As students and teachers begin the new school year, what learning will look like this fall is now in focus. One thing is clear: The opportunity gap for students living in poverty is likely to be wider than ever.

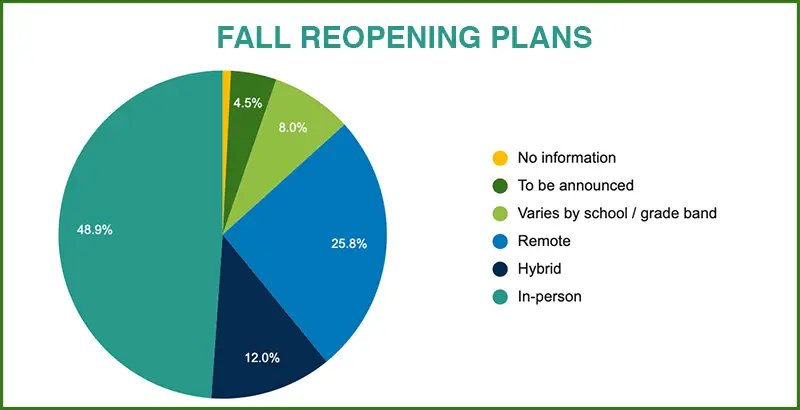

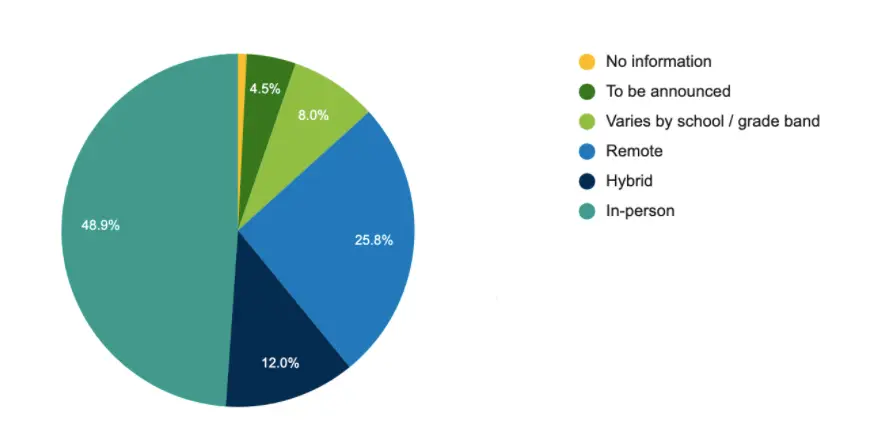

Our recent review of a nationally representative sample of 477 U.S. school districts estimates that about 26 percent are opening fully remote.

Fall Reopening Plans

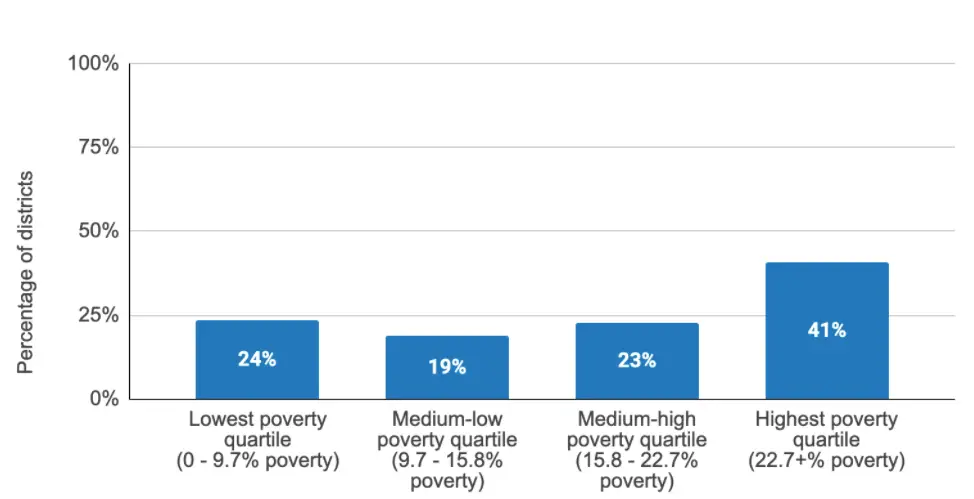

Critically, we also estimate that among the districts serving the largest number of students in poverty, 40 percent are opening fully remote.

