Samantha* had been a veteran educator for fourteen years, first as a classroom teacher and then a principal, when the pandemic shut down schools. Last year, when she learned about the then-growing learning pod movement, she thought starting one would help solve several immediate problems.

“[My daughter] needs social interaction,” she said in an interview. “I know there’s other kids out there that need social interaction. I know there’s working parents out there that could use the support of somebody like me, and then it just snowballed from there.”

Running a learning pod turned out to be a transformative experience for Samantha. “This is probably the most professionally satisfied I’ve ever been in my entire career,” she said. And she felt there was no turning back: “[After] this experience, I’m not going back to formal K–12 education. I can’t. You can’t. I want to be able to replicate what I had here. You can’t do that in public school.”

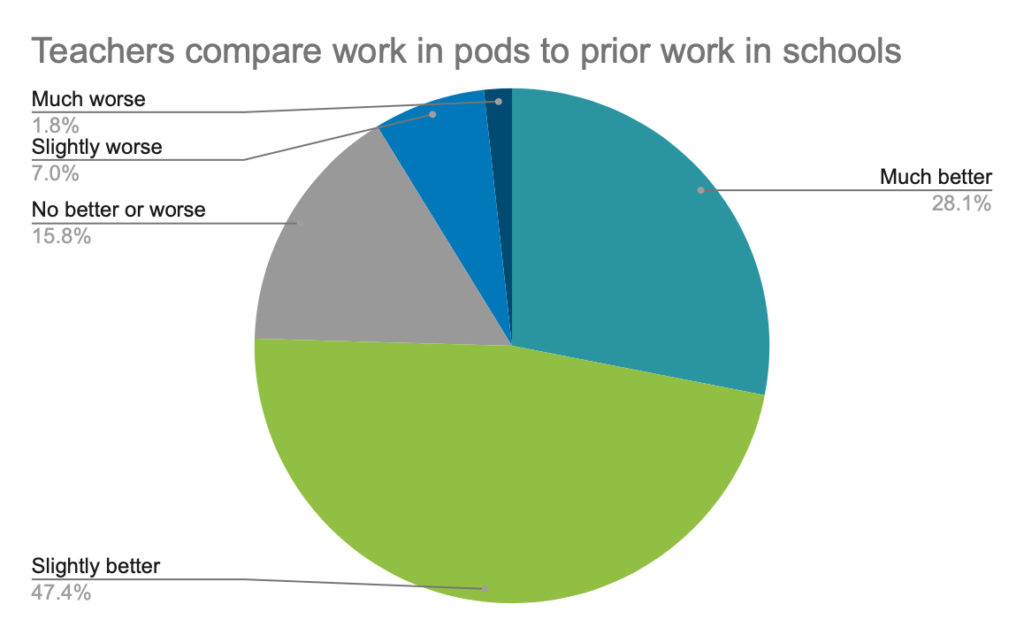

Samantha was not alone in her sentiment. This spring, when CRPE researchers surveyed and interviewed teachers who worked in learning pods, we were struck by how many preferred these learning environments over their prior schools.

The learning pods that proliferated during the 2020–21 school year were unplanned educational experiments that often looked far different than a standard school. They took place in living rooms, community centers, and even neighborhood parks. Many were started by parents who either hired professional educators or took on the role of teacher themselves, often as a complement to their regular school’s remote instruction.

Learning pods were generally small, with most averaging about six students, though they could still be logistically complicated to run. Along with her daughter, Samantha hosted four other elementary schoolers ranging from first to fourth grade and juggled their remote schedules, which shifted throughout the year between synchronous, asynchronous, and hybrid in-person varieties. “We’ve literally been on nine different schedules since we started,” she said during our interview last March.

Note: Data reflect survey results for 57 pod instructors with prior teaching experience.

Despite their complexity and untested nature, instructors found a lot to like about learning pods. According to a majority of the thirty-five pod instructors we interviewed, teaching in pods was emotionally fulfilling and intellectually satisfying. Like Samantha, many explicitly said that they were not interested in returning to a traditional school setting or—if they did not have previous teaching experience—pursuing a career in formal education.

