We knew the sudden shift to remote learning would be hard. For the last two months CRPE followed a group of large, mostly urban school systems as they clarified their expectations for teaching students, tracking attendance, and monitoring learning. These districts are prominent in the national debate and serve nearly one of every six public school students in the country. But we knew they might not represent the experience of all school systems in the U.S.

Now, for the first time, we are releasing results from a new, nationally representative sample of 477 school systems. This new analysis includes the 81 U.S. school districts in the original database, but adds 396 districts. We apply statistical weights to provide a nationally representative sample of U.S. school districts. For the first time, then, we are able to compare remote education in districts in different types of communities and with different student characteristics.

The original cohort of districts we followed showed increasing clarity and expectations for instruction, tracking student engagement, and progress monitoring. The nationally representative sample reveals a more sobering story.

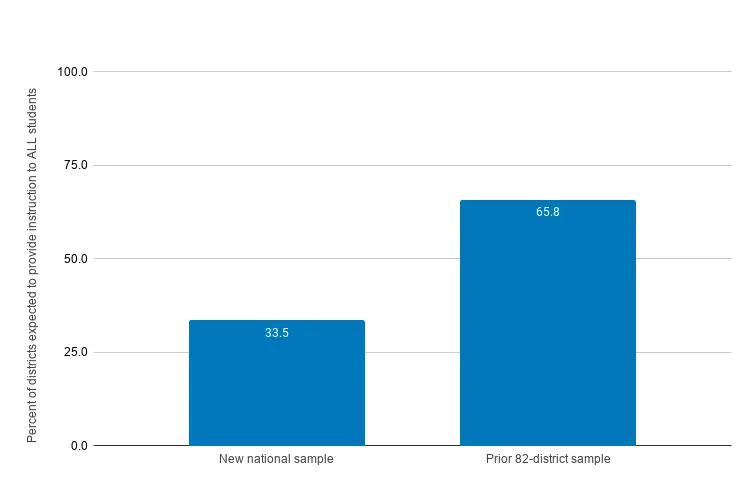

We found just one in three districts expect teachers to provide instruction, track student engagement, or monitor academic progress for all students—fewer districts than our initial study suggested. Far too many districts are leaving learning to chance during the coronavirus closures.

Figure 1. Districts That Expect Teachers to Provide Remote Instruction

We also found significant gaps between rural districts and their urban and suburban counterparts. And school districts in affluent communities are twice as likely as their peers in more economically disadvantaged communities to expect teachers to deliver real-time lessons to groups of students.

These results are likely a function of uncertainty about technology access, but the net result is that many students in these communities were unlikely to receive consistent instruction in spring 2020.

Two-Thirds of Districts Set Low Expectations for Sustaining Instruction

Nationally, nearly all districts—85 percent—made sure their students received some form of grade- and subject- specific curriculum in packets; assignments posted in Google Classroom, Canvas, or some other platform; or guidance to complete segments of online learning software. Educators, however, understand that the instructional core is defined by the interaction between teachers, students, and content. The teachers’ role in this interaction involves more than delivering assignments to students.

Remote instruction can take many forms: live video lessons, recorded lectures, one-on-one support over the phone, or feedback delivered through an online platform. Yet we found that only one-third of districts expect all of their teachers to continue to engage and interact with all of their students around the curriculum content.

We know that some teachers are going beyond their district’s expectations to continue instruction. But lacking clear expectations to provide instruction, districts open themselves up to wide variation in what remote learning looks like from teacher to teacher, subject to subject, class to class.

Experience tells us that low expectations for instruction bode poorly for the students who faced the greatest challenges: those in low-income households, those with disabilities, those who speak a language other than English at home.

