This is the first in a series of updates on our findings on school district response plans. See our latest analysis here.

This week, some school systems across the country returned online after spring break. Others received clearer calls from state leaders to ensure student learning continues through the COVID-19 crisis. A growing number of states—12 as of this writing—have announced students will not return to campuses this year.

These developments helped drive more school districts in our nationwide review to add depth and breadth to their published distance learning plans.

However, the vast majority of those plans still do not require teachers to provide instruction or monitor their students’ academic progress.

This suggests critical building blocks of an effective educational experience are still missing in most places. And the plans detailed in many districts show students and their parents will continue to shoulder a significant responsibility for ensuring learning continues during the crisis.

Our database covers 82 school districts serving approximately 9 million students. We updated the data on those districts and added 18 charter school management organizations (CMOs). We selected CMOs that were part of the Charter School Growth Fund portfolio and served ten or more schools.

More districts have made the jump to providing remote instruction, but they remain a clear minority.

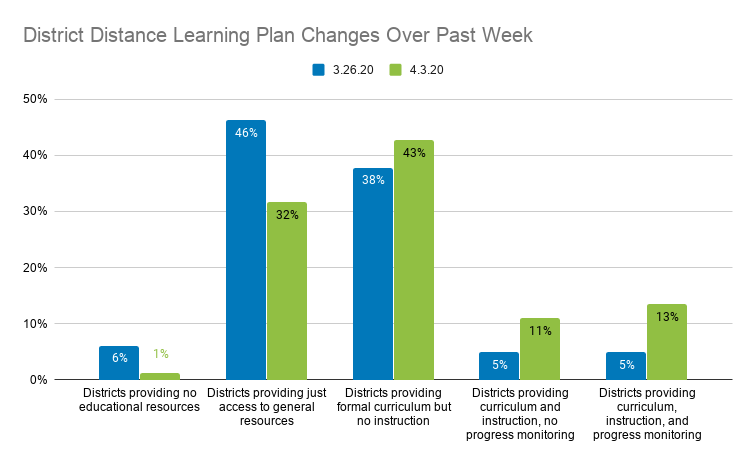

This week, all but one district reviewed either provide a distance learning plan (with formal curriculum, instruction, and/or progress monitoring) or provide access to general education resources, while last week, five districts had no distance learning plan to speak of. And 43% of districts reviewed (excluding CMOs) provide formal curriculum, but no instruction, up from 38% last week.

While still low, the number of districts providing both curriculum and instruction did increase to 11% this week, from 5% last week. And 13% of districts provide curriculum, instruction, and progress monitoring, up from 5% last week.

We also see a significant uptick in districts requiring teachers to review student work or monitor their academic progress. Of the districts we reviewed, 28% require teachers to monitor student progress, up from 7% last week.

While more districts have teachers posting assignments and monitoring student work, most districts reviewed (71%) do not yet require teachers to provide instruction. A majority of districts reviewed (84%) either do not require grading or do not mention it in their plans.

Note: 82 districts reviewed.

As a result, district learning plans rely heavily on parents and students to guide their own work and track their academic progress. These burdens come in addition to the unavoidable demands that the shift to remote learning places on families.

For example, Houston Independent School District rolled out an at-home learning program that provides project-based learning assignments for all students. While the plan calls for teachers to check in with students daily and facilitate courses for middle and high school students, it also relies heavily on students to show initiative and parents to provide support.

The district’s parent resources specifically note students will need parent support to establish and maintain a daily routine that includes check-in calls with teachers, independent work on projects, and teacher-facilitated classes for older school students.

CMOs’ distance learning plans tend to include more progress monitoring and assessment.

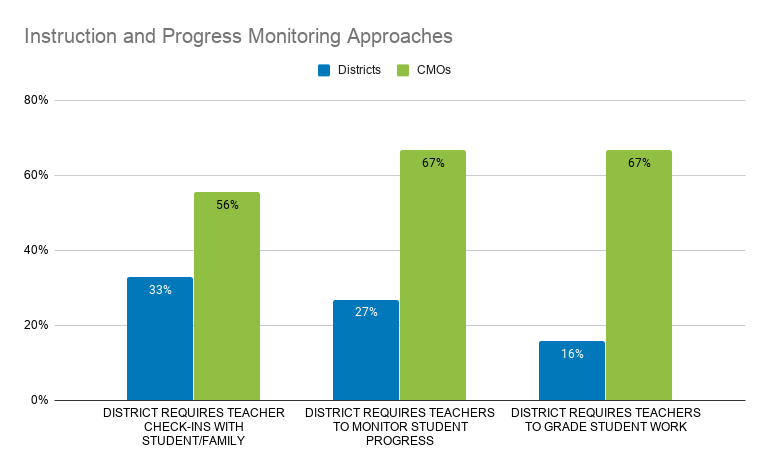

The CMOs and districts we reviewed were not chosen at random, and their numbers are too small to enable broad comparisons between district and charter sectors. However, we do note that the CMOs reviewed appear far more likely than the districts reviewed to monitor student progress, both formally and informally. More CMOs require periodic teacher-student check-ins, monitoring of academic progress, and grading of student work. This is a difference we intend to explore more deeply as we add districts and charter organizations to our database, and explore the practices of individual organizations more deeply.

