The summer of 2020 has been one of pain and reckoning for the United States. With widespread protests and discussions happening in the wake of George Floyd’s death, there is reason for concern about children returning to school this fall, beyond the physical health factors. Students will likely carry anxiety, anger, fear, and other unresolved emotions that could be barriers to learning or could lead to social tensions or bullying, even online.

Specifically, parents of color are worried that their children may become targets of racism. A national parent survey by the American Enterprise Institute (AEI) finds that 42 percent of all parents are worried that their children will be impacted by racist comments or actions from other students; it rises to 63 percent for parents of color. Furthermore, more than one in two of these parents are worried about their children facing discriminatory police actions both at school and in the community. Fifty-five percent of parents of color fear that their children won’t know who to reach out to at school when they experience discrimination.

Unfortunately, parents’ frustrations surrounding racial discrimination have failed to translate to district reopening policies. Of the 124 school districts and charter management organizations in our fall reopening database, only 22, or 18 percent, include any mention of the current racial climate. Of these 22 districts, 11 specifically mention addressing racial equity in the upcoming school year.

This failure to address racism at school directly contradicts the desires of parents from across the country and demonstrates that while districts were careful to survey families on school reopening plan preferences, they fell short on other critical and timely measures of students’ psychological safety and emotional well-being.

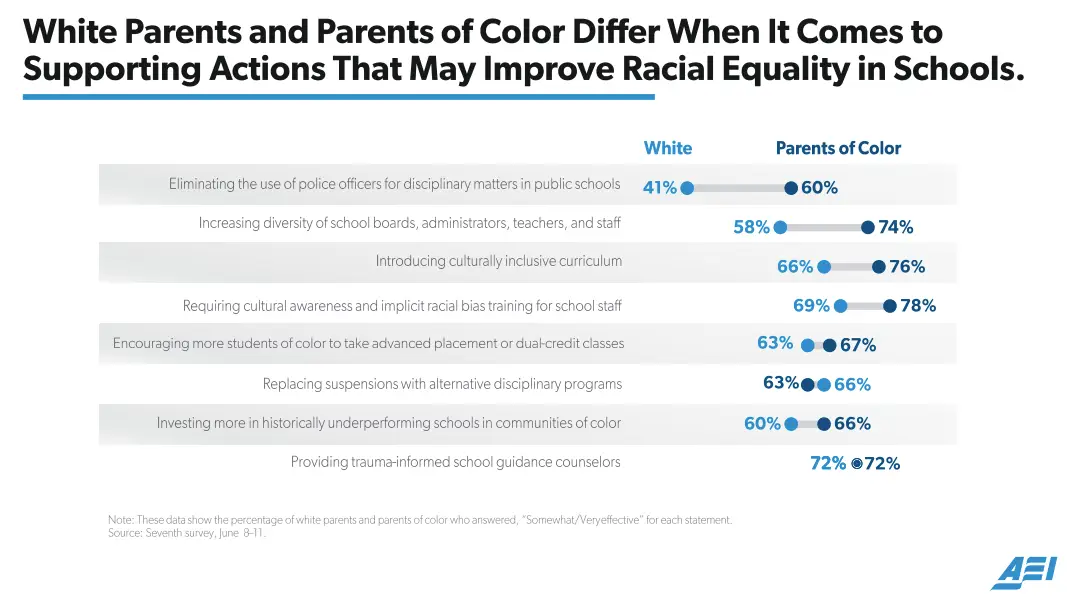

The AEI survey finds that 73 percent of all parents want districts to provide staff professional development that promotes cultural sensitivity and addresses implicit bias, along with hiring “trauma-informed” counselors (72 percent) and developing culturally inclusive curricula (70 percent). These figures vary by parent race, as shown in the chart below.

Source: Coronavirus Family Impact Survey, American Enterprise Institute, June 2020, pg. 42.

With such a strong consensus among parents, it’s surprising that so few districts are responding to the heightened anxiety surrounding race relations. If left unattended, these concerns have significant potential to interfere with learning.

Nonetheless, select school districts are using innovative approaches in the pursuit of racial equity. In North Carolina, for instance, Guilford County Schools is using racially disaggregated data to frame and drive its school reopening decisions. The School District of Philadelphia supports the social-emotional needs of students amid social justice movements through its “Healing Together” initiative, which emphasizes mental health and trauma supports that address racial injustice. Additionally, districts such as Milwaukee Public Schools and Oakland Unified School District have established professional development programs for staff rooted in racial equity practices. Though such efforts are greatly appreciated, prioritizing racial equity remains a concerningly rare occurrence in school districts’ reopening plans.

Parents of children historically underserved by the school districts in whom they place their trust are clearly calling for the injustices exposed by the pandemic to finally be addressed. In the words of Eric Gordon, CEO of Cleveland Metropolitan School District, “Civic unrest caused by the continued senseless deaths of African-Americans across our country further illuminate the huge, decades-long, systemic inequities that communities of color and the school districts that have served them continue to confront.” The key word in this statement is “confront.” Faced with the priorities of parents concerned for the physical, socioemotional, and developmental well-being of their children, districts have a choice: address the systemic inequities presented to them, or continue—as the majority of districts have—to ignore these inequities.

In a recent interview with CRPE staff, Sonja Santelises, CEO of Baltimore City Public Schools, identified “black pain spilling in the streets” as a critical factor school districts must address in order to be successful in serving the entire student population. Santelises says the response to this pain should be threefold: create space for student voice—ultimately shifting conversations between students and leadership, accelerate curricula development to uplift Black and brown voices, and require adults to be accountable—eliminating environments that allow adults to do to children “things that are so obviously discriminatory and inequitable that it is deflating to our students.”

These leaders are showing it’s possible, even necessary, to find new avenues to address historical pain. They are doing so even in the midst of the enormously complex task of reopening schools in a pandemic. District responses to parents whose children experience racial inequity will determine how well our education system serves all of our children.

We know that families of color are already less likely to return to school in-person this fall. Clearly articulating racial equity and a commitment to reviewing policies, curricula, and staff training is important—not only for students’ and families’ safety and validation in school, but also for their eventual return to the physical school community.