Artificial intelligence (AI) is evolving at lightning speed, but will U.S. classrooms be able to evolve with it—and take advantage of its potential benefits? A new report by the American School District Panel (ASDP), a research partnership between the RAND Corporation and CRPE, gives an early look at how AI is influencing teaching and learning, as well as what the future may hold for its role in American classrooms.

The bottom line: AI has little presence in US classrooms today, but that is likely to change soon. The question is, who will benefit? Our study shows early signs that more advantaged suburban school districts are ahead of urban, rural, and high-poverty districts in terms of AI use. This should be cause for concern for those who want to see the benefits of these technologies reach the students most in need of help—and it should spur policymakers and philanthropists to start taking more assertive action.

Major findings: AI in the classroom

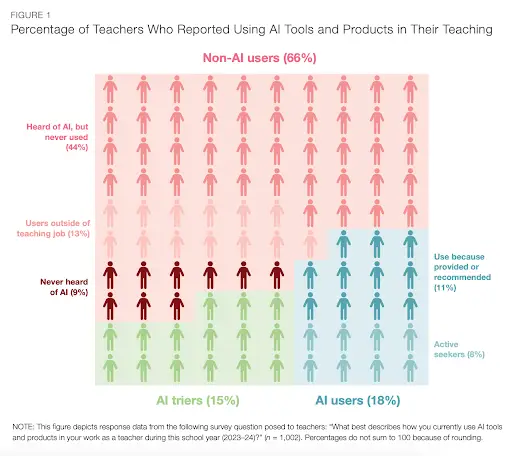

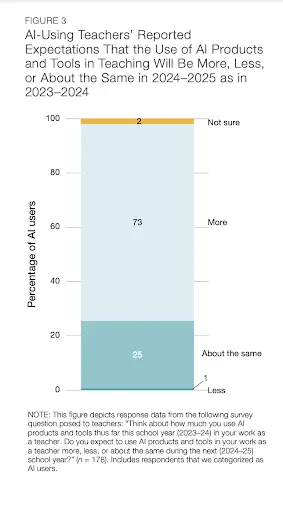

One of the most striking findings from our report is that as of Fall 2023, just a small portion of a nationally representative sample (only around 18% of K–12 teachers nationwide) reported using AI for teaching. A small subset of those early adopters (8%) consists of what I would call “super users:” teachers who are excited about the potential use of AI in classrooms and are staying current with the latest tools by actively experimenting with uses for AI in their profession. I follow some of these super users on social media, and they are coming up with creative and exciting ways to save themselves time while making learning more engaging and personalized for students.

These early adopters predominantly teach middle and high school students, particularly in subjects like English language arts and social studies, which I suppose is not too surprising, given that generative AI is advancing most quickly on language and visual models.

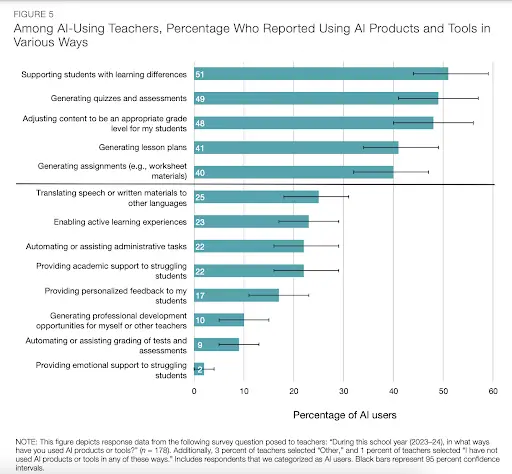

Teachers report using AI primarily via the major virtual learning platforms and systems that have been around for a while like Google Classroom, iReady, and IXL. However, 50% of teachers who report using AI in the classroom are using generative AI chatbots, like ChatGPT. A much smaller percentage of teachers are active on more specialized AI classroom tools that provide customized tutoring (e.g., Khanmigo), lesson plans, and assessment generators (e.g., Education Copilot and PrepAI), or automated coaching and feedback to teachers.

Educators report using AI in a variety of ways, but teachers are mostly likely to say they use AI to support students with “learning differences.” It may be that AI is simply making current teacher practices easier or faster. For example, a teacher might use AI to easily create customized homework for a student to practice a concept they were struggling with in class. Teachers may also be using AI to allow a student who reads at a grade 4 level to access high school-level social studies content. However, these fairly common instructional strategies do not necessarily accelerate student progress. Understanding how teachers use AI to help students who are struggling or have disabilities, and how effective it is, are open questions that should be studied soon.

