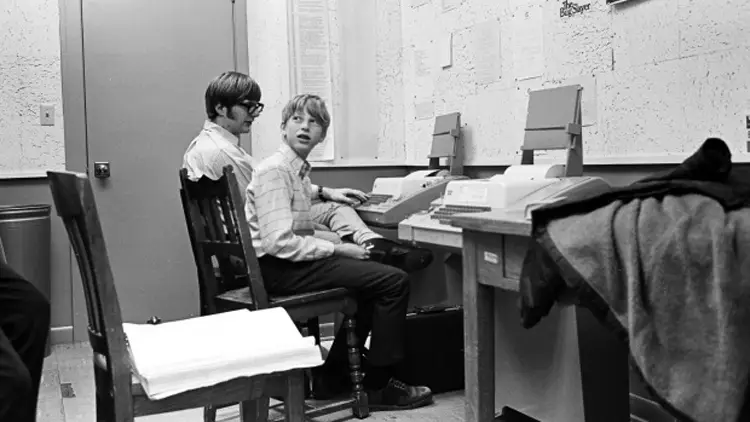

Seattleites are familiar with this 48-year-old picture of two teenagers in the basement of Lakeside, a local private school. It shows Bill Gates and Paul Allen—who would later found Microsoft—working at computer terminals linked to the local Boeing Company’s giant mainframe.

This is personalization at work: a school with the institutional and financial flexibility to accommodate students’ differences can nurture talent and link students to valuable learning opportunities, no matter where they are. Highly effective teaching and rigorous classes focus on developing students’ originality and breadth of thinking, not just course-specific learning.

Looking at student work and progress in outstanding independent schools, it’s obvious that personalization is not out there in the future, it is here and has been for some time.

Photo from Bruce Burgess Photo Archive

Yes, this example comes from an independent school whose annual tuition is about double the local public school’s average spending per student. This example of personalization and myriad others in similar schools across the country are possible in part because of well-prepared students and committed teachers and leaders who, like the Lakeside School faculty in 1970, are hoping for great things.

The extra money in such schools buys small class sizes, rewarding though not particularly well-paid faculty careers, and flexibility. On the latter, personalized schools for the elite don’t spend all their money on a fixed set of courses, but guard their flexibility to let students dig deep into a problem or arrange experiences of great value to individual students. These schools will surely make greater use of online learning experiences as they become available.

Which leads to the question: Will public schools have the funding, flexibility, faculty engagement, and aspirations for students necessary to personalize and fully exploit learning opportunities? Even if public schools never get quite as much money as Lakeside School, will they get the freedom to compete effectively in the market for teachers with rare skills? Will policymakers and voters stop trying to control how schools use time and how they teach? Can the schools exploit the learning opportunities available in local businesses, museums, political institutions, and colleges? Will they aggressively utilize online learning opportunities as they emerge?

Or will public districts, schools, and unions fight to protect established school budgets, staffing tables, work rules for faculty, and negotiated curriculum mandates, none of which allow the flexibility and improvisation necessary for personalization? Given the public school system’s current resistance to diversification of schooling opportunities via charter schools, and its pushback against more flexible and transparent uses of funds, the prospects are questionable.

Clearly, the elite already benefit from personalization, and will do so more in the future. Will public school students’ opportunities also grow, so the gaps in skills and incomes don’t continue to widen and might even narrow?

It all depends on how policymakers and public education leaders define their jobs: whether to defend the existing arrangements, or to enable schools and teachers to maximize the opportunities for personalization present in every community.

Starting next month, CRPE will publish a series of research reports and commentaries on the system-level changes necessary to ensure students in public schools get the benefits of personalization.