Imagine a time traveler from 1924 arrives in 2024. She’s overwhelmed by how the world has changed, from ubiquitous smartphone use to widespread vaccine access. Then, she steps into a typical school, and she’s confused. While the kinds of jobs Americans work in are barely recognizable to her, classroom learning still feels much like it did in her time. While access to schools has expanded dramatically, she learns that educational outcomes are consistently predictable by factors like race, income, and disability status. And while most of the world returned to normal after a pandemic swept the globe, she hears that students and teachers still struggle to recover after the disruption.

But glimpses of a better future of schooling are emerging across the country. Since 2018, the Canopy project has been cataloging where and how schools are working to design equitable, student-centered learning environments. To date, 753 schools have been nominated for the project, and 310 are searchable in the Canopy database. Their innovative practices—from competency-based learning models to restorative approaches to discipline—reimagine the systems, structures, and instructional core of “school.”

We’re often asked: are these schools delivering better student experiences and outcomes? How do we know?

A few months ago, the Canopy project published a new report with early answers to these questions, and the results are both exciting and sobering. They suggest that Canopy schools’ focus on non-traditional outcomes doesn’t appear to come at the expense of success on standardized tests. However, they also shed light on profound challenges schools face in gathering and sharing evidence of their impact on those broader outcomes—challenges that could be solved with more investment from policymakers, funders, and researchers.

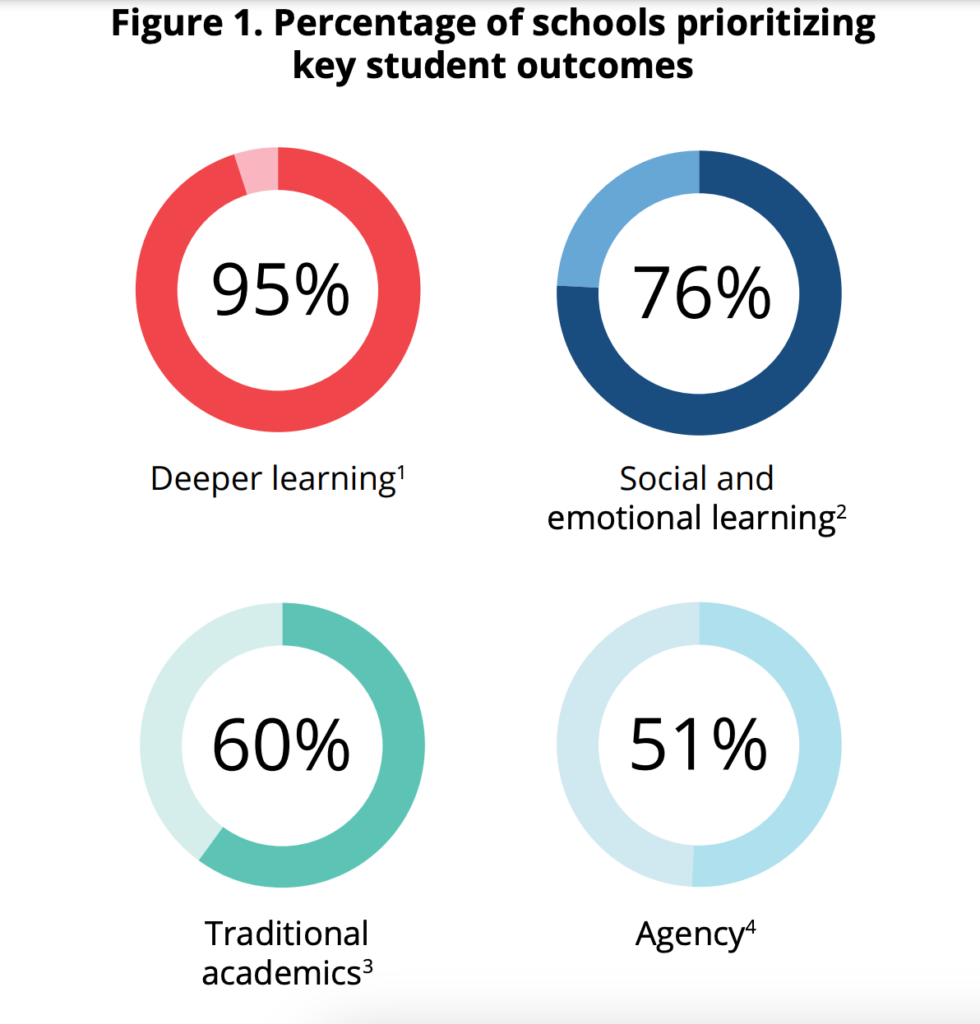

We found that Canopy schools prioritize a broad range of non-traditional outcomes. For example:

- 95% prioritize deeper learning in which students apply core academic content to relevant and authentic real-world problems

- 76% prioritize social-emotional learning (SEL)

- 51% prioritize agency, which we define as the capacity for students to set a goal, reflect and act responsibly to effect change, and play an active role in deciding what and how they will learn

Our analysis suggests that these goals don’t come at the expense of success on traditional academic indicators. Our team used a statistical modeling technique known as heteroskedastic ordered probit (HETOP) modeling to compare Canopy schools’ standardized test scores to the scores of demographically similar peer schools. While they faced some data and methodological limitations, their analysis suggests that Canopy schools perform more or less similarly to their non-Canopy peers.

Unfortunately, only a small fraction of Canopy schools could generate evidence of their impact on non-traditional outcomes. This may be because educators are typically left to solve the problem of measuring impact independently with very little help from outside their schools. When we asked Canopy leaders about the source of their innovative assessments, more than three-quarters said they created them themselves. We shouldn’t be surprised that they struggle to systematically gather and share evidence of impact. As Donnell Cannon, Executive Director of Maureen Joy Charter School and a Canopy project advisor, recently noted in a conference presentation, classroom educators and school administrators can’t be expected to spend their nights and weekends building new high-quality assessment tools from scratch.

If policymakers, funders, and researchers are serious about accelerating innovation, they need to prioritize helping educators gather and share evidence of the impact of those innovations. Specifically, schools need:

- Tools to measure outcomes they care about. Some of these might be tailored to a school’s specific approach. But, since many innovative schools prioritize similar outcomes, it’s easy to imagine them adopting similar tools to gather collective evidence. The Mastery Transcript Consortium, Ednovate’s Whole Child Report Card, and Transcend’s Leaps Student Voice Survey offer examples of these types of tools.

- Accountability policies that provide space for innovators to gather a broader range of valid evidence. While some states—like Colorado, Kentucky, and New Mexico—are experimenting with accountability systems beyond standardized tests, all are still forced to operate within a federal mandate of annually assessing every student in literacy and math using statistically comparable measures. How much innovation could be unleashed if accountability systems balanced standardized assessments with more innovative, locally-designed measures?

- Infrastructure to help them organize and communicate their impact to the public. This could be provided either by state education agencies or third-party organizations (like the Canopy project or GreatSchools.org) dedicated to sharing information about schools.

The Canopy project demonstrates that innovation is happening all across the country, that innovators care about a broad range of student outcomes and experiences, and that innovation doesn’t need to come at the expense of performance on traditional academic measures. However, educators are caught in a Catch-22 as policymakers and funders demand evidence of impact without investing in the tools, policies, and infrastructure that would help generate this evidence. Accelerating the future of schooling requires policymakers, funders, researchers, and other ecosystem actors to invest in innovation with the same level of dedication and urgency as the innovative schools in the Canopy.

Teachers Want to Innovate—Schools that Don’t Let Them are Losing Out

Chelsea Waite

Principal, CRPE