For Black children, the public education system is like a dirty fish tank. They’re swimming in toxic conditions like discriminatory discipline and low expectations.

But before the water can be treated, those students need to be moved to a clean bowl where they can live and breathe. Then, it’s time to clean out the tank.

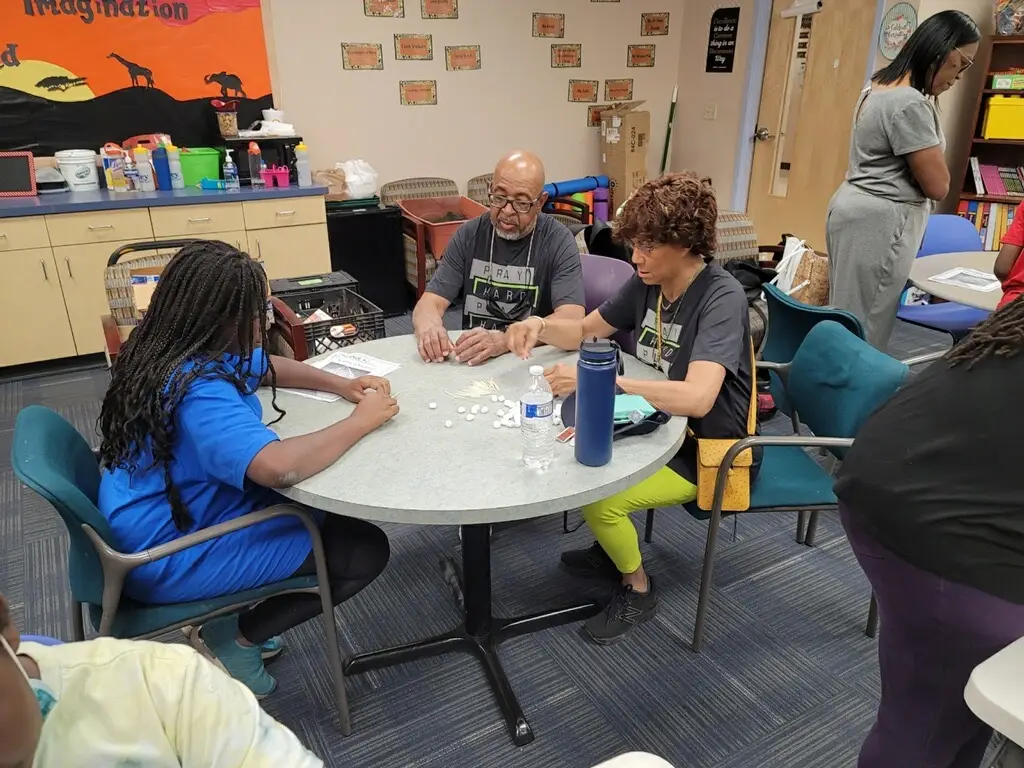

Janelle Wood, co-founder of the Black Mothers Forum, used that analogy to describe the inspiration for her organization’s network of Arizona microschools, which emerged at the beginning of the pandemic.

Activists and entrepreneurs like Wood are creating alternatives for Black students to learn outside the existing public education system, but they ultimately want environments where all students can thrive. And that means taking on the system, which will continue to serve the majority of students.

‘Wood hopes her schools can show educators in other schools what’s possible. But first, they need a hard reset.

“We’re going to have to do some cleaning out of old behaviors and antiquated mindsets” held by education leaders who “don’t understand what it looks like to be culturally responsive” and who believe “the Black parent, the Black teacher, doesn’t know what they’re talking about, and just get in line,” she said during a virtual discussion of Black-led learning environments that CRPE hosted in November.

The discussion was prompted in part by a CRPE study of pandemic pods and microschools that found families of color were twice as likely as white families to say their child was happier and more well-adjusted in their pod than they were in school before the pandemic.

The leaders and educators who participated agreed on the need to do two things: Support efforts to build alternatives outside the existing public education system, and, at the same time, work to change the system itself.

Too often, efforts to create new and better education experiences neglect one part of this strategy. Either they foster alternative environments but ignore the broader system, or they tweak inside the system but remain closed to the breakthroughs that can only be created outside of it.

Chris “Citizen” Stewart, the CEO of Brightbeam, a network of education activists, echoed the need to “put our children into safe harbor so that they aren’t like tea bags being dipped in white supremacy constantly.” As moderator, he asked the panelists whether transformational efforts in small niches can change systems more broadly.

Lakisha Young, co-founder of The Oakland REACH, a California parent organization, said they can. Her organization’s strategy evolved from providing out-of-system solutions to changing conditions inside the Oakland Unified School District. In the first months of the pandemic, REACH quickly started an online hub to deliver summer instruction in math and literacy, and to support students and families the following school year.

After schools fully reopened, the organization pivoted. It’s now focused on recruiting and training parents to work in public schools as tutors. The instruction initially delivered through the hub proved that high-quality literacy and math support could be provided by parents and community members, and test score gains showed the approach could lift academic outcomes. But since most of the students in Oakland will remain enrolled in district schools, the organization needed a way to reach them.

“We started outside of the system, but we’ve moved our work back into the system because some of our most vulnerable kids are there,” she said.

Shifting power to include ideas, approaches of Black leaders

For Black educators, the need to invent outside the system is nothing new.

“The early pod school was the slave cabin,” said Robert S. Harvey, president of FoodCorps and a scholar of Black educational self-determination. Subsequent generations built on that tradition, like the creators of The Mississippi Freedom School and the learning pods organized by the Black Panthers — and now by entrepreneurial educators like Wood and Young.

“It’s a re-imagination and an extension of what Black emancipatory folks have always had to do, which is think at the margin of the education system,” Harvey said.

Maxine McKinney de Royston, a professor at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, is also influencing her school district from the outside in. Her personal experience with pods during the pandemic inspired a microschool she helped launch within the Madison Metropolitan School District.

The pandemic and the country’s nascent racial reckoning are starting to shift power dynamics in public education in two ways, she said. More parents are seeking alternatives outside the public education system. And those who stay are more emboldened to demand equal treatment.

“We pay for them,” she said of the relationship between public schools and Black families. “We staff them. We send out children to them. At some point they actually need to serve us.”

But at present it is not easy to build alternatives outside the system. Wood’s microschools in Arizona operate as subcontractors of an existing online school. This allows them to receive public funding for students who enroll. Other families can pay microschool tuition using the state’s education savings account program — for which the Legislature recently approved a major expansion.

But this sort of arrangement isn’t possible in other states, and public funding isn’t the only policy barrier. Allowing microschools to grow and accommodate all students will require changes to rules governing school transportation and education facilities. Wood’s microschools had to seek help from local restaurants to provide lunches, since they did not qualify for the federal school nutrition program.

These barriers create a risk that innovations outside public education could become a luxury good, reserved only for families who can afford to pay for them and forgo additional services their students receive in public schools.

Education does not exist in a vacuum. Harvey said a policy agenda designed to give families more choices for their child’s education will not succeed without improving their ability to access these choices.

“I can’t be self-determined and be poor,” Harvey said, advocating for policies that also address poverty and economic mobility.

But even if all parents can access learning environments outside the public education system, the fact remains that the system — which serves most children — must learn to clean its water, too.

Efforts like these are, “a beautiful way to think about moving from stereotyping Black children as the problem and start thinking about what can we learn from Black children to create a system that allows them to thrive,” McKinney de Royston said. “Because if we allow Black children to thrive … then all children actually do better.”

Watch the full discussion or read the transcript.