States are the first line of support to help schools translate federal special education guidance into practice. But our first-of-its-kind analysis shows the amount of help they provide varies widely in different parts of the country.

We’ve analyzed special education guidance provided by all 50 states and Washington, D.C., complementing our colleagues’ analysis of district COVID-19 responses and the role of states in driving them.

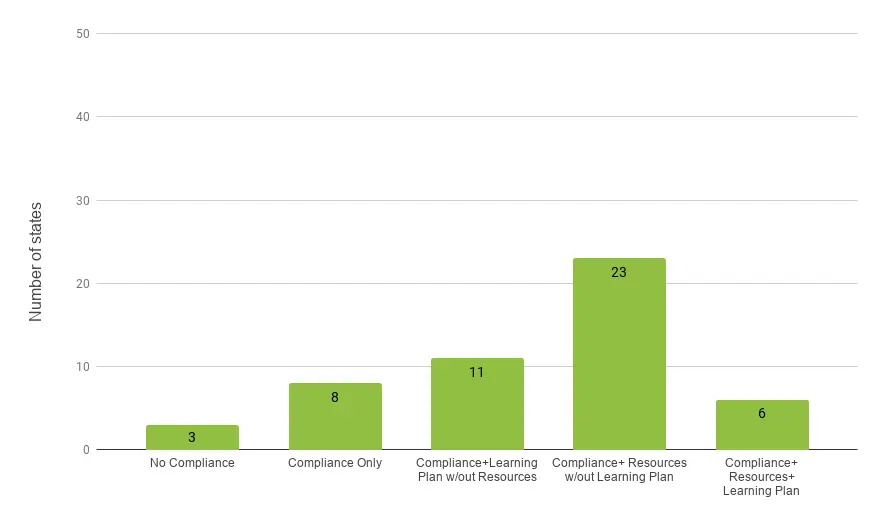

Our analysis places the guidance states give to schools and districts into three main categories: 1) interpretation of legal guidance, 2) requiring special education in distance learning plans, and 3) providing educational resources for special education administrators and teachers. The figure below shows how many states provide which type of guidance.

The Vast Majority of States Provide Guidance on Compliance-Related Topics, But After That, It’s a Mixed Bag

Only six states pull all three types of levers, which will prove increasingly valuable as districts seek to educate students with disabilities without federal waivers of civil rights laws. Texas provides some of the most comprehensive resources, including a table of evaluation components based on what can be done in-person or remotely. Indiana developed a document to help schools design daily programming for students with significant disabilities. And Arkansas has both set the expectation that students with disabilities will be a top consideration in designing remote learning plans and created a host of resources for the implementation of those plans.

On the other end of the spectrum, states such as Hawaii, Nevada, and Utah provide no publicly accessible resources on their websites—not even federal guidance. In some states, special education information existed but was hard to find.

Too many districts and schools are on their own to figure out how to ensure that students with legally mandated Individualized Education Programs (IEP) continue learning while school buildings are closed. State leadership is needed—not only to help schools avoid lawsuits, but to ensure they limit learning losses—and maybe even unlock learning gains—for students who could benefit most from fundamental changes to the learning experience.

All But Three States Offer Regulatory Guidance

Through our analysis, we find that 47 states and D.C. provide clarification on basic building blocks of federal special education law, such as holding IEP meetings, evaluation timelines, and providing services to students.

Some states stop there, leaving the specifics of special education planning to schools and districts. For example, the Arizona Department of Education’s guidance states that it “is not in any position to indicate what is medically safe for a family or for specific students.”

On the other hand, New Mexico provides a detailed frequently asked questions web page that gives very specific responses for what district requirements are.

Some states may be reluctant to give specific guidance to districts, or to do so on public-facing websites, like New Mexico, out of concern that their advice could expose them to lawsuits.

The translation and dissemination of legal guidance is both straightforward for states and urgent for districts. However, detailed guidance that goes beyond restating IDEA requirements on mission-critical questions, such as how to conduct remote evaluations, is essential for schools and districts to educate all learners under extraordinary circumstances.

Without additional practical support from states, schools and districts are on their own to figure out how to meet the regulatory expectations set by the federal government and avoid exposure to lawsuits as they work to ensure they educate all students under extraordinary circumstances.

When It Isn’t Required in Remote Learning Plans, Special Education May Be Overlooked

Our review of state websites finds that 27 states require districts to submit remote learning plans. Of these, 18 expressly require districts to include special education in those plans.

Washington State gives detailed suggestions on how districts can create a remote learning plan, including focusing on the needs of students in special education. However, the state’s Office of the Superintendent of Public Instruction does not require districts to submit those plans. Requiring districts to submit learning plans that include special education creates a stronger incentive for districts to develop the structures needed to uphold the plan. Anything else is merely a suggestion and lacks accountability structures to ensure schools and districts explicitly plan for the needs of a vulnerable population.

States must start developing requirements now for fall plans, whether for brick-and-mortar, remote, or hybrid instruction. These plans must prioritize the needs of students with disabilities to ensure they are not overlooked.

Districts Need Resources from States to Help Implement Special Education in Practice

Beyond legal guidance, 29 states provide additional curricular resources for special education to support districts. These resources are geared toward helping special educators and related service providers, such as speech and occupational therapists, educate and support students with a variety of disabilities remotely.

There is large variation in the resources states provide. North Carolina, for instance, created a Google Site to provide special educators a wide range of resources for preschool to post-secondary transition and for various disabilities. Other states provide support, such as detailed checklists, sample student schedules, and family resources in a ready-to-use format.

Indiana and Arkansas provide resources to help schools and districts provide accommodations and modifications in a remote learning model. For districts without the capacity to reinvent the wheel or sift through hundreds of website links, states can function as an important institution to aggregate and disseminate these resources for special education.

Phase 2 of Special Education Must Include Supports for Practice

States should not wait passively for additional guidance from the U.S. Department of Education on how to educate and serve students in special education. There will likely be no waivers of special education laws, so evaluations, special education services, and IEPs must move forward.

States can try to ease the burden of these requirements for districts and schools by providing practical resources. They should:

- Help schools and districts acquire subscriptions to online assessment tools.

- Provide relevant training and support documents for IEP evaluations, records reviews, and other critical special education functions that have been disrupted by the crisis.

- Emulate practices, such as Colorado’s weekly office hours, that help special educators troubleshoot needs that arise in specific areas, from supporting students with autism spectrum disorders to accommodating visual impairments.

- Coordinate regional special education units (such as California’s Special Education Local Planning Areas or Washington State’s Boards of Cooperative Educational Services) so each can focus on a specific statewide need (for example, how schools can support students’ transitions after high school graduation) and build out a set of resources to meet that need for the state.

- Showcase districts and schools that maintain remote co-teaching, small-group instruction, and other inclusive supports for students with disabilities in their remote learning plans, so others can learn from them.

Many states currently share Arkansas’ document on supports for students with significant cognitive disabilities. Federal special education law does not vary by state so there is no reason not to share tools that will help make implementing the law easier. Much like how states are collaborating to allocate ventilators or decide when to allow certain businesses to reopen, they should work together across state lines so educators have the most possible tools available.

The federal guidance is clear: the timelines and activities mandated in special education laws aren’t going anywhere. The role of states must move beyond translating federal guidance and toward ensuring schools can educate their most vulnerable students to the greatest extent possible.