This piece was originally published by The 74.

Even as Covid-19 infections continue to fluctuate, roughly one-third of the country’s largest school districts are ending their remote learning programs this fall, according to a new review by the Center on Reinventing Public Education.

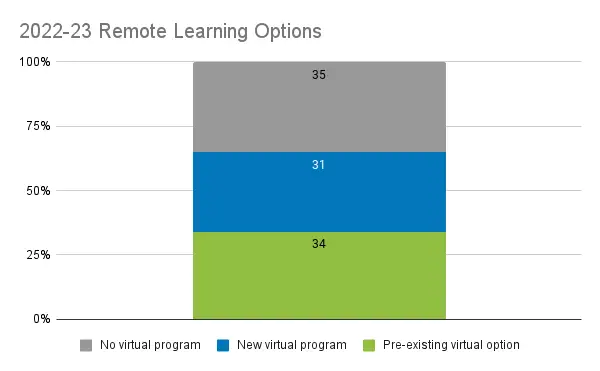

Another third are continuing longstanding programs that had been in place before schools shuttered, and the remaining third are operating new virtual programs created during the pandemic, the review found.

The distinct approaches of America’s 100 largest districts suggest that most are jettisoning remote learning entirely, or reverting back to programs that existed before the pandemic forced them to swiftly provide all families with some sort of online option.

The discontinuation of virtual programs launched during Covid-19 shutdowns could mean they weren’t as effective or popular as those already in place before the pandemic upended America’s education systems in early 2020.

CRPE, a nonprofit research center at Arizona State University, has monitored the learning options offered by the nation’s 100 largest school systems since March 2020. In its review this month of districts’ learning plans for fall, CRPE found 35 indicating they planned to end remote learning entirely, 34 that would continue virtual programs established before the pandemic and 31 that would keep their new, pandemic-era online options.

For example, the Nevada Learning Academy, a virtual school in the Clark County School District in Las Vegas, has operated since 2013. But the temporary distance-learning programs individual Clark County schools initiated last school year are being suspended; Nevada Learning Academy will be the only virtual option the district offers in 2022-23.

In Colorado, Aurora Public Schools plans to continue the virtual school it opened last year for K-8 students, but only for students in third through eighth grades.

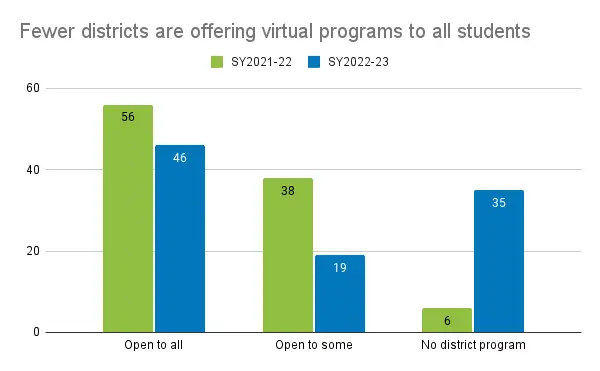

Fewer students in general are eligible to enroll in district-run virtual programs this year than last. In 2021-22, 56% of large and urban districts offered all students the ability to learn remotely. This year, that number dropped to 46%.

In Detroit, the district tightened enrollment eligibility for its virtual school this year to try to improve attendance and reduce failure rates, according to Chalkbeat Detroit. Detroit Public Schools launched the academy in 2021-22, intending to make it permanent, and had planned to spend $5 million on staffing. But it struggled with chronic student absenteeism, and hiring challenges mounted. This year, the school is not accepting students in third through 12th grades who were chronically absent last year and failed one or more core academic classes. The school also did not accept children in kindergarten through second grade who were chronically absent last year, according to the school’s website.

Other large districts have pivoted to expand virtual options — either because students were successful or parents wanted them, or both. Four of the 100 large districts we’ve tracked have widened their virtual academies since the start of the pandemic. Gwinnett County Public Schools in Georgia, for example, recently expanded its full-time online learning option to K-3 students. But parent demand has been strong for Gwinnett County’s online program, which started in 1999. The district even extended the enrollment period for fall 2022 to accommodate the inquiries, according to documents we reviewed.

Last fall, when CRPE reviewed the learning models of large and urban school systems for the 2021-22 school year, 94 of the 100 large districts said they intended to offer remote learning. This year, they have understandably phased out many of these programs as more students return to full-time, in person classes.

What’s curious is that a majority of them are not keeping anything developed in the pandemic, when educators had to innovate quickly to reach all students. Some districts may be ending their programs because they have not matched the academic quality of in-person classes, or because interest dropped among families. But the window is closing for districts to continue pandemic-era innovations that created new options for families. While virtual schooling has become a permanent part of some districts’ repertoire, it’s unlikely to become a defining feature of urban public education in the years to come.