Percent of Districts Opening Fully Remote by Poverty Quartile

As a result of this pandemic, many students who have historically faced opportunity gaps in our schools will further be denied access to the resources and experiences they deserve.

Remote learning has been difficult for many students, families and educators. Children living in poverty face particularly steep barriers. Even after the spring push to equip students for remote learning, a July survey found that 14 percent of households earning less than $25,000 a year did not have reliable internet access.

In part as a result of chronic stress and its impact on the brain, students living in poverty learn best when they have trusting relationships with educators, safe environments, a sense of control, and teachers who have the time and space to attend to key emotional skills and needs.

But relationships, trust and a sense of safety are hard to establish by videoconference. A sense of control can vanish when servers crash, internet connections cut out or students can’t log into assignments. When these basic conditions for learning are not available, teachers say, many students are likely to log off or disengage.

Persistently high COVID rates mean it isn’t safe to return to in-person instruction in many communities, and parents — particularly lower-income parents — remain wary of reopening schools. Lower-income adults are four times as likely to believe they will die from the virus than affluent adults, and these worries are well-founded. A recent survey found that 57 percent of parents in households earning less than $25,000 supported restarting the school year with remote learning.

How to protect learning opportunities while learning remains remote

It goes without saying that any household without internet access must get it — whether through arrangements with providers or mobile hotspots, and whether this is facilitated by the district, the city or another community partner. State and federal leadership is needed. School districts like Baltimore City Public Schools are absorbing six-figure broadband bills for families in need, bills they might not otherwise be able to afford.

Districts should prioritize live, real-time engagement between students and teachers and stay diligent about contacting students who aren’t showing up. Videoconference classes can be difficult to organize and sustain, but live engagement is important to students (and their parents). “Nudging” strategies, such as text messages and phone calls, can help boost attendance and participation. Many districts used teacher-student check-ins to reconnect with children who were disengaged in the spring.

Reaching out to students who miss even one session can help resolve any issues keeping them from engaging in school before learning veers off track. Some students fell completely off their districts’ radar this spring, and they can ill afford the same gaps this school year.

Districts and communities could also consider ways to expand the number of people who can support learning. Examples are emerging across the country — even in districts that struggled with remote learning in the spring:

- Los Angeles Unified School District partnered with an external volunteer program to tutor students after school and on weekends. During the school day, instructional aides and substitute teachers will provide small-group instruction for struggling students.

- Nevada’s Clark County School District has a plan for school-based teams of licensed professionals to conduct regular wellness check-ins with each student and family. These will assess academic, social-emotional and health needs.

- Baltimore City is teaming up with the University of Maryland to match university students with ninth-graders who were struggling with remote attendance for mentorship and academic support.

Prioritize help for students most in need

Where it is safe to consider some in-person learning, schools should prioritize the students most in need of that kind of support. Our recent review found that only about 29 percent of districts plan to prioritize any groups of students for in-person instruction when possible to do so. That shrank to 23 percent among districts in the highest quartile of poverty.

These districts are offering or plan to offer some in-person instruction to students who are, for example, experiencing homelessness, do not have reliable internet access or have Individualized Education Programs that require in-person support. Districts and community partners are creating district-run pods or community hubs for some students to assist with remote learning. These efforts can help ensure that support is available for students who most need it.

We collected our data in late August, and district plans continue to shift by the day. Many districts that are starting with remote learning plan to move to some in-person instruction when possible. But the only thing that’s certain about the year ahead is that conditions will continue to change.

Students in the highest-poverty school systems can’t afford to wait for instruction to go back to “normal.” In many cases, “normal” wasn’t working well anyway.

Instead, we need to build new systems and strategies to connect students with the resources, opportunities and support they need now, and commit to providing equitable opportunity as we move through, and eventually beyond, the pandemic.