supports for the most vulnerable students, the youngest students or those who faced the biggest learning gaps in the spring. These are the children who can least afford for school systems to repeat their mistakes. Districts must create and deliver clear plans to support them, and all students, in what promises to be a very challenging year.

This post originally appeared in The 74.