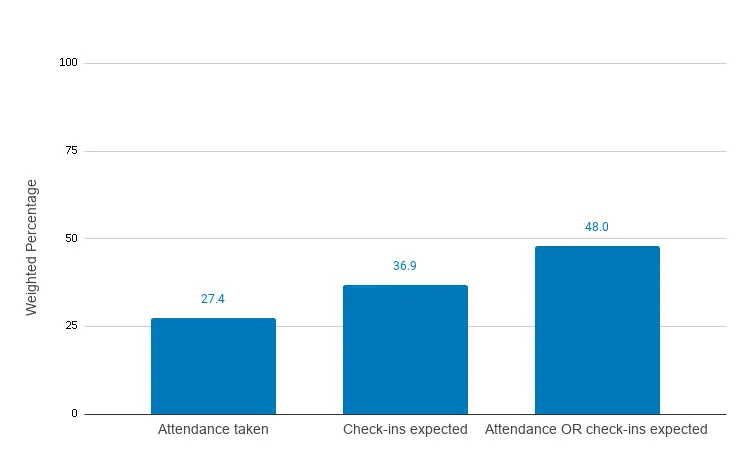

Only Half of Districts Track Students’ Engagement in Learning

Only half of districts nationally expect teachers to track their students’ engagement in learning through either attendance tracking or one-on-one check-ins. Our review finds 27 percent of school districts require schools to track their students’ attendance—which could include monitoring logins to online platforms or other metrics for participation used as a proxy for attendance. This data is one way for districts to monitor which students they are reaching during the pandemic, and to report this information to policymakers and the general public.

Where technology access is limited and students don’t have a consistent method for demonstrating their attendance, tracking regular attendance may not be meaningful. But teachers can still be expected to make regular contact with their students by phone or text to assess engagement and problem-solve for students’ varied experiences at home. We found that a slightly higher proportion (37 percent) of districts require teachers to check in one-on-one with their students on a regular basis. Looking across both approaches to monitor students’ engagement, we found that just under half of districts set clear expectations for monitoring engagement.

Figure 2. Expectations for Tracking Student Engagement

Again, many teachers are keeping in touch with their students—and we know that some are doing so even in districts that don’t require them to do so. But lacking a clear expectation to sustain contact with each student, it isn’t hard to imagine that teachers will stay in touch with students who are easy to contact, while students who are less connected are at greater risk of falling through the cracks.

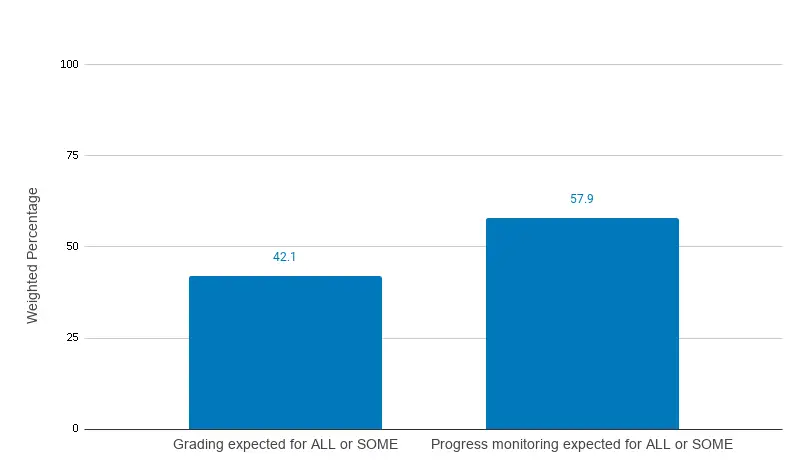

More Than Four Districts in Ten Do Not Require Teachers to Monitor Students’ Academic Progress

Tracking student progress by collecting work for review, assessing students’ progress toward academic benchmarks, or grading their work is the best way to gauge if students are continuing to learn in their remote settings. It may also be our only way to get a sense of gaps in students’ learning that may emerge before the fall, when districts may be able to assess where students stand.

Again, we found worrisome trends in the expectations districts set. Just 42 percent expect teachers to collect student work, grade it, and include it in final course grades for at least some students (typically those in middle and upper grades).

