The Governor’s Emergency Education Relief Fund (GEER I and II) gave states $4.25 billion in discretionary federal dollars to support K–12 schools, higher education, and workforce initiatives. These were welcome resources, coming just as the pandemic accelerated unemployment and exacerbated declining college enrollment, hitting those from low-income backgrounds hardest.

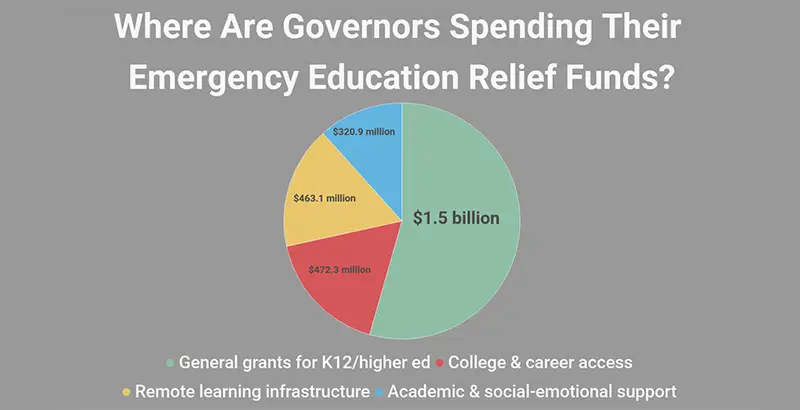

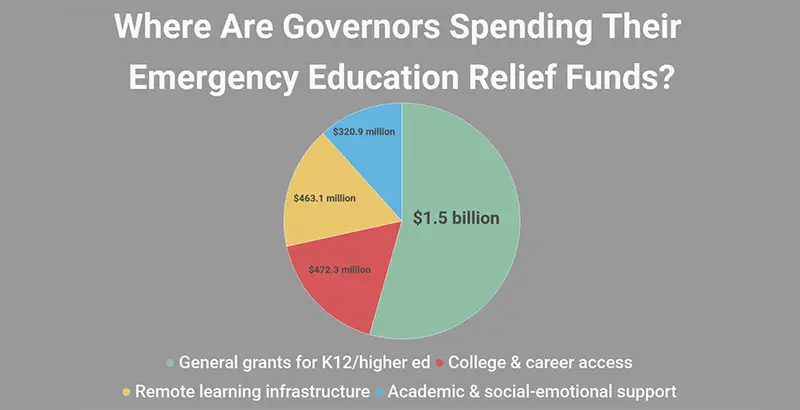

As of May 1, about $1.5 billion remained from GEER I and II; only eight states had used even a portion of their GEER II funds. And governors still have time to use new American Rescue Plan (ARP) dollars to invest in initiatives that prepare youth for the workforce, like Connecticut is doing through summer internships and college and career navigation tools. If governors act boldly and creatively, remaining GEER and ARP funds can lay the groundwork for closing opportunity gaps through education and workforce initiatives.

Most states are not yet putting youth hit hardest by the pandemic on a path to success. Instead, they are investing in one-time college scholarships or short-term supports that will end once funds run out—such as a traveling bus with academic resources.

Policymakers can look to their peers in the 11 states that have used GEER to fund programs focused on long-term, systemic improvements to college and career access. These forward-thinking states awarded grants to colleges for initiatives that enroll and retain underrepresented youth, increased access to college and career learning through online platforms, awarded competitive grants to drive systemic change, and promoted learning and collaboration across education entities.

College and Career Access—The Second-Largest Spending Category of the Governor’s Emergency Education Relief Fund

So far, states have spent $472.3 million in GEER funding on college and career readiness — more than on remote learning and academic and social-emotional support.

Of the $2.75 billion spent on GEER I and II, college and career access is the second-largest spending category behind general operating grants:

Note: This analysis is based on the 50 states that have spent some or all of their GEER I funds, and eight states that had spent at least some of their GEER II funds as of May 1, 2021: Iowa, Kentucky, Maryland, Michigan, Minnesota, Mississippi, New Jersey, and Pennsylvania. A single state may have invested in multiple types of initiatives.

