Just two years after ChatGPT’s public introduction, generative AI has rapidly transformed many aspects of society and the workplace. McKinsey’s 2024 State of AI survey of global executives highlights a surge in AI adoption over the past year: 65% of respondents say their organizations regularly use generative AI—nearly double the figure from ten months prior—and 75% predict that it will drive significant or disruptive changes in their industries in the years ahead.

The picture in K-12 is still emerging. Last fall, CRPE conducted a national landscape scan, finding that most districts refrained from providing clear AI guidance. A representative survey of districts CRPE released this spring with RAND found that most districts planned to train teachers in 2023-24, but very few had actually crafted guidance.

To learn more, CRPE launched a new study of systemic approaches to AI in education to identify “early adopter” school districts and charter management organizations adopting system-wide AI strategies or policy guidance. We have released a preliminary database of emerging school system AI strategies, compiled using publicly available news stories and referrals from AI support organizations. We have also developed an initial analysis of the emerging trends. While these districts are not a representative sample or an exhaustive list of school systems engaging in AI strategies, they offer important insights into emerging AI adoption strategies.

Our initial analysis indicates that early adopter districts fall into a typology of practices. While most are focusing on policy and adopting new AI tools, some are undertaking much more comprehensive approaches to preparing teachers and students for AI literacy and skills.

Beyond tools: Emerging AI strategies also address structure and systemic changes

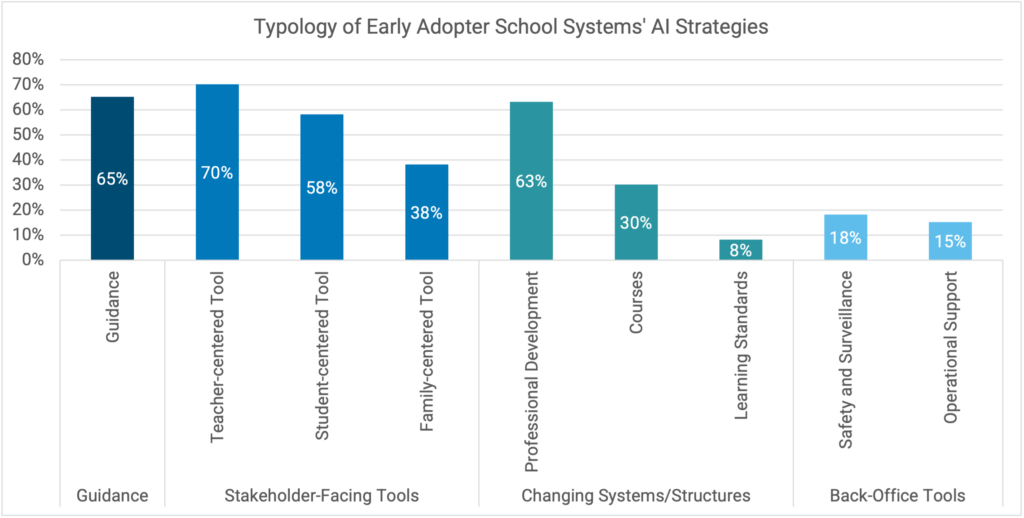

Our review of early adopter practices provides an emerging typology of systems’ AI usage, split across four categories:

- Guidance: Providing guiding language or policy for student, staff, or system use of AI

- Stakeholder-facing tools: Using AI-enabled tools to serve students, staff, and families differently

- Changing systems and structures: Providing professional development to build student, staff, and family AI literacy; offering courses that strengthen student AI content knowledge; and revisiting learning standards to reflect AI-specific student skills

- Back-office tools: Using AI-enabled tools to streamline operations or central office functions or to aid in school safety and surveillance

We identified these categories based on the most common or significant strategies that systems reported. The diversity of approaches reflects AI’s wide-ranging capacity and the range of problems that systems currently trust AI to help solve. These categories are not exhaustive; we will add to the typology as new practices emerge.

Figure 1: Typology of Early Adopter School Systems’ AI Strategies

Based on CRPE’s AI Early Adopter Database of 40 school systems.

