This blog is part of a three-part series profiling school systems that have been implementing workforce innovations or strategic school staffing models for several years.

Through innovative and strategic school staffing solutions, efforts to reimagine the teacher workforce have grown over the past several years. This is in response to prolonged teacher shortages and consistently low retention numbers for new teachers. Despite some worries that strategic school staffing is incompatible with collective bargaining, some school systems are working with their teachers unions to break the mold of the teacher role.

Strategic staffing solutions, like all systemic innovation in schools, require leaders to put forth continuous effort. Including teachers unions in this process can extend the decision-making timeline and potentially add complications to realizing change–but working with teachers unions can also mean that the resulting changes are more stable once they are codified into collective bargaining agreements. Figuring out how to innovate alongside teachers unions is critical to not just remaking educator roles, but to making lasting and far-reaching changes to the teaching profession.

The Springfield Empowerment Zone Partnership: Empowering teachers to improve schools

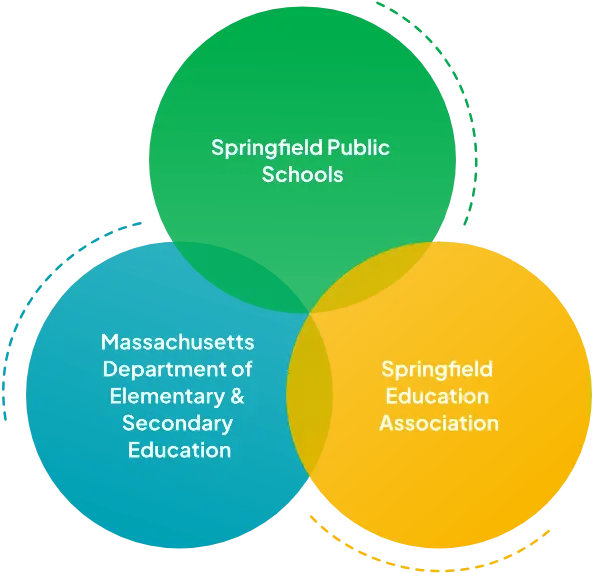

The Springfield Empowerment Zone Partnership (SEZP) is one such system actively working to break the mold. Since 2015, “the Zone”—a partnership between Springfield Public Schools, the Massachusetts Department of Elementary and Secondary Education, and the Springfield Education Association (SEA) teachers union—has empowered teachers to make decisions about their day-to-day work lives as well as school operations. Research suggests that involving teachers in significant decisions can increase satisfaction and reduce burnout—key goals of many innovative staffing strategies.

After multiple unsuccessful attempts to improve the performance of several failing middle schools, Springfield Public Schools turned to a radical solution: decentralizing school improvement decisions by ceding power to the schools themselves. In 2015, the district, state, and the SEA joined together to form the Springfield Empowerment Zone Partnership, an independent nonprofit that initially began with a focus on school and principal empowerment. Over time, the model morphed to include a focus on supporting teachers in making decisions on staffing, spending, and other critical operations. “The people closest to kids need to make the decisions for that school community,” described one SEZP leader.

Each SEZP school has a Teacher Leadership Team (TLT). This group of teachers works with their school leaders to make both short-term decisions based on teachers’ immediate instructional needs and concerns, as well as long-term, continuous improvement plans grounded in students’ state test performance.

While the model is similar to leadership teams in other schools, the SEZP TLTs have real authority that is now codified in their collective bargaining agreement. One leader described how TLTs do more than just tinker: “Schools have complete autonomy over the schedule. They create the hours, they create the staffing, the roles they create. They have complete budgetary autonomy, curriculum autonomy.” Teachers are elected by their peers to work alongside their principals to make decisions, rather than just offering recommendations. As one teacher put it, “Our principal is a facilitator for the meetings … she votes … but it’s not like her vote trumps anybody else’s vote. She’s just one of five in there.”

Teachers, unions, and system leaders all see benefits

TLT teachers, SEZP leaders, and SEA representatives all reported seeing value in empowering teacher agency in school operations:

- One teacher said that it led to better decisions. “I’m not somebody who is [just] sitting in an office … so, when we make policies or priorities through the school planning process, I know what it’s going to be like to do that with a class of 30 students…so I feel like I can bring realism to decision-making processes.” Another teacher described feeling more ownership. “When things go well, I feel very proud of our school. Because I know it’s our whole team working together and knowing that like, okay we made this action plan and so like I feel very proud like when we get our good MCAS results, when we got MAP results that they do well on, I feel that sense of pride and I do feel a lot more as a part of the school.”

- Leaders also reported that increased teacher involvement results in more satisfied teachers. “A lot of teachers that I work with are very happy to have a seat at that table … They feel empowered and when they feel empowered, there’s natural buy-in. They learn something new and they feel they have efficacy … They do [their] jobs better. That’s what keeps people engaged in the work.” Another leader said, “my staff have said multiple times that they know that their voices are heard and they appreciate it, and our TLT works really well.”

- An SEA union leader affirmed the value of increased teacher voice and involvement: “Under the initial contract [before TLT], teachers only had a voice in their working conditions … there was no empowerment there. But in this contract we moved to, it makes it very clear that in [setting] the priorities, goals, and how you are going to do it, the teachers have a voice in that. That’s more important to teachers because they [previously] didn’t have much power.“

It is important to note that while teachers and leaders report the benefits of TLTs and greater teacher involvement in school-level decision making, research has not yet found a causal connection between changes in teacher empowerment and improved student outcomes. A recent study that focused on the impacts of state-initiated turnarounds found that the SEZP had positive impacts, which suggests that the overall model is promising.

Breaking the molds to empower teachers

Eight years into the Zone, the SEZP and SEA union leaders are still working to build and maintain a new mold that empowers teachers. SEZP leaders have found that since they began breaking the old mold around school (and district) decision making, they have also had to continuously articulate what empowerment is or what counts as a “union issue ” or a “TLT issue.” As one TLT member said, “I think some teachers are still confused about what the Zone is, what the TLT is … there is a lot of confusion about what they can have a say in.” Similarly, a union leader highlighted that “empowerment” can be especially confusing to new teachers since it was never covered in their teacher prep programs.

SEZP leaders are currently addressing this issue by creating a new teacher mentor and induction program as well as a TLT toolkit that teachers can refer to if they have questions. The toolkit, developed with union guidance, helps TLTs put systems in place for team decision making, TLT operations, and continuous school improvement—basically, as one leader said, “how do you actually work as a high functioning team: analyzing data and making decisions for your school?” The SEZP hopes this toolkit will help teachers and leaders reach a common understanding of what the TLT is and how it can support high quality instruction. “People need a lot of guidance, support, models, and explaining [of what empowerment is] because it’s counter to how schools have worked for a hundred years,” one leader explained.

While other districts have thought through breaking the status quo of the teacher mold, SZEP leaders have also had to consider the collective bargaining agreement (CBA) in their plans for change. Traditionally, CBAs require uniform treatment for all teachers. However, school-level teacher empowerment means that TLTs will make decisions that result in different working conditions across schools. For example, traditional CBAs include rules around stipends for additional work. But in the SEZP, schools can create their own rules for providing stipends to teachers for additional duties. This differentiation “allows for all kinds of unique and very customized rules within schools to solve the problems that the school is facing, which is pretty unusual,” noted one leader.

Thanks to a strong partnership between their leaders, the SEZP and SEA have managed to build considerable flexibility into the Zone’s current CBA t. In the words of one leader when discussing this relationship:: “They can say anything to us, we can say anything to them and we still walk out peers in this work. So I feel like that’s really strong.” But there may be limits to that flexibility—one union official noted that managing any more than the dozen contracts they already have would be impossible for their staff.

Looking forward

The SEZP provides a clear example of how to break the mold of the teacher role with meaningful teachers union support— provided there is a willingness, and perhaps a desperate need, to find new approaches to longstanding problems. With multiple chronically underperforming schools, Springfield Public Schools and SEA union leaders worked together for over eight years to empower teachers as decision makers. But, there are still big challenges: teacher empowerment requires new training for educators and it’s not clear how long the union can—or will want to—support a system that deliberately encourages schools to create unique and varying policies. The need to spend significant time breaking teacher molds is not unique to working alongside unions, but union buy-in adds additional considerations to the process. As a result, breaking the molds can take longer. Yet, there are signs that enshrining teacher empowerment in union policy has paid off: while the SEA has had three different presidents in eight years, the Teacher Leadership Teams—and the SEZP—have survived.

The rise of unconventional teaching roles: How do educators in these roles feel about them?

Steven Weiner

Senior Research AnalystRobin Lake

Director