Today the Center on Reinventing Public Education is releasing three briefs that shed light on the debate surrounding charter schools in California.

In short, they conclude:

- Charter schools are not a major driver of recent enrollment declines in California’s school districts.

- There is no evidence that charter schools are to blame for school districts entering states of fiscal distress.

- Charter schools have, according to available evidence, important benefits for California communities and limited costs to the state.

There is no question California’s public schools face financial challenges. The cost of meeting the diverse needs of students—those who are learning English, those affected by trauma, and those in need of special education services—is rising faster than the state’s support for them. Teacher pension costs doubled between 2013 and 2017. Districts struggle to meet teachers’ demands for salary increases, while many teachers struggle to afford homes in the cities where they work.

Amid this backdrop, a growing number of critics in California and nationwide have argued charter school growth undermines school district finances and forces cuts in the quality of schooling districts can provide. These claims have recently gained momentum. In 2019 teachers unions made stopping charter school growth part of their collective bargaining agendas. As part of a settlement with the United Teachers of Los Angeles, the local school board released a statement in support of a temporary moratorium on charter school growth. The State Superintendent of Schools has convened a task force to consider charter costs and the impact on school districts. The Legislature is now considering various bills on charter school policy—including one that would impose a statewide cap.

Costs and Benefits

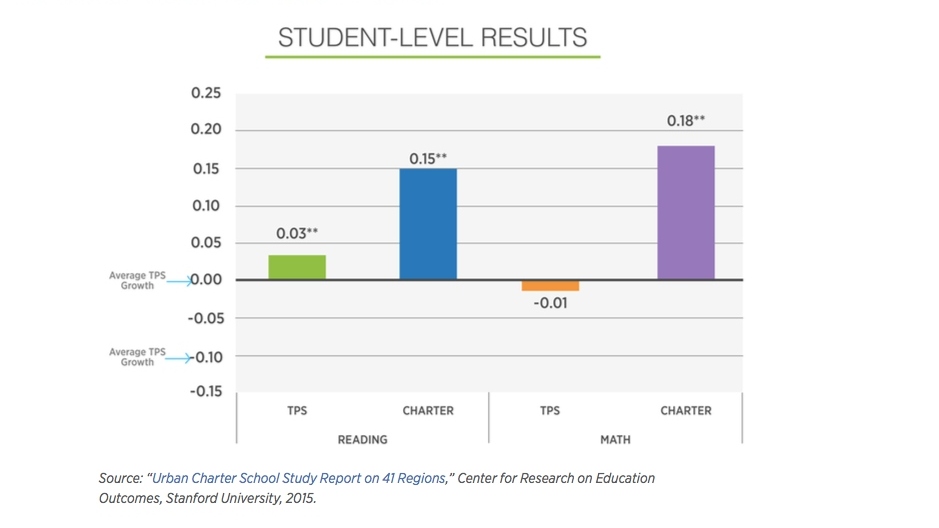

Halting charter schools would come at a cost because charter schools also provide benefits to the communities they serve. Some of those benefits, like giving families more schooling options, are hard to quantify. Others, like charter schools’ positive effects on student achievement, have been quantified by studies that control for student demographics. According to Stanford University’s Center for Research on Education Outcomes, charter school students improve more quickly in reading and math—especially in Southern California and the San Francisco Bay Area, and particularly among black students, Hispanic students, and students living in poverty.

FIGURE 1. Average Academic Growth for Charter School Students Relative to Performance of Virtual Twins in Traditional Public Schools in the Bay Area – All Students

California policymakers should also pay attention to other effects charter schools may have on student learning, such as their effect on college enrollment and graduates’ earnings. These have not been rigorously studied in California, though they have in some other states.

From a state policy perspective, decreased revenues to school districts should be considered interagency transfers, not costs to the state. Other potential costs, such as any differential costs for serving students with special needs, should be addressed in state funding formulas.

Our analysis recognizes that school districts have real pain points when they must adjust to declining revenues, whether or not charter schools are the cause. However, we recommend state policymakers look to solutions such as transition aid and other supports to help districts and charter schools thrive together.