Note: 82 districts reviewed; 18 CMOs reviewed.

Many districts are gearing up to launch remote learning soon.

Many districts that are not providing remote learning have announced plans to ramp it up in the coming weeks. More districts—40% of those reviewed this week, up from 24% last week—report they have begun training teachers for remote learning.

In Illinois, Gov. J.B. Pritzker extended school closures through at least April 30, and the state Board of Education ordered school districts to transition to “remote learning days.” As a result, Chicago Public Schools, which previously provided only enrichment learning activities, announced distance learning begins April 13—after students return from spring break.

The school district in Chicago gives individual school leaders authority over curriculum, staffing, and budgets. This means the school district could see greater campus-by-campus variation in how distance learning takes shape.

Still, the school district sets some citywide expectations. Schools must make material available digitally, and the district is working to distribute 100,000 new devices to students, but work will also remain available through paper packets.

Teachers will be expected to make themselves available to students for four hours a day, and have been directed to call home and provide weekly feedback. Assignments will be graded, but students won’t be penalized for missed work or poor scores under distance learning. Grades will only count if they improve a student’s score.

More districts have developed plans to support students with disabilities and other special populations.

In previous analyses, we have noted that many districts did not provide detailed plans to support students from special populations. That has started to change.

For example, Minneapolis Public Schools’ new response plan directly addresses how distance learning will work for different student groups. It includes guidance for accommodating IEPs, distributing assistive technology, and measuring progress for students with disabilities during the extended time away from school. The plan outlines specific strategies for supporting English language learners, homeless students, American Indian families, and other vulnerable or marginalized groups.

Some district plans indicate teachers will reach out to families to develop an individualized plan for special learners. Henry County, Ga., expects special education teachers to reach out to families to arrange student accommodations. General education teachers are responsible for meeting accommodations in student 504 plans.

Palm Beach County, Fla., is continuing services for migrant students and classes for English language learners. General education teachers are responsible for accommodating students with disabilities, but special education teachers are available to answer family questions. IEP meetings will continue, over the phone or through digital platforms.

More districts have plans to distribute technology, but it might not be enough to close the digital divide.

The number of districts with technology distribution plans increased to 59% of districts reviewed, up 8% from last week. Nearly half (48%) now have plans to distribute hotpots or help students connect to the internet, up 9% from last week.

However, these growing efforts may not be enough to close the digital divide. Shortages have forced some districts to ration laptops, tablet computers, or mobile hotspots.

For example, Hillsborough County Public Schools in Florida is distributing one device per family—raising questions about how families with multiple school-aged children will manage remote learning. Other districts, such as Anchorage Public Schools in Alaska, prioritize older students in their allocation of devices.

Some schools and districts differentiate instruction by age.

Some districts provide different learning plans for elementary students than for older students. Some districts and CMOs (five of those reviewed) require fewer hours of learning or cover less content for younger students. In general, we find elementary students are being asked to do more reading, physical activity, and self-guided online assignments than direct instruction from their teachers. Activities are more dependent on parent engagement.

Operators may be making this choice due to developmental differences in age, or technology constraints that force them to prioritize online access to older grade levels.

At Dallas Independent School District, elementary school students are directed to access programming on public television or engage in optional self-directed activities from a list of curated resources by grade level. Parents are given sample schedules and routines to put in place and “family fun activities” for free time. Middle and high school students, on the other hand, access required assignments from their teachers through the Google Classroom, Zoom, and PowerSchool platforms.

Similarly, Achievement First, a network of charter schools in the Northeast, focuses on simplicity and literacy for its elementary students. Under its plan, elementary teachers will provide daily one-on-one check-ins with their students, and learning relies upon students’ and their parents’ self-directed use of online programs. By contrast, middle and high school students receive synchronous instruction via Zoom for each class, in addition to using Google Classroom to access additional assignments and instruction. Their progress is monitored and assignments are graded. Teachers are expected to check in with students daily and provide office hours.

Will distance learning ever come close to replacing what students are missing when schools are closed?

Three weeks into our new nationwide educational reality, we do see a steady progression of plans to sustain learning through lengthy school closures.

However, this rate of improvement, and the absolute number of districts providing comprehensive learning anywhere equivalent to what students would otherwise receive if schools were open, remains startlingly low. About three-quarters of districts reviewed are not yet providing consistent access to instruction. An even larger share than that does not require teachers to grade student work.

The charter school organizations we reviewed are more likely to require teacher check-ins with students and measure academic progress, but even this group hovers between just half to two-thirds of those reviewed. It is surprising that more operators aren’t requiring teacher check-ins with students at this time—something we would expect as a basic level of engagement and maintained connection with students.

As we continue to build out this analysis, we will turn our focus to what role states play in influencing or directing the quality of learning, and explore examples of how teachers and students are expanding their roles to make the most of this time. We will also unspool more details from our analysis of charter school management organizations.