There are positive approaches to AI policy, but existential concerns loom

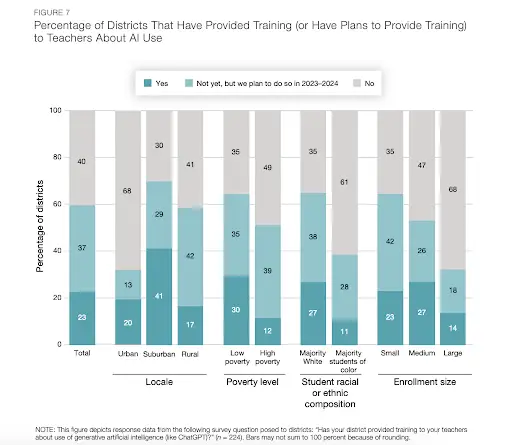

While there have been several high-profile cases of school districts banning AI, our survey results and interviews suggest that most school districts are interested in exploring the positive potential of AI. Twenty-three percent (23%) of districts had already provided training on AI, and another 37% intend to do so at some point during the 2023–24 school year. Furthermore, the district leaders we interviewed were more focused on how to support teachers in using AI to make their jobs easier than on how to block AI use among students or staff. They recognize AI’s potential to make teaching easier but worry about how to bring teachers up to speed quickly.

One leader in a midsized district said, “My personal concerns are that it will not be operationalized evenly in classrooms. It’s just like curriculum. It’s hard to get curriculum consistency, and it will be the same with AI.” Another leader in a small district similarly remarked, “I’m more concerned that there’s a fear of it … This is something that if you don’t embrace, you’re just going to be doing extra work.”

Districts have good reason to focus on training and educator support. Teachers report that some of the greatest barriers to their using AI in classrooms is lack of school or district guidance and professional development.

Teachers’ and district leaders’ concerns about AI use seem less about school-specific applications and more about student privacy, potential bias in AI, and the impact of AI on society in general. The district leaders we interviewed tended to believe that cheating and plagiarism concerns could be covered under existing district rules. They did, however, express the need for more policy guidance from trusted sources, like school board associations or respected local school districts, and noted that developing policies around AI is especially difficult due to the technology’s rapidly evolving nature.

Worrying signs: AI could exacerbate educational inequality

Our study points to early signs of faster uptake of AI in more advantaged settings. Suburban, majority-white, and low-poverty school districts are currently about twice as likely to provide AI-use training for their teachers than urban or rural or high-poverty districts. Advantaged districts are also more likely to have plans to roll out training in the coming school year.

This is just the beginning

The majority of teachers surveyed (60%) have either tried AI and set it aside or never heard of it. But while uptake is minimal now, things could change rapidly. Both users and nonusers say they plan to use more AI tools for teaching in the near future.

If we hope to help teachers realize the positive potential of AI, understand AI’s impact in classrooms, and ensure that the kids most in need of solutions get them, then we must take action. This is not an issue that can wait for years of committees or strategic plans in policy or philanthropic circles.

CRPE’s initiatives: Examining AI in education

Our findings raise many critical questions. If there are benefits to using AI in education, then they look likely to accrue to more advantaged kids.

- How can investments and policies ensure these benefits reach the students most in need?

- How will so many districts train up their teachers amid other pressing priorities and increasing financial constraints?

- How can educators learn quickly about which AI tools and strategies work best?

At CRPE, we are deeply engaged in trying to help answer these questions by understanding and shaping the impact of AI in K–12 education. We are committed to leading the way in this important work, ensuring that AI becomes a tool for enhancing learning and equity, rather than exacerbating existing disparities. We are tracking and reporting on state regulatory moves. We are conducting a study of school districts that are implementing AI at scale to identify best practices and potential pitfalls. Additionally, we are examining “first adopters” of AI among educators and districts, aiming to understand how early experimentation with these technologies can inform broader adoption.

To address the broader policy issues around AI in education, we are convening education and technology leaders to discuss the ethical, practical, and pedagogical implications of AI integration in schools. These efforts align with our commitment to innovating for educational equity and excellence, ensuring that all students benefit from technological advancements.

No more navel-gazing: Quick action is imperative

The future of AI in K–12 education is bright, but also fraught with challenges. The findings from the recent RAND report underscore the need for thoughtful and proactive policies, as well as professional development to guide positive AI adoption in schools.

There is an urgent need for much faster and more comprehensive teacher training. Urban and rural districts, in particular, will need access to high-quality professional development and should not be left to develop those capacities on their own. The U.S. should consider a national teacher-training effort, akin to what countries like South Korea and Singapore are doing. Training should focus on helping teachers use AI to address learning needs and accelerate learning. A highly targeted research effort should focus on assessing the efficacy of such interventions and studying barriers to effective implementation and how they are being overcome.

While AI presents both risks and rewards, one thing is clear: AI has already arrived in U.S. classrooms. If state and federal policymakers persist in providing insufficient support for students, teachers, schools, and systems, they risk widening inequalities and missing opportunities to prepare students for a rapidly-evolving future.