Generative AI has led to a seismic shift in the U.S., with major implications for the present and future states of our societal systems and institutions.

While these advancements could contribute to major learning gains in the classroom, they have also generated a great deal of uncertainty as educators, parents, and students grapple with the promise and potential peril of GenAI. We know that GenAI is already reaching into all aspects of society, including work, media, medicine, and entertainment. But education is an area where GenAI could have even more profound effects.

Teachers are caught in a very difficult place on GenAI issues. Very few teachers have likely received any training on the topic, and what they know is therefore highly variable. Fewer than 20% of teachers are using GenAI at all, perhaps because few states or districts have provided clear policies about how to handle GenAI.

A brief anecdote provides a snapshot of teachers’ current challenges with GenAI in their classrooms. When one of the authors of this blog attended “meet-the-teacher” night for a high schooler, another parent asked the AP English teacher,“What is your policy on AI so that we can be consistent at home?” The teacher answered candidly, “I don’t know! I go back and forth!” He explained that when used meaningfully, AI has the potential to teach children how to be critical thinkers and better writers. For example, students could be asked to upload a paragraph and prompt for how to improve the paragraph, along with explanations behind each of those improvements. But, he emphasized, this is not how they are using it now. They are much more likely to prompt, “write me a two-page essay on the Grapes of Wrath, use quotes, and cite page numbers.”

But as the anecdote above exemplifies, parents are also at the front lines of supporting students with application of GenAI in education, and we have very little information about what parents know, understand, or think about AI or its potential uses in schools. To address this gap, we surveyed a probability-based sample of over 1,800 American households about these issues during the summer of 2024 as part of the Understanding America Study. Based on the results, we reach four main conclusions about parents’¹ current awareness of and beliefs about GenAI issues in schools:

- Schools and teachers aren’t communicating with parents about GenAI.

- Parents mostly either don’t know whether their children are using GenAI or think their children are not using it.

- Parents have mixed and hesitant views about the potential role of GenAI in education.

- There are gaps between more and less educated parents in their views on GenAI, with more educated parents generally more supportive.

Vacuum of Communication

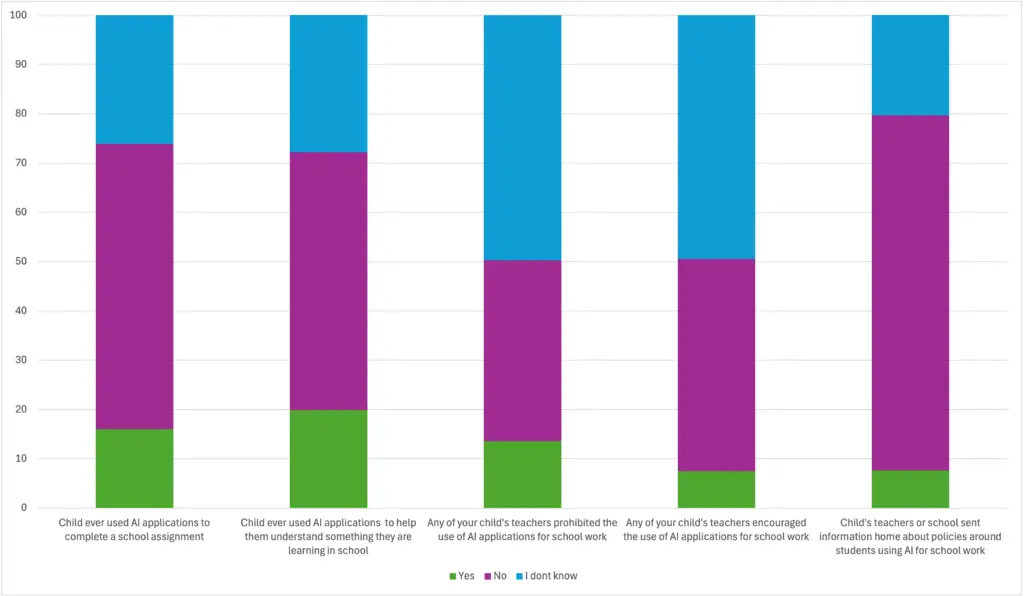

First, schools don’t seem to be communicating much of anything to parents about GenAI issues (in line with our own experiences!). Nearly three quarters of respondents (see Figure 1) said their children’s teachers or school had not sent home information about policies related to student use of GenAI, and half reported not knowing whether their children’s teachers were prohibiting or encouraging the use of GenAI. Communication was slightly higher for secondary parents (10%) than for elementary parents (4%), but there is vanishingly little school-to-parent communication about these issues. Schools are missing an important opportunity to work with parents by not informing them about GenAI issues and policies.

