Despite national attention on bolstering summer school options for students who lost learning time during the pandemic, most large districts have not expanded or improved their 2022 summer programming, according to a review by the Center on Reinventing Public Education.

Even after an additional year to plan and more federal recovery dollars available, districts’ 2022 summer programs are mostly the same as last year, or have decreased in type and scope, based on our review of summer learning plans for 100 of the nation’s large and urban districts.

Among the 50 districts that publicly post budget documents detailing their American Rescue Plan spending, just 28 are directing federal relief money toward summer school this year, as of our review May 10.

Among the 100 districts, about 70 are offering summer programs focused on credit recovery and social and emotional well-being. These counts are down from 2021, when 79 districts offered social and emotional support programs in summer, and 74 offered credit recovery programs —

which can help students catch up and position them to accelerate their learning in the years to come. Arlington Independent School District in Texas is offering its Summer Academy for high school students who need to recover credits in a blended learning environment. Some districts, like Charlotte-Mecklenburg Schools in North Carolina and San Francisco Unified School District in California, are allowing students to take credit recovery courses either in person or virtually.

Compared with last year, 70 districts mention specific social and emotional support programs in their descriptions of summer offerings. That’s a surprising decline from 79 in 2021.

The number of districts providing summer bridge programs has also declined, according to the publicly available plans we reviewed. Ten fewer districts (35) than last year (45) will offer bridge programs to help students manage key emotional and academic transitions, such as elementary to middle school or middle to high school.

The findings are important because chronic absenteeism and declining enrollment have plagued U.S. schools. More than 1 million students have left public schools since the beginning of the pandemic, according to the latest Return to Learn Tracker data from the American Enterprise Institute. The summer offers additional time to re-engage students and families and to connect them to academic recovery programs.

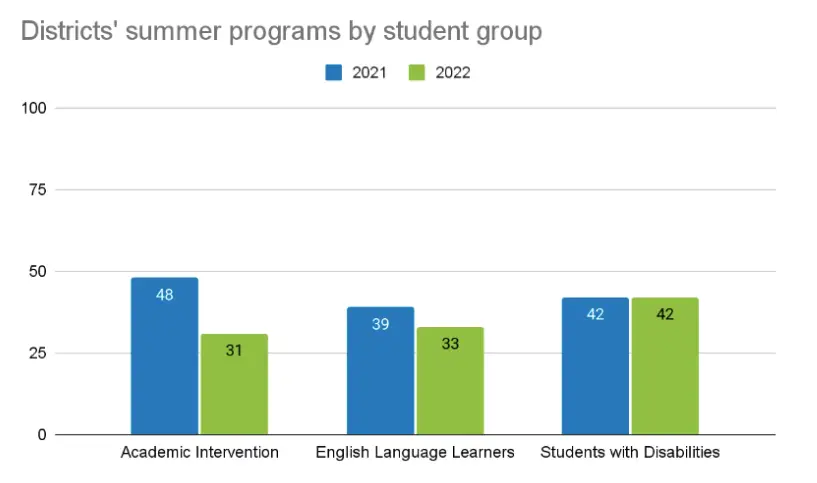

Fewer districts are providing academic interventions and English learner supports

Of the 100 districts in our database, only 31 say their summer programming will focus on academic interventions, a decline from 48 in 2021. Yet the latest data on unfinished learning indicates high-poverty districts that went remote in 2020-21 will need to spend nearly all their federal relief funds to recoup lost instructional time.

The lack of consistent assessment data among English learners makes it difficult to tell how schools can support their learning and engagement needs over the summer. While some multilingual families experienced gains in their original language due to more time at home during school closures, many districts and community groups stated it was difficult for these families to stay connected to schools virtually and to navigate remote learning. Yet only 33 of 100 districts explicitly state their summer programs will focus on students who are learning English, a decline from 39 in 2021.

About 40% of districts we are tracking said they are providing summer school programming for students with disabilities. That figure has remained constant from last year to this year — and it is disappointing that we still don’t know how the other 60% of our 100 districts are providing students who have disabilities with the recovery services they need.

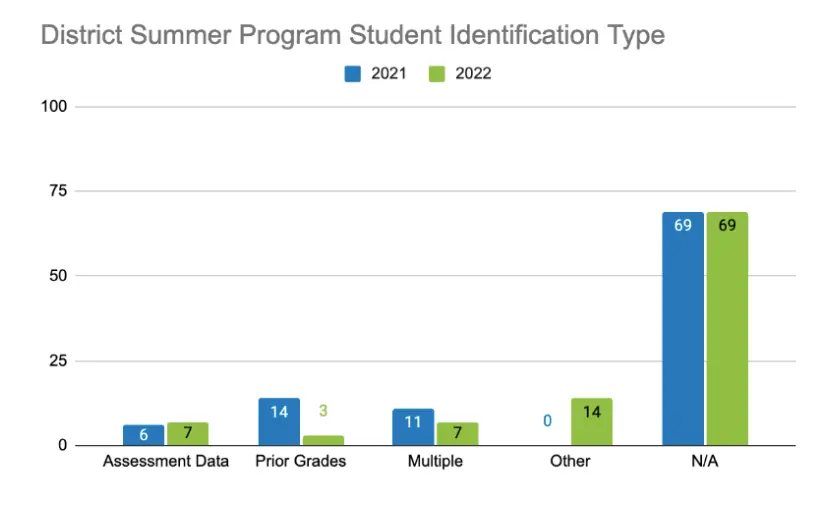

Most districts are not using the right data to identify students for additional summer services

Nearly seven in 10 districts have shared no information about how they are identifying students for summer programs this year — the same number as 2021.

With assessments largely skipped in 2020 and 2021, districts had scant data with which to identify students who needed additional support in the summer. In their absence, some resorted to statistics like grades or attendance. But, with many more tests restarted this year, districts should be able to use these objective measures to flag students in need of more help. Researchers caution against using grades and attendance alone to identify students for summer school, because grades can be subjective and attendance may reflect barriers outside the control of the student, such as a lack of access to reliable transportation.

That’s why it is promising that only three districts reported using grades alone to identify students for summer learning enrollment this year — a decrease from 14 in 2021.

Of the 100 districts, seven are using only standardized assessment data, like interim exams administered during fall, winter and spring, and seven are using a combination of measures to identify students eligible for summer programming.

In Louisiana, Jefferson Parish Schools are reviewing high school students’ reading and math test scores to determine whether to refer them for summer classes. Students can enroll in a summer program and retake their end-of-school-year test.

Some districts are designing summer programs that specifically aim to bolster the skills of students who have fallen the furthest behind. In Texas, Northside Independent School District is reaching out to middle schoolers who failed two to four core academic courses. Another summer program is aimed at high school students who are at risk of dropping out (based on state criteria) or who have not yet passed at least one end-of-course exam.

Districts should move summer programs from the peripheral to core instructional planning and student re-engagement efforts

The pandemic reinforced the need to treat summer programming as more than an afterthought. Yet despite the urgency to address student learning and well-being year-round and to make up for lost instructional time, most large districts have scarcely improved their summer offerings this year.

Districts are heading into the third summer of the pandemic while sitting on a historic amount of federal relief funding. School system leaders and school boards need to include input from community partners, use only accurate data and keep in mind the need to equitably distribute stimulus funding in their plans to address students’ needs — otherwise, summer programming will continue to be an add-on for only a select few students.