While college and career access is a common investment, the majority of states have used GEER funding to meet immediate needs, like setting up remote learning or offering pass-through grants to K–12 and higher education. This spending makes sense as an emergency response, but half of the states that have dedicated GEER II funds are still distributing grants directly to districts and institutions of higher education — with limited direction or oversight.

Of the states that focused GEER appropriations on short-term, limited programs, seven used GEER funds for scholarships to help youth access college, like Texas, which spent $103.5 million on one-time scholarship grants. Arizona used funds from GEER I to launch the Graduation Alliance this spring, which provides counseling and academic coaching to disengaged youth, but only for six months.

How 11 States Are Prioritizing Funds to Outlast the Crisis

We did identify 11 states that invested in initiatives that are designed to outlast the pandemic and have the potential to address long-standing gaps in college and career access:

1. Helping postsecondary institutions enroll and retain underrepresented youth in college

Some states are doing more than investing in scholarships by helping higher education make systemic changes:

- Illinois put $3 million toward targeted initiatives that enroll and retain underrepresented and first-generation students.

- New Jersey Governor Phil Murphy is using a competitive grant program to incentivize institutions of higher education to overhaul access and retention strategies so they better support working adults, students from low-income households, and underrepresented students of color. The proposed programs must align with best practices identified by the governor.

2. Building online platforms that expand access to college and career counseling

States like Virginia used GEER funds to expand online course platforms. But the states listed below went one step further by increasing access to advanced courses that will help prepare youth for college and careers:

- Oklahoma added AP and advanced coursework as a resource for youth in schools who don’t have these opportunities. Louisiana created a statewide dual-enrollment portal so more high school students can earn college credit.

- South Dakota launched UpSkill to help dislocated workers reskill rapidly. GEER paid for participating higher education institutions in South Dakota to create eight online certificate programs in high-demand fields. These microcredentials can be earned with as few as 18 credits—at little or no cost to the student—and can be used as the foundation for an associate’s or bachelor’s degree later.

- Florida and Idaho increased access to career and technical education and work-based learning by investing in online simulations and equipment that students can use for years to come.

3. Launching competitive grants to drive systemic change:

Instead of operating grants, states allocated grants to make impactful innovations:

- Arizona invested $1.5 million from GEER I toward community- and school-based initiatives that offer personalized learning, sometimes called pods or microschools.

- Colorado Governor Jared Polis awarded $40 million to school districts, higher education institutions, and nonprofits that proposed innovative ways to serve historically marginalized youth. Out of 32 grantees, 14 focused on college and career readiness. Colorado Mountain College is building an online platform to offer concurrent enrollment classes to 14 districts and 54 rural schools. Metro State University in Denver is creating a pathway program that starts in 9th grade and guides students through college and into a career.

4. Promoting collaboration and learning across education entities:

Partnerships and collaboration facilitate learning and new ways of working:

- In Hawaii, GEER funds were used to create the Governor’s Innovation Team, which regularly convenes leaders from GEER-related grants to share best practices. One GEER-supported network will design parent education and family support initiatives for schools and communities.

- Montana awarded grants to two-year colleges that proposed ways to increase access to training in high-demand careers. The grant prioritized multi-campus collaboration, so over half of the approved programs were collaborations with at least two institutions. For example, three Montana colleges launched a pilot to share a respiratory therapy program, and four colleges are working together to launch a remote IT program.

Most Governors Have Failed to Invest in Sustainable Systems

Only eight governors have used even a portion of their GEER II funds, and ARP allows for a great deal of flexibility over state dollars. States should use at least a portion of their remaining funds to expand access to sustainable, long-term initiatives that promote high-quality, high-value college and career pathways.

As legislators, advocacy organizations, and governor’s offices consider how to dedicate their remaining federal funds, college and career access will likely top the list. States can learn from forward-thinking peers that have used their discretionary funds to put youth most impacted by the pandemic on a path toward opportunity while closing historic gaps in access so youth can continue benefiting from these investments long after the pandemic is over.

States have a historic opportunity to invest in initiatives that will lead to systemic change and address long-standing inequities. As we adjust to a post-COVID education system, this is what should be the top priority—not well-meaning but short-term programs. States must think beyond immediate recovery and reimagine systems to put students on a path towards successful college and career readiness.

The post originally appeared in The 74.