Figure 3. Expectations for Progress Monitoring and Grading

More districts (about 58 percent) expect their teachers to monitor progress or provide feedback (if not grades) for at least some of their students—typically older students. Even still, this means two out of five districts make no firm expectation for students to complete assignments and leave families on their own to keep track of learning. Lacking any progress monitoring this spring, teachers may reconvene with their students this fall with little information on what students accomplished during nearly three months of closures—or what learning gaps emerged, for which students, during months of lost learning time.

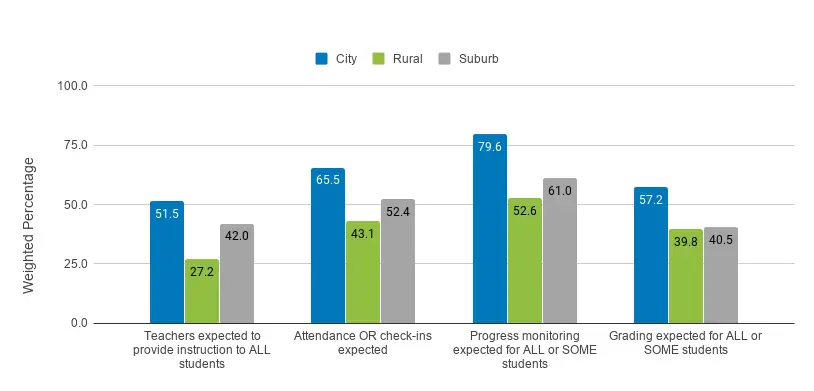

The Largest Divide in Access to Instruction and Progress Monitoring May Be Between Urban and Rural School Districts

Rural districts, where internet infrastructure lags well behind urban and suburban areas, were bound to face more challenges in providing remote learning. Our analysis indeed shows gaps between the expectations for instruction, staying in touch with students, and progress monitoring. Only 27 percent of rural and small-town school districts expect teachers to provide instruction, compared with over half of urban school districts. There are similar gaps for expectations to monitor engagement: 43 percent of rural school districts expect teachers to take attendance or check-in with their students on a regular basis, compared with 65 percent of urban districts. And there is more than a 25 percentage point gap in the proportion of rural districts that require progress monitoring and a 17 percentage point gap in the proportion of rural districts that provide formal grades of some kind, compared with urban districts.

Figure 4. Gaps in Expectations for Instruction and Monitoring Progress by Region

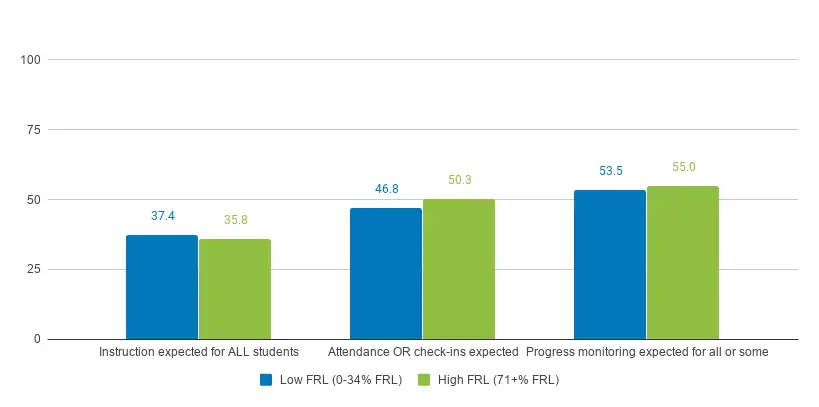

This rural-urban divide in expectations is stark—far more so than the gap in instruction between districts with high concentrations of students who qualify for free or reduced-price lunch. When we divide the sample into quartiles based on the district’s concentration of economically disadvantaged students, we do not see a clear divide between the districts with the highest and lowest quartiles in terms of expectations for instruction, tracking student engagement, or progress monitoring.