What made their experiences in learning pods so positive and their take on traditional education so pessimistic? The answers could point the way toward a more humane and sustainable teaching profession.

Teaching in pods: The joy of autonomy, creativity, and connection

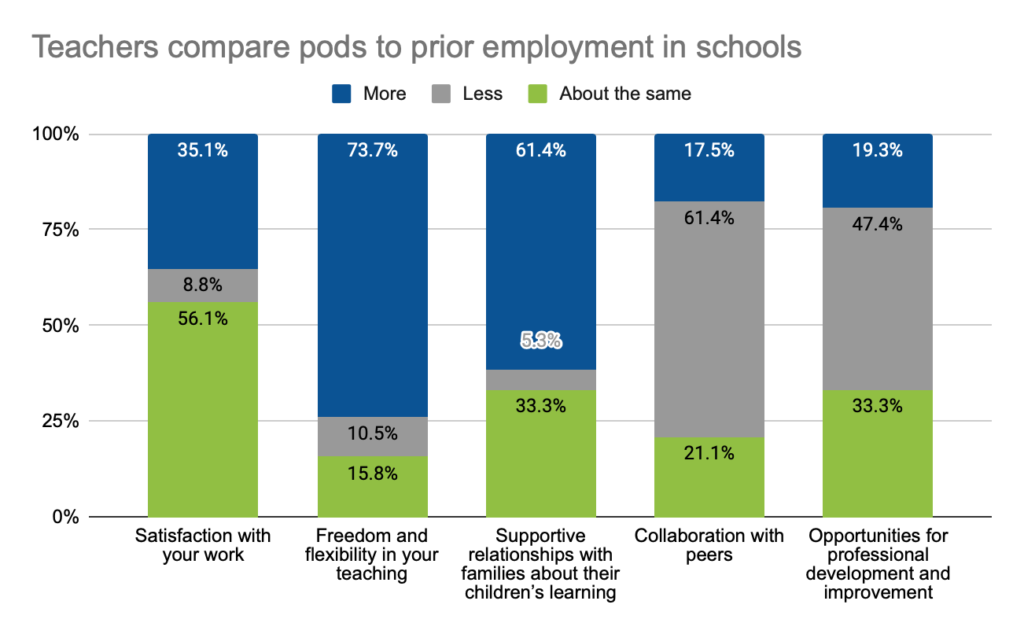

The reasons educators we interviewed enjoyed their pod experience centered on two main factors: the development of close relationships and the professional autonomy to shape what, when, and how their students learned.

Pod instructors frequently cited their ability to get to know their students well. One pod instructor gushed about the experience: “Being able to closely watch them grow and give them so much feedback and all my attention and so much love and just be a close mentor for them. . . . I don’t think I would have expected to feel as just completely fulfilled from this year as I have.”

Many instructors also said that having control over their time, curriculum, and lesson design significantly contributed to their satisfaction with the work. One teacher put it succinctly, saying “the freedom to be creative in how I present the material, even what material to present, that’s been the most fun for me,” while another observed that “much like the kids I’m enjoying the freedom of taking things in different directions. It’s so nice as a teacher to . . . just have the gift of time.”

Note: Data reflect survey results for 57 pod instructors with prior teaching experience.

Interestingly, a few instructors made an explicit connection between this autonomy and the strong relationships they had built with the parents who hired them. “I wish this could be in my actual long-term job . . . I just have loved it,” one instructor said. “I’ve loved the families. I’ve loved getting to know the kids. I’ve loved the freedom and flexibility and the respect that the parents have for me.”

Underlying both the relationship development and instructional flexibility was one of the essential characteristics of all pods: their small size. Yet, size was only one factor which allowed for instructors to be more responsive to students’ needs. As Samantha put it: “I can tell you every single one of their strengths. I can tell you their weaknesses. I can tell you what’s going to set them off. I can tell you what’s going to make them happy. I’ve never been able to do that before in my life, except with my own child, and that’s super powerful.”