Charter Schools’ Impact on District Enrollment

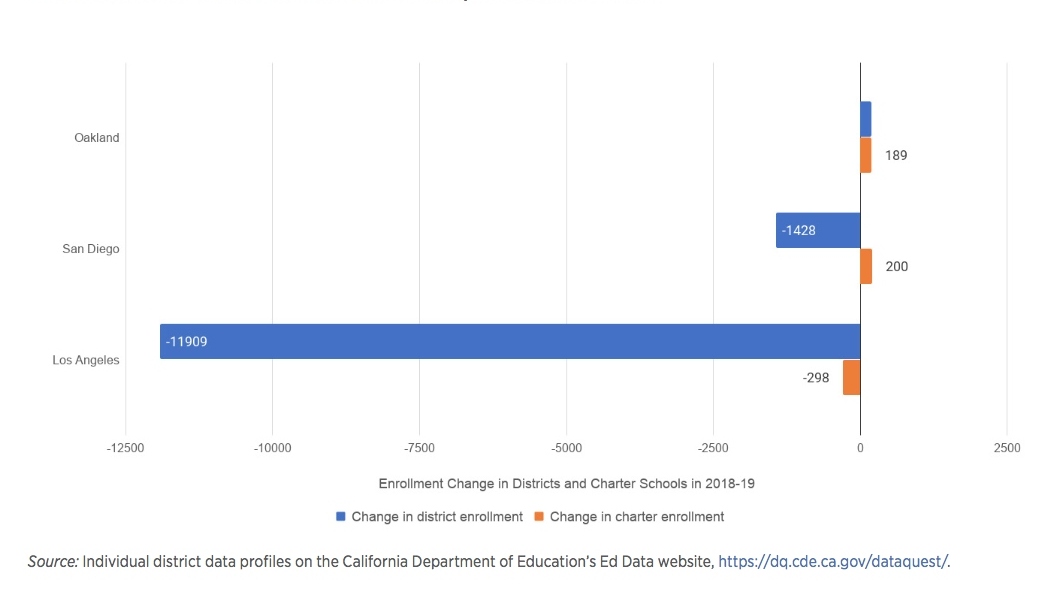

When school districts lose students, they lose revenue. It can be difficult for them to adjust. However, our analysis of district enrollment loss shows charter schools are just one of the factors driving enrollment declines in California’s school districts.

Indeed, in the most recent school year (2018–2019) charter school enrollment growth can account for little or none of the enrollment loss experienced by Los Angeles Unified and San Diego Unified school districts. In Oakland, the district gained more students than charter schools did.

FIGURE 2. Enrollment Continues to Decline in Los Angeles Despite Slowed Charter School Enrollment Growth

For many school districts, charter schools are not an influential contributor to enrollment loss simply because there are no charter schools nearby for students to enroll in. Only a minority of California school districts (15.8 percent between 1998 and 2015) have any charter schools.

Furthermore, not every student who enrolls in a charter school leaves a district school. In Oakland, an average of approximately 15 percent of charter enrollees come from parochial or private schools.

Causes of Fiscal Distress

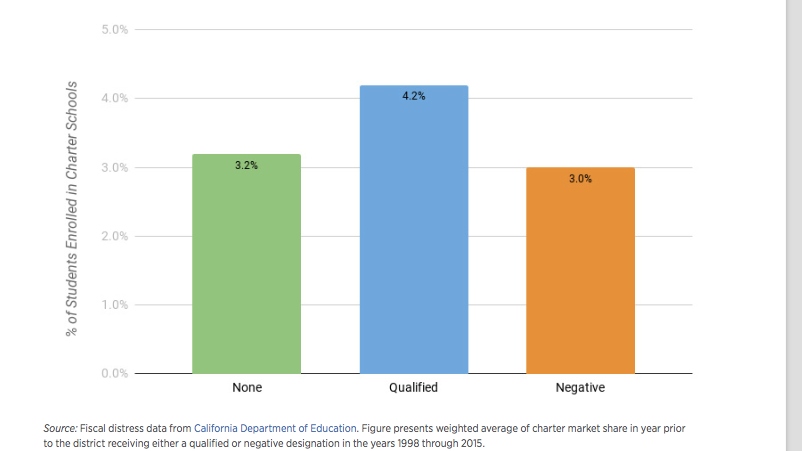

It’s no surprise, then, that there is no evidence charter schools cause financial distress in school districts. California school districts that faced fiscal distress have, on average, lower shares of students enrolled in charter schools.