Figure 1: Parents’ overall awareness of AI issues

In the Dark

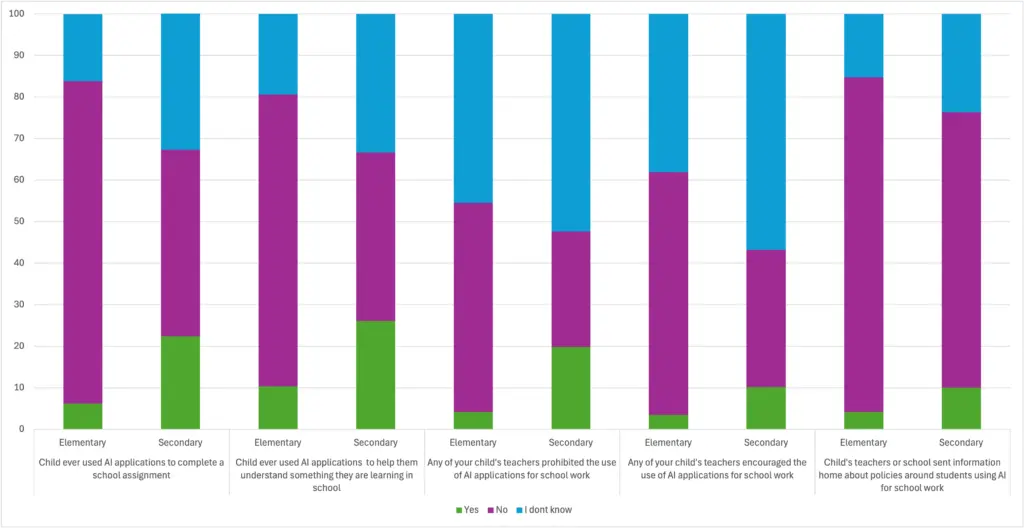

Second, as a result, parents are mostly in the dark about GenAI in schools and are not talking to their children about the issue. By and large, parents do not believe their children are using GenAI much. As shown in Figure 1, just 16-20% of parents believe their children use GenAI for education-related purposes (versus 52-58% who say no, and 26-28% who don’t know). As shown in Figure 2, Parent reports of children’s use is certainly higher for secondary school students (22-26%) than for elementary students (6-10%), but this is still far from widespread use. Similarly, only 14% of parents say they’ve discussed appropriate uses of GenAI with their children (7% for elementary-aged children, 21% for secondary-aged children). We will have similar survey data collected from teenagers who participated in the Understanding America Study soon, and it will be interesting to see how parents’ reports match what teens tell us.

Figure 2: Parents’ awareness of AI issues, separately for parents of elementary and secondary students

Ambivalence and Uncertainty

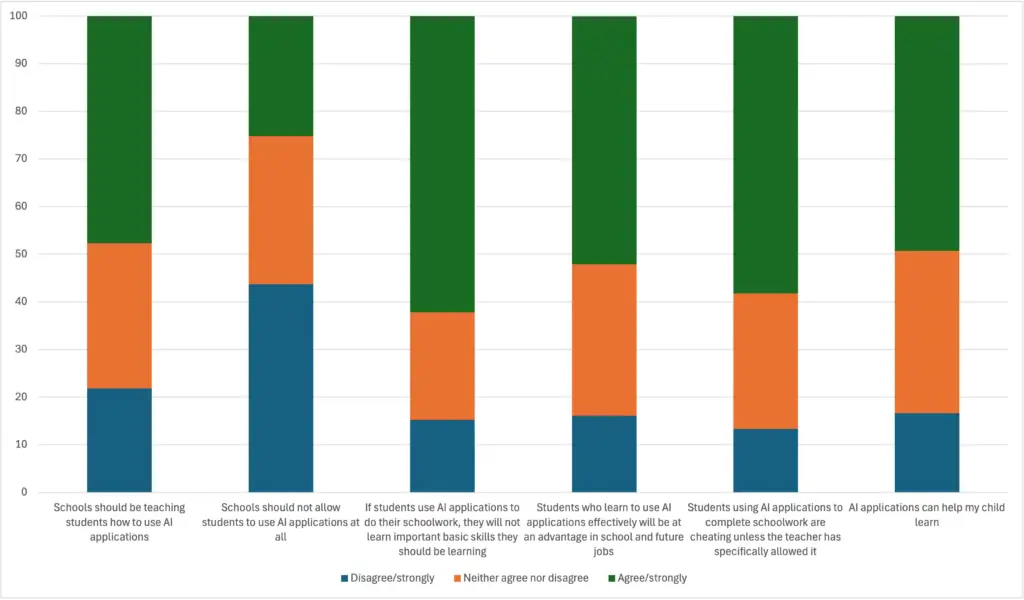

Third, perhaps reflecting their own lack of knowledge about GenAI issues, parents express ambivalence and uncertainty about the uses and potential impact of GenAI. As shown in Figure 3, parents were quite split on most of the opinion questions we asked. For instance, 58% agreed that students using GenAI to complete schoolwork was cheating unless explicitly approved by the teacher, but just 25% said schools should not allow students to use GenAI at all. And 48% said schools should be teaching students how to use GenAI (with 49% saying GenAI can help their children learn), but 62% said students using GenAI will not learn important basic skills they should be learning. On most of these items, about a third of respondents neither agreed nor disagreed—a high degree of uncertainty. This level of uncertainty around whether GenAI is cheating can also blur the lines about ethical use of GenAI for kids.

Figure 3: Parents’ opinions about AI issues in schools

Gaps in AI Attitudes Based on Parent Education Levels

Fourth, there are some sharp gaps between more and less educated parents in attitudes about AI. As shown in Figure 4, more educated parents are overall much more likely to express opinions supportive of the potential of AI than less educated ones. For instance, 62% of parents with a BA or more say schools should be teaching children how to use AI, versus just 31% of parents with a high school degree or less. There are similarly large gaps on views about AI use offering an advantage in school and future jobs (68% agree for BA-holding parents, 35% for high-school-only) and that AI can help children learn (62% agree for BA-holding parents, 36% for high-school-only). It is important to note that some of the differences between groups are likely due to gaps in knowledge about the various ways GenAI can be used beyond students prompting for direct answers or plagiarizing (less educated parents were consistently more likely to express neutral opinions about these issues).

Figure 4: Parents’ opinions about AI issues in