Teaching in school: constrained, overburdened, and underpaid

Whether pod instructors had firsthand experience as teachers or were outsiders to the profession, their sentiments about formal education were generally poor. In fact, much of their reflection on the positive aspects of learning pods were expressed in contrast to school.

When parents praised Samantha—the pod instructor mentioned earlier—for giving daily feedback on each of their students, she thought it indicated a major inadequacy of the traditional school experience: “I don’t think that that’s the treatment that they are used to getting from an educator. These are highly invested parents . . . and they still don’t feel like they’re a part of their kids’ education.”

The impression these instructors had of teaching in schools was one focused on constraint, control, and monitoring—and specifically in ways that were not central to student learning.

One pod instructor who planned to return to the classroom lamented that even elementary school teachers will have to forgo many of the creative, exploratory activities they were able to do in pods because of perceived accountability pressures, like the rush to make sure every student was meeting state standards: “You literally can be an effective teacher making a real positive difference in a child’s life but ultimately there are guidelines, there are certain expectations, there’s certain things each teacher has to meet and produce.”

Along with several other pod instructors, she noted that returning to school would mean “going from making pretty good money in the pod to making terrible money.” That said, money was not always a driving factor. One instructor said, “I would much prefer to do this and work directly with the families and forge the relationships that I have with students now in the future as well, knowing that long-term I may not make as much money. This is the ideal job for me.”

Interestingly, one of the few instructors we interviewed who had a negative experience in a learning pod described it as similar to being a classroom teacher: “When I became the pod teacher, I basically became that system that has failed them. I became this . . . really unappreciated person working a thankless job with hours and hours of work being added on without even anyone batting an eyelid about it.” This comment underscores a particularly bleak view on the way public school teachers are viewed and treated.

What could a better teaching profession look like?

While we spoke to a less-than-representative sample of teachers, the combination of positive experiences and an almost uniform resignation that their pod was unlikely to continue beyond the pandemic raises an intriguing question: Why not? What would it look like to normalize learning environments like the pandemic learning communities we studied, provide them with public funding, and make them accessible to all families who wanted to participate—and not just the affluent families with household budgets lavish enough to accomodate teachers for hire?

States should explore policies that allow teachers to operate with a similar level of independence as they had in pods after the pandemic passes. Charter teaching policies could allow teachers to operate one-room schoolhouses or microschools. Education savings accounts could allow families of all incomes to pay for educational services a la carte, giving a top high school English teacher the option of operating in private practice in the same way a medical specialist could.

But creating alternatives to the existing system won’t be enough. Policymakers and school system leaders should not accept the normalization of teaching as an exhausting, micromanaged, and thankless job designed to lead to professional burnout.

Working in learning pods gave the teachers we interviewed a break from that norm. It showed them they could thrive professionally with greater autonomy. It showed them that they could work flexibly from living rooms or home offices, with more flexible hours—as professionals across the country, including the author of this blog post—discovered during the pandemic.

It’s no surprise, then, that these teachers reported greater satisfaction. How much better could we do if we designed educational institutions to treat teachers with dignity, encourage their autonomy, honor their expertise, and reward their successes?

There are pockets in public education where this happens. In certain schools and classrooms, teachers build the lessons they’ve always wanted to build, form authentic relationships with students, and design learning experiences around their students’ needs. But tellingly, these pockets often form outside the “core” of the traditional system—in specific schools with peculiar missions, or on the periphery of schools, in electives or extracurriculars, where teachers enjoy more freedom and students often enjoy more authentic learning experiences. Policymakers and school system leaders should look for these pockets in the school systems they govern, and they should ask what it would take to make the whole system more like that.

Samantha, the pod instructor we interviewed, exhorted school decision-makers to take note of the positive experiences taking place in pods: “I truly hope it does change education, because this is what we need to get back to—not kids being treated like numbers and just pushed through the system.”

The same can be said for teachers.

*Note: We used pseudonyms to protect the identities of teachers we interviewed for this project.