This week marks nine years since Hurricane Katrina forced evacuation of New Orleans. The rebuilding of public education there has been a real accomplishment. But the schools there have a long way to go.

Due to Katrina, 80 percent of the city was flooded and the floodwaters lingered for weeks. The vast majority of families were forced to flee. Later, children returned to New Orleans schools gradually, some after enduring serious trauma and being out of school for months or years.

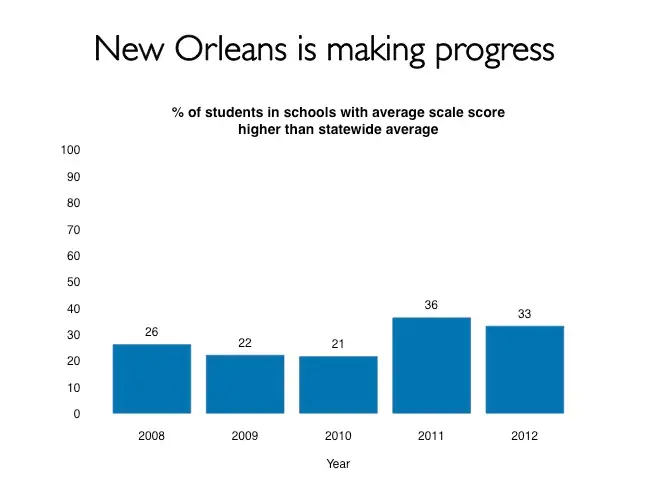

Despite those challenges, schools in the city, mostly overseen by the state Recovery School District (RSD), are not only performing better than before the storm, they are steadily improving. Student test scores, attendance, persistence in school, and graduation rates continue to improve. See the latest on student achievement in New Orleans from Tulane’s Cowen Institute.

But there is a dark side. The majority of children still aren’t on track for college or rewarding careers.

New Orleans children started very far behind. But the kinds of drill-based instruction that could help children overcome the trauma of evacuation and the effects of time out of school are not what’s needed to bring them to college-ready standards.

Can the existing schools, now all charters, adapt to this broader mission, or will it require a new infusion of talent and new school operators? It’s likely that some of the existing schools will evolve and others won’t.

New Orleans and the RSD (or whatever successor institution emerges to oversee the city’s schools) can’t afford to leave well enough alone. The city needs to make full use of the flexibility that chartering gives it, and to continually look for models and providers that meet the current needs of students while also encouraging incumbent schools to improve.

We’ll see whether this happens. Continuous improvement processes challenge human nature in many ways—existing school leaders can resent being judged “not good enough” after making a vital contribution to the city’s recovery. They might organize to keep newcomers out, and citizens might cringe at the thought of being disloyal to schools that have done a lot for children. Public officials might also think they have taken quite enough heat already, and resort to happy talk about the existing schools.

But, if these things happen, New Orleans schools will not keep getting better. The city will lose its advantage as the world’s strongest magnet for people with new ideas and burning desire to make a difference. The education scene in New Orleans will become more peaceful, and the pressure will be off.

Much depends on whether elected officials in the state and city fully recognize what they have. Yes, they have a set of better schools, and have replaced a corrupt and inefficient system. But if the continuous improvement is allowed to stop now, the city will squander its real advantage, which is the ability to change its mix of schools when needs change and promising new approaches appear.