FIGURE 3. School Districts Entering Fiscal Distress on Average Enroll Smaller Shares of Charter School Students

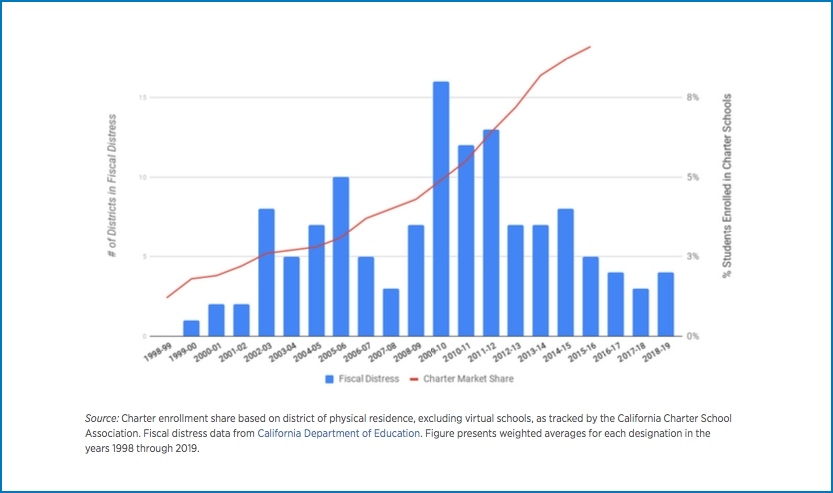

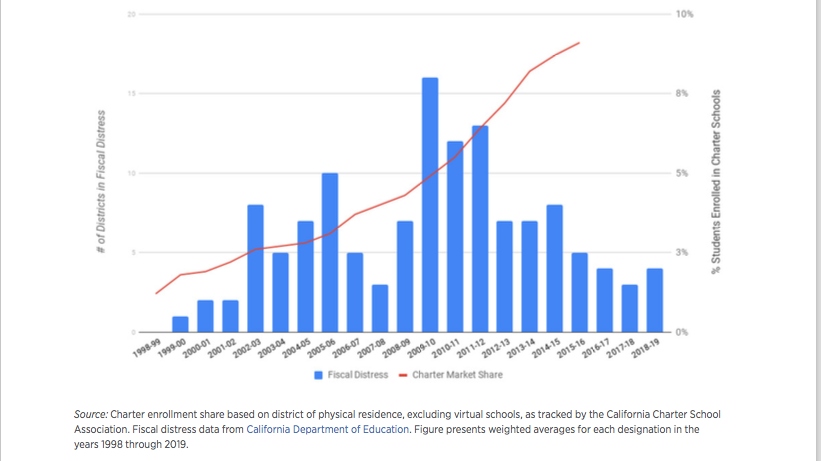

School districts that enter fiscal distress are often able to fix the situation. The percentage of California school districts flagged by the state for troubled finances peaked in the years after the Great Recession, but the situation improved as the economy recovered—a period when charter schools kept growing.

FIGURE 4. Few California School Districts Face Fiscal Distress Despite Growing Charter School Enrollments

In more recent years, however, the economy has continued to grow, charter school growth has stalled in many regions of the state, and fiscal challenges are mounting for some California school districts. Teacher strikes in Los Angeles brought the district’s budget strain into the spotlight. Sacramento is poised for a high-profile state takeover. Oakland’s superintendent is calling for the state to increase its commitment to public school students.

Rising to the Challenge

These problems can affect all public schools, including charter schools. Preventing more students from choosing charter schools will not fix them. School districts, charter schools, and state policymakers must work together on changes that will.

We offer some potential starting points:

- The state should work with school districts to develop more accurate budget and enrollment projections. This will help restore trust with taxpayers and teachers negotiating salaries, and prompt a more honest conversation with taxpayers and state policymakers about public schools’ funding needs.

- Policymakers should consider transition aid for districts where students leave for charter schools, as states like Massachusetts have done. This could help districts deal with costs they can’t easily shed, and compete more effectively to attract students.

- In districts struggling with the effects of persistent enrollment declines, charter schools and the state might pay into debt reduction funds that a district could tap if it made strides reducing costs and increasing financial transparency. Charter schools, in return, could receive improved access to district facilities.

These policies will not solve the complex challenges facing California’s public education system on their own. But they will help set the table for an honest public debate about what that will require.