Figure 5. Expectations for Instruction and Monitoring by High and Low Free and Reduced-Price Lunch Districts

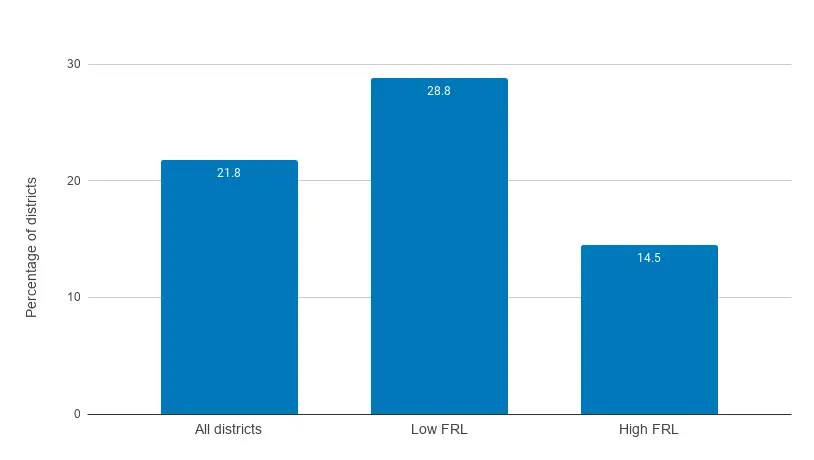

Affluent Districts Are Twice as Likely as High-Poverty Districts to Require Live Instruction

More affluent school districts are more likely to require live video instruction from teachers. While expectations around synchronous, or real-time, teaching are uncommon across the board (expected in 21.8 percent of districts), only 14.5 percent of school districts with the highest concentration of students receiving free or reduced-price lunch expect teachers to provide live instruction. The most affluent 25 percent of districts in our sample are twice as likely to expect real-time teaching.

Figure 6. Districts Expect Teachers to Provide Synchronous Instruction to At Least Some Students

This gap is most likely due to concerns about students’ access to technology in high-poverty districts but does show how concerns about access can shape the learning opportunities districts expect their teachers to provide—with the net result that higher-poverty districts are setting somewhat lower expectations that students receive live interaction with teachers and classmates.

Looking Ahead to Summer and Fall

Rolling out quality remote learning plans is something that would ordinarily take districts months, if not years, of planning. The COVID-19 crisis forced districts to accomplish this in a matter of weeks, while balancing equity and connectivity needs and providing access to basic resources. It was unlikely to be perfect.

This spring, it seems far too many school districts let perfect be the enemy of good. In the challenge to connect all students, they left the level of instruction and progress monitoring up to the discretion of schools and teachers, thus creating highly varied learning experiences for their students. Without clear expectations across the board, and therefore pressure to meet the needs of each student, many districts likely left at risk the learning experiences of students who face the greatest challenges.

This need to pick up the slack was felt by parents who, in surveys, reported worry that their child is missing instruction and felt unsure about their ability to support their child’s learning at home. In one survey only 33 percent of parents reported regular access to their child’s teachers. And teachers felt these low expectations, too: in another survey, over half of responding teachers were worried that their students would fall behind academically. Most report less time spent on instruction than usual, and lower engagement from their students.

Districts have an opportunity to do better by students, teachers, and parents this fall. Official guidance advises schools to prepare for continued uncertainty and some level of remote learning for fall 2020. School districts now have several months to plan ahead to align the resources, create teacher professional development, and assess community priorities to design plans for the fall that have high expectations for each student’s learning and are responsive to each student’s needs. CRPE will support this hard work by continuing to track districts’ plans for summer and fall learning, sharing innovative strategies, and pushing for ways funders and policymakers can alleviate the burden. Despite the challenge of the COVID-19 crisis, we cannot continue to leave learning to chance for any student.

Download the full brief to see the data tables and our methodology.