Most—but not all—early adopters are providing guidance. Of the 40 school systems we studied, 26 (65%) have provided publicly available guidance to staff, students, and families on using AI. That means an entire third of systems are engaging in AI strategies without offering formal policies or guidance to schools. This is a higher number than CRPE and RAND found in our Fall 2023 survey (using a different, nationally representative sample). Just 5% of districts in that survey provided guidance by adopting AI-specific policies, and another 31% planned to develop policies in 2023-24. Not surprisingly, early adopters think more about policy and may be a good reference point as other districts grapple with AI guardrails.

The guidance itself ranges widely. Some systems have approved minimal revisions to existing student or staff handbooks (such as Boulder Valley School District, which integrated AI references to its student use of technology and student conduct policies this summer). Others, like Issaquah Public Schools, have published new sections detailing appropriate AI behavior in their responsible use policies. Still others have produced entire new frameworks and webpages outlining the system’s stance, recommendations, and expectations around AI use (such as ABC Unified School District’s new Responsible Use of AI page and roadmap).

Most early adopter school systems are exploring just a few aspects of AI. The most common strategies include using AI-enabled tools for key stakeholders (teachers, students, and parents at 70%, 58%, and 38%, respectively) and providing professional development opportunities (63%). A smaller number of systems report creating new courses or new learning standards around AI content knowledge or skills (30% and 8%, respectively) or using tools for safety and surveillance or central office functions efficiencies (18% and 15%, respectively).

While we tracked eight AI-centered strategies, most systems are exploring only half of those strategies or fewer.

Table 1: Systems Organized By Number of Reported AI Strategies

| # Strategies Reported | # Systems |

| Two Strategies | 6 |

| Three or Four Strategies | 28 |

| Five or More Strategies | 6 |

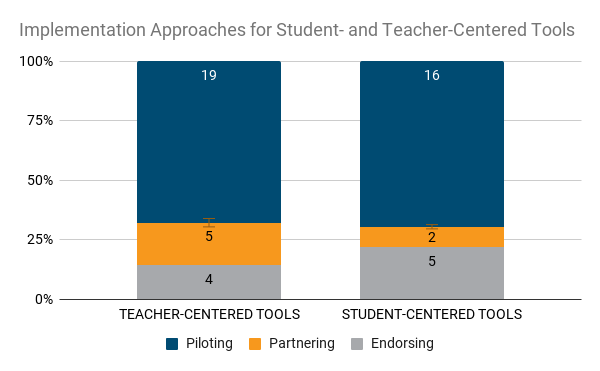

Early adopters take different approaches to scaling AI-enabled tools. These 40 school systems collectively endorse or partner with 65 tools (this excludes open-access large language models like ChatGPT, Claude, or Gemini Plus, or public search engines like Perplexity.ai). The most frequently mentioned tools are MagicSchool, SchoolAI, and Writable.

The 28 systems using AI-enabled teacher tools indicate three different adoption strategies: conducting classroom or campus pilots for a specific tool(s), announcing a partnership with a particular tool (or tools), or publicly endorsing a select set of tools. Twenty-five systems follow a similar distribution for scaling out student-centered tools.

Figure 2: Implementation Approaches for Student- and Teacher-Centered Tools

Based on CRPE’s AI Early Adopter Database of 40 school systems. Student-centered tools n=23; Teacher-centered tools n=28.

A handful of systems are advancing more coherent AI strategies

While most early adopters are exploring a small number of AI strategies, six systems detail far more comprehensive approaches to AI adoption with five or more strategies underway (see Table 1). These systems typically connect their AI efforts to a strategic plan and broader vision of change. They tend to invest in both professional development and AI-enabled tools and couple this with exploring new curricular or back-office approaches.

For example, Colorado’s St. Vrain Valley School District includes “cutting-edge technology and innovation” as one of ten strategic plan pillars. It gives students access to AI-focused hybrid courses and provides them with after-school and summer programming on AI. It asks students to use AI to solve local problems, such as measuring animal populations in the local ecosystem and training elders in AI to reduce fraud abuse. It endorses a range of AI-enabled student and teacher tools, including AIVA, Brisk Teaching, ChatGPT, Diffit, Firefly, Gemini, Khanmigo, SchoolAI, and Writable.

The district provided teacher professional development opportunities in 2023-24, including Exploration AI, a year-long series of professional learning opportunities that used bite-sized, gamified, and personalized approaches. It will continue those opportunities this year. St. Vrain also provides “”AI Pop Up learning events for students and staff to engage in hands-on experimenting and idea sharing, and it uses Edthena’s AI Coach platform to support teachers with self-observation, goal-setting, and lesson planning. The district hosted several AI events for students and educators, including a Day of AI in December 2023 as part of their annual Computer Science Education Week and the World Artificial Intelligence Competition for Youth.

