This is the first in our series of “Notes From The Field” on personalized learning.

My colleague and I recently visited a middle school science classroom. Students, outfitted with safety glasses, were organized into groups of three to four. The room was lively but not disorderly as each group worked on its own experiment. As we walked the perimeter of the room, we saw many of the hallmarks of a personalized learning (PL) classroom: small groups worked independently, each worked on an activity that they had chosen, the teacher engaged with small groups of students.

But when I asked a group of students about their project, I learned that their task was to mimic the rising and setting of the sun using a light bulb and tray of sand. They were asked to compare the temperature of a tray of sand with the light bulb turned on or off and consider the implications for the surface temperature of the earth.

These students knew exactly how this experiment would pan out before they even started.

The teacher worked hard to get the day’s lesson off the ground. She did what all good PL staff development tools advise. She mapped out and prepared several different lab assignments from which students could choose. She trusted her students to choose their partners and their activities and to be productive in their work. As she worked with students in the class she deftly switched between the different activities students were working on. But, at the end of the day, the learning goals and activities were far below the level of understanding and reasoning capacities of these students.

Many teachers in the PL schools we’ve visited are making big changes to their classrooms, as the teacher in this example has. Gone are the rows of desks that we usually find in typical classrooms. In their place, teachers are creating spaces where students can engage in a variety of learning activities, often working at their own pace, sometimes working on a computer. Countless teachers have shown us how they are rewriting their lesson and unit plans to give students more chances to direct their own learning. And teachers have talked to us about how they are rethinking their assessments to better reflect deep learning goals.

But we’re also seeing that it’s easy for schools caught up in these sweeping changes to lose sight of what will really push student learning forward: high-quality, challenging, rich content.

Like many traditional schools, those attempting PL are still figuring out what it means to work with Common Core-caliber content and skills (for example, engaging with complex texts in ways that deepen understanding). Like many teachers in more traditional schools, we’re seeing teachers in PL schools who need help understanding and vetting the texts and software they give students—as well as help with strategies to productively engage students with the material. There is serious risk, however, that the demands of tackling the iconography of PL (student groupings, project-based learning, etc.) is crowding out time and energy for teachers to create rigorous content and learning experiences for students.

Can districts and external partners support both rigor and personalization? This may be the most critical and least attended-to question for the successful implementation of personalized learning.

Some schools have managed to achieve the two goals effectively by using these common sense strategies:

Start with standards, not structures. Teachers in schools or districts that started their PL initiatives by focusing on Common Core-aligned, competency-based standards seem to be homing in on rigor more readily than those whose schools or districts started by focusing on personalization structures (like launching a station-rotation model where students move from one learning station to the next). They focus first on planning challenging learning objectives and assessments and let everything else flow from that. For example, in one district we visited, the teachers want students to become adept at recognizing when and how to apply a simple concept, like the Pythagorean theorem, to a complex problem such as an architectural design. Textbook word problems weren’t getting the job done. A small number of pilot schools in this district are now exploring whether personalized approaches and strategies—particularly project-based learning and providing students with more flexibility in crafting their projects—could better expose students to complex problems and better motivate them to persist through complex tasks. How these schools organize their students throughout the day and the activities they engage students in are a means to an end rather than an end in and of themselves.

Assess and discuss rigor. Teachers in the PL schools we visited are clearly hungry for feedback. But too often, the principals, central office leaders, and external partners visiting their classrooms focused on “what was happening” instead of focusing on the quality and rigor of student work. We see a clear need for more systematic feedback that focuses on both instruction and content in their classrooms; school systems could train teachers and leaders to do just that. Student Achievement Partners’ Common Core-aligned Instructional Practice Guides are one example of a flexible tool that teachers and leaders could use to help keep rigor part of the conversation as they reimagine a more personalized and engaged classroom for students.

Personalized learning will not help students if they are working with content that is below their capacity. Rigor and personalization need to go hand in hand.

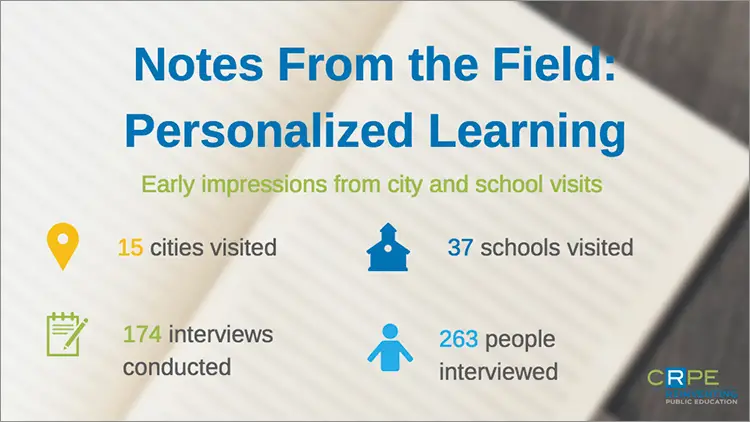

In 2015, CRPE kicked off a multi-year, multi-method study of systemic efforts to support schools implementing personalized learning. We’ll produce a formal report at the end of the nearly two-and-a-half-year project. But in an attempt to give educators more immediate feedback, we’re trying something new in this “Notes From the Field” series. We’ll share noteworthy anecdotes and early impressions from our school visits; these posts should be taken as initial observations from informed and thoughtful partners. We hope these more informal dispatches help launch productive conversations and reflection. Please reach out with your own observations and feedback on Twitter. Find us here: @CRPE_UW, hashtag #PersonalizedLearning