When people lament that innovation is not possible in “regular” districts—ones that are overseen by elected school boards and working with active teachers unions—we at CRPE often point to Denver Public Schools. We’re not alone in noticing Denver—cities around the country have heard about its energy, new ideas, and solid implementation. Last year alone, more than a dozen city teams visited Denver to try to bring some of its ideas back to their own communities.

But this enthusiasm is not universal. In a recent Denver Post article about the challenges facing Superintendent Tom Boasberg in the upcoming school board race, one interviewee remarked that his “national notoriety is pinned more to the change that DPS has been willing to initiate and less on the results that it has produced.”

Actually, Denver has produced results. During Boasberg’s tenure, graduation rates rose and dropout rates fell. According to a 2012 study by a local foundation, over four years, 68 percent of new charter schools and 61 percent of new innovation schools exceeded the district median in student growth. Independent researchers found that the district’s teacher compensation reform was associated with improved student achievement. And the district’s new enrollment system, which allows families to apply for any of the city’s public schools with a single application, matched 83 percent of students to one of their top three choices and, as hoped, showed that families across the city demand high-performing schools.

Concerns remain, of course—but the city is working to address them. When the foundation report revealed that only 32 percent of the city’s turnaround schools performed above the district average, the district sought to open new schools rather than rely on turnarounds. Researchers found that the high-quality schools that families prefer aren’t evenly distributed across the city; local civic leaders are keeping a close eye on the progress of the district’s landmark effort to improve schools in the historically underserved Far Northeast section of the city.

Dedicated opponents of reform will never be satisfied. But what about the broader community? What evidence do they need in order to decide whether the reforms are working? There are some other ways Denver school officials might show how students are better off now than they were before the reforms began. Here are some examples of what’s possible:

- District staff could model the long-term academic trajectory for students in a school that was slated for closure compared to students in the new schools.

- The district could illuminate how much easier it is for low-income families to access high-performing schools.

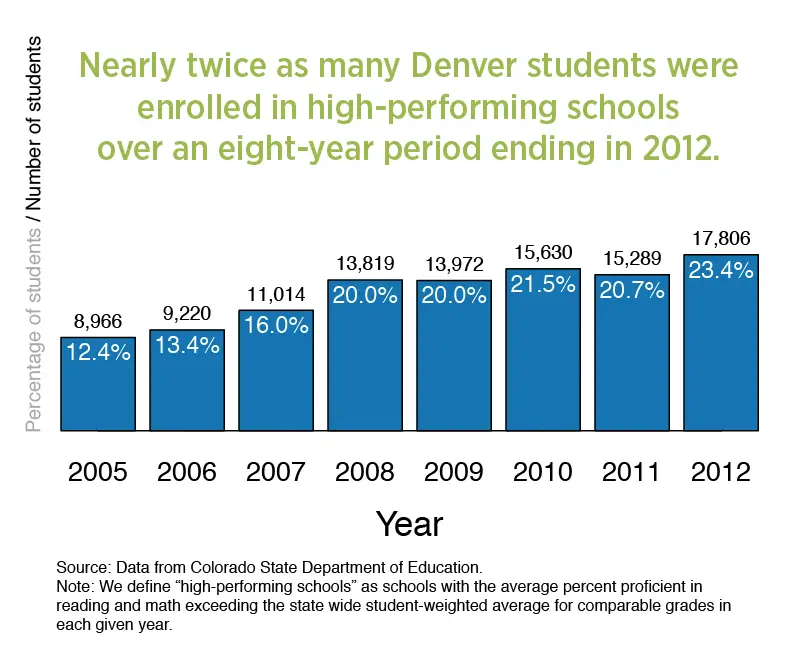

- The district could (as we’ve done in the example here) show that more students than before are attending high-performing schools.

Without this kind of evidence, families and other voters have no way to sort through claims and counterclaims and determine whether the district really is on track to provide every child with strong school options and the potential to succeed. When debates and decisions are not based on facts, people are left to follow the loudest voices, not the best ideas.

To help districts—from those at the nascent stages of reform to those, like Denver, far along in the work—CRPE has started The Evidence Project. The Evidence Project is tracking the work of participating cities, and common initiatives across cities, to see what’s working and what’s not. We start with baseline data and then dig deeper to understand how different aspects of a district’s reforms are impacting students. What happens to student outcomes when new schools are opened? When budget authority is shifted to school principals? When enrollment systems are unified across all city public schools? The goal of this endeavor is not to play “gotcha,” but to give an unvarnished yet constructive assessment of which measures help students and which don’t.

It is fair to argue, as critics have in Denver, that more needs to be done to address persistent achievement gaps, and that gains have been too slow. We all want better for kids in Denver, and everywhere else. We at CRPE are hoping that with clearer evidence of what reforms yield—and what they don’t—communities will be able to make better decisions.