Ednovate Schools, a charter management organization in California, has established three guiding questions to frame its AI work: 1) Does this promote equity? 2) Does this promote personalization? 3) Does this promote sustainability for staff experience, as well as revenue and expenses? Ednovate provides access to Khanmigo, an AI-enabled tool that supports student learning and assists teachers as a universal intervention, and gives all teachers access to Google’s Gemini Plus accounts. Ednovate is also piloting MagicSchool, a teacher lesson planning tool, and TeachFX, which allows teachers to audio record lessons at select campuses. This fall, it provided professional development to staff across the network on these tools. This year, the Ednovate network is also exploring how to better integrate AI into back-office functions. It is identifying bottlenecks and inefficiencies and has created detailed process maps outlining ways AI can streamline operations for departments like HR. It also audits internal student and teacher data sets in anticipation of using AI to analyze, visualize, and find new data-driven solutions. It has documented these initial efforts through work with AI for Equity.

While systemic AI adoption is nascent, early adopters have the opportunity to drive national guidance and practices in 2024-25

Last fall, we encouraged school systems to take a proactive approach to AI by providing training, building partnerships with expert organizations, communicating regularly with parents, and setting initial guidelines. We also urged state departments to set guidance to help districts do this work. A lot has happened since then: 24 states have shared guidance, and a small but emerging group of districts and CMOs is publicly exploring system-level AI adoption.

While the field has progressed since last year, systemic AI adoption is still nascent. The school systems studied here are still setting guidelines, exploring tools, and implementing professional development. This makes sense: systems are likely being careful not to go too far, too fast while still learning the capacity of new generative AI technologies. So far, few systems have publicly signaled AI as a tool that might disrupt historic inequities or publicly explained how they plan to address the digital divide to prevent a further AI divide.

2024-25 provides a critical opportunity for early adopter systems to deepen their work, communicate their learnings, and help educate the broader field on the vast nature of problems that AI can help solve. They have many ways to do this:

- Pilot new ideas and document what does and doesn’t work. Many early adopters are conducting school- or campus-wide pilots of AI-enabled tools and offering professional development for staff to deepen their understanding of AI. Some offer more engaging, hands-on learning opportunities, including creative, play-based learning environments where adults can experiment with tools, learn from mistakes, and shift their mindsets about AI use. The field would benefit from more concrete use cases demonstrating how specific tools address real challenges. Ideally, school systems would document and share their lessons learned, enabling other organizations to build on their early efforts.

- Invest in AI literacy for adults and students at all levels of the organization, from classroom to boardroom. Systems cannot know how to solve problems differently using AI until they understand the range of its capacities and tools. Create opportunities for staff at all system levels to practice AI regularly and deeply. Tap into the wisdom generated by early adopter teachers and provide access to trainers or coaches with advanced AI expertise.

- Center AI on the needs of students, families, and the broader community. Lasting school changes require genuine community buy-in and engagement. Many families lack exposure to AI or a clear understanding of its applications. Early AI adoption trends show a skew toward predominantly white and lower-income systems. To address this, systems must maintain transparency around AI resources and ensure equity of access. Early adopters can democratize data and actively engage families and communities as thought partners in this work.

- Articulate how AI can help solve long-standing, intractable challenges and how the system will guarantee equitable access to AI resources and strategies. As early adopter systems deepen their understanding of AI’s wide-ranging capacities, they can “look around the corner” to understand new ways AI can help schools address deep-set challenges and inequities. For example, how can AI reenvision how families and students navigate learning differences, language differences, or cultural differences to build trust and alignment? Our communities need early adopters to model ways AI can help us allow historically marginalized students to thrive and build a new vision for what’s possible.

We urge states to provide both guidance and coordinated resources to help districts undertake this work.

We will publish ongoing findings about the AI landscape as we collect more data this fall and will continue to update this database of early adopter practices. We are also launching a deeper study of AI early adopter school systems to understand the barriers and enablers driving AI adoption. If you would like to nominate an early adopter district for the study, contact us at crpe@asu.edu.