The debate over how schools should teach about race heightened this week when the College Board released a framework for a new Advanced Placement course in African-American studies that reduced some of the content from a pilot version — content supported by hundreds of Black scholars and progressives but criticized by prominent conservatives.

The national fervor over the content of a new AP course is a little unusual, but the course is essentially setting a national standard for advanced instruction and materials about Black history and modern race issues. Our timely new report on political polarization in local schools identifies the extent to which districts are struggling to manage the controversy over teaching of race and racism — and helps explain why the new AP Black studies course has landed in boiling water.

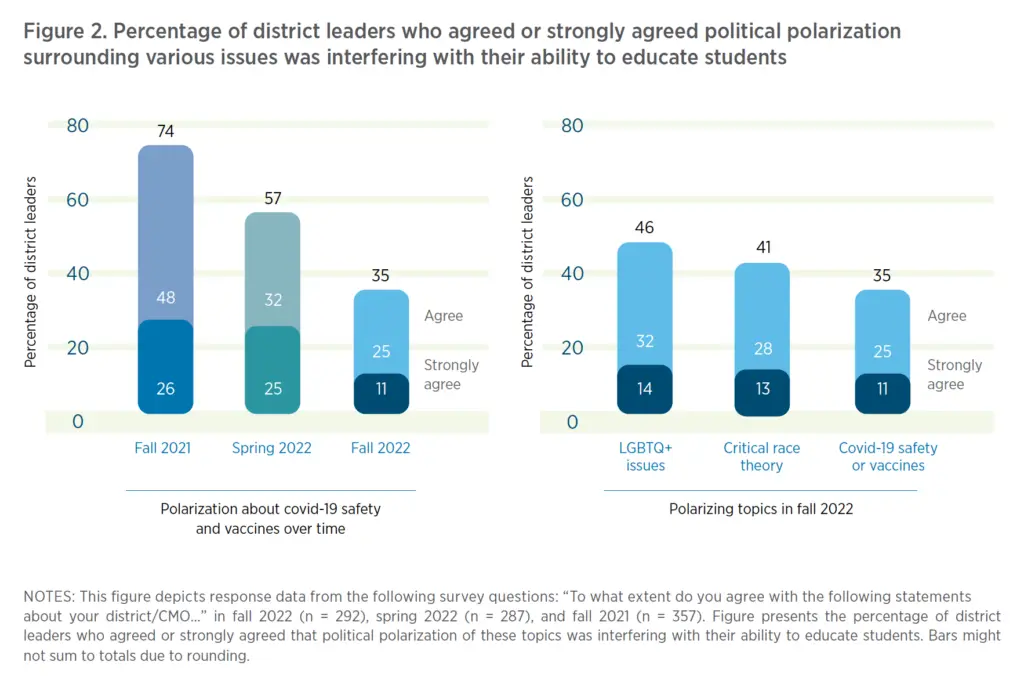

For example, more than 40% of U.S. school district leaders this fall said political polarization around critical race theory was interfering with their ability to teach, according to our research, which was conducted with RAND and based on surveys and interviews with school system leaders.

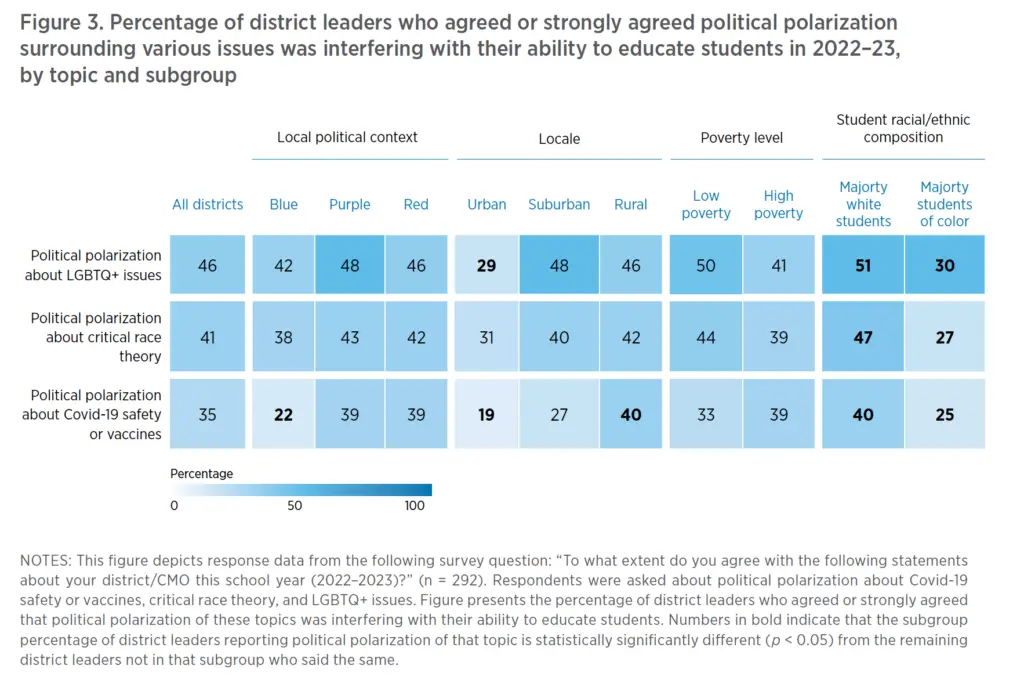

The problem is often more acute in majority white districts. There, almost half of leaders (47%) said local controversies around how to teach about race and racism were interfering with teaching as of fall 2022 (note: our researchers asked about polarization around CRT, specifically).

Worse: 4 out of 10 leaders of suburban districts, wealthy districts and majority white districts said their educators or school board members had received verbal or written threats related to controversies over CRT, Covid-19 safety, and gender identity.

LEARN MORE: Join CRPE and RAND researchers on Tues., Feb. 7 from 3-3:30 PM EST for a virtual discussion about how district leaders and teachers are handling political polarization and restrictions on teaching controversial topics.

However, we don’t have to sit back and watch neighborhoods implode over these issues. Many district leaders described how they’re addressing community concerns and limiting the negative impacts of political controversies on classrooms. And most — 2 out of 3 district leaders — did not do so by eliminating or reducing instructional content.

Yes, one-third (32%) of leaders did pause or change one or more subject service areas we asked about. Social-emotional learning, health and sex education, or mental health services were frequent targets, according to our research.

District leaders who changed instruction also said they were sometimes motivated by state directives limiting controversial topics. Such directives have been on the rise; 44 states have introduced bills or taken steps to limit how schools can teach about racism or sexism since 2021, according to a tracker by EdWeek magazine.

A few district leaders reported more drastic moves: One eliminated discussions of elections; another referenced scrubbing the curriculum of controversial topics altogether.

But more leaders from all districts — urban, suburban and rural — described other ways of successfully quelling the controversies, including:

- Creating new policies and procedures related to teaching controversial content, such as having teachers notify parents of upcoming material, or creating a process to work through reviewing library books

- Regularly meeting one-on-one with the parents raising concerns

- Making it clear that parents could opt their children out of instruction

“We have addressed the ‘whispers’ we hear about the issues to avoid hearing ‘screams,’” one district leader told our researchers, when asked about heading off controversy.

From where we sit, it’s clear administrators and school board members need more preparation for the increased political demands of the job. State departments of education and school board associations could and should provide training for prospective board members about their responsibilities and the consequences of increasing polarization. We applaud North Dakota, for example, for using federal stimulus dollars for a new institute to support better school board governance.

Schools will always have to navigate political challenges. But when residents threaten educators and flood district offices with mountains of record requests or names of books to ban, it erodes public trust and sours relations between schools and communities — the very entities that should be working together to help children learn.