This piece was originally published by The 74.

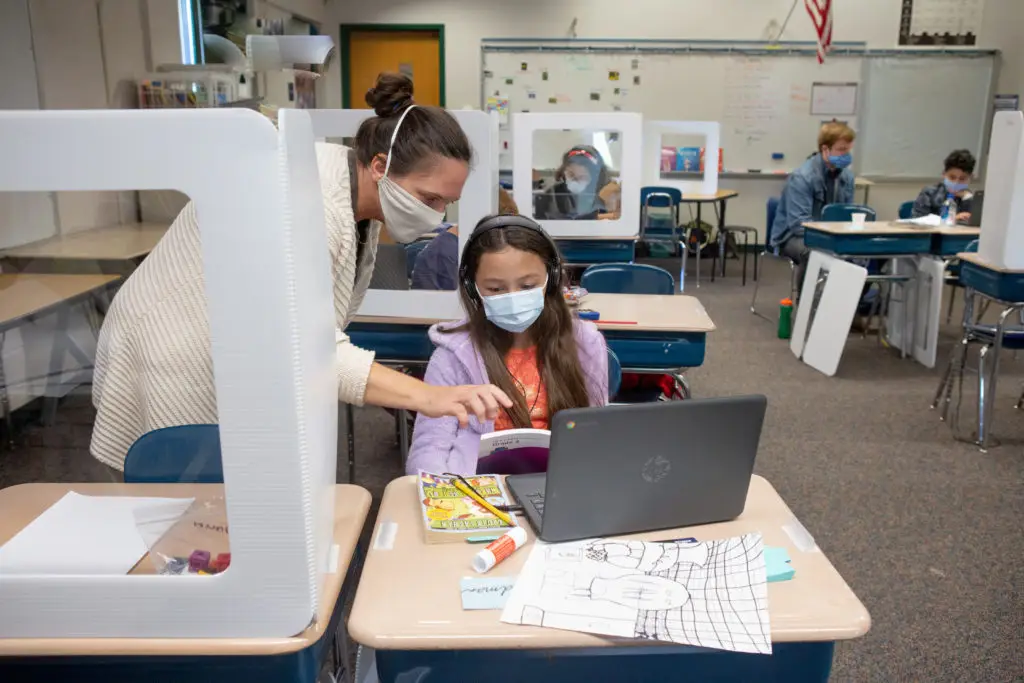

The new National Assessment of Educational Progress results once again underscore the extraordinary impact of the pandemic on U.S. student performance. Average declines in math for fourth and eighth graders were the largest ever recorded, and reading scores regressed to their lowest levels in more than two decades. Since the beginning of the pandemic, achievement gaps between the lowest- and highest-scoring students have widened.

People concerned about student learning should not be surprised by these new national test scores, but we also can’t become inured to them. All recent assessment results showing declines, from NAEP to ACT to statewide exams, make it clear that the typical U.S. student has serious holes in math and literacy knowledge. Districts and schools have the tools to quickly address these gaps through targeted tutoring and other interventions. But little kids have lost critical building blocks, and time is running out for older students.

All this suggests schools should be using evidence-based strategies to help students regain ground. That means assessing and identifying students most in need of help, identifying realistic yet ambitious academic goals, publicly communicating how kids are faring and honestly identifying barriers that stand in the way.

But real-time feedback suggests daily instruction and even public attitudes have swung in a less urgent direction. Our studies of responses to learning loss show many large districts intend to put some federal relief money toward helping teachers accelerate learning — an approach requiring educators to simultaneously offer swift help for those with knowledge gaps. But these attempts have been undermined by staff shortages, student absences and community fights over curriculum, culture and politics.

Our latest report featuring updated interviews with top administrators in five large school systems suggests an awful mismatch between the degree of academic decline and districts’ ability to make the dramatic instructional changes necessary to help kids catch up.

The report is based on a third round of interviews with the administrators, conducted in spring 2022. By that time, district leaders were saying little about the acceleration strategies they had championed earlier. Instead, they told us that the 2021-22 school year was the most difficult they had ever experienced. Amid staff shortages, inconsistent student and teacher attendance, and a lack of reliable data about student performance, they struggled to provide the extra training and support necessary for teachers to successfully carry out the more ambitious instructional strategy needed to close the learning gap.

These district leaders want to pivot to more effective recovery efforts that require long-term changes in teacher practice and student effort, but rigidities baked into the way public education is structured are undermining their efforts.

By law, districts must only set aside 20% of their federal relief money to address learning loss. As a result, America’s largest districts have instead prioritized facilities improvements, social-emotional help for students and new technology, according to our review of their spending plans. Staff training is high on the list, but professional development is highly variable. And getting feedback from districts on its effectiveness is unlikely. When we studied spending and recovery plans from New England districts this summer, we found that fewer than 1% set aside funds to pay for measuring the effectiveness of new approaches to instruction.

Many families, meanwhile, believe everything is fine. Almost half of American parents of school-aged children do not believe the pandemic disrupted their child’s learning, according to a survey in April by NPR and Ipsos. And while most parents thought their child was on grade level at the end of last year, only 44% of their teachers agreed, according to a survey by the nonprofit Learning Heroes and Edge Research.

Districts are partially to blame, because they’re not telling parents how much learning their kids have missed. Among the 100 large districts we’ve tracked through the pandemic, 80 reported they assessed students’ academic or emotional needs last year, our recent analysis showed. But only 18 of those districts publicly shared the results. Families, community members and policymakers cannot help schools and educators in the long road to pandemic recovery if they don’t have an accurate sense of childrens’ current needs.

The sobering new test scores, combined with declines on the ACT and also on statewide achievement exams, suggests districts need more encouragement to double-down on acceleration strategies, such as just-in-time tutoring and extended learning. That’s the only way schools will be able to help more students keep up with grade-level coursework and avoid long-term consequences. Failure to pass eighth-grade algebra, for example, significantly increases the risk of dropping out of high school. And holes in math and literacy will prevent students from getting into, or succeeding in, competitive colleges and high-paying careers.

Teachers clearly need more support. According to surveys included with the new NAEP results, only half of fourth- and eighth-grade teachers reported feeling confident in their ability to address pandemic-induced learning gaps.

Parents must play a stronger role, too. They should ask their child’s teacher for assessment results and information about their child’s mastery of grade-level skills. They should also ask how their school plans to narrow or eliminate those gaps this year and in the years to come.

However, our research shows that the prospects for districts to do these things are growing dim. In this emergency, abandoning strategies that prioritize acceleration over remediation portends trouble. It’s evidence of built-in system rigidity, and it is fatal in this context. By not identifying kids who have lost the most and better addressing their individual needs, districts may risk continued enrollment declines, as families with resources seek alternative schools.

Out-of-the-box solutions — like implementing new approaches to preparing teachers and updating their skills, differentiating teacher roles so some can work in teams and provide just-in-time help to struggling students, making the best courses available to more students and providing learning opportunities from community groups and online providers — are critically needed.

Now that the facts about learning loss are clear, states and districts need to parse the numbers and engage in an honest conversation with families and communities. Governors, business leaders and advocates must partner to design creative solutions. Given the implementation challenges districts are facing, all plausible solutions should be on the table, including flexible funds that parents can spend on academic tutoring or mental health supports; data snapshots and learning plans for every child; and more research partnerships with local universities to better measure the effectiveness of new strategies.

If educators and families carry on as normal and revert to pre-pandemic habits, millions of kids may never recover lost knowledge and skills before aging out of school. That’s morally unacceptable and will ultimately damage the country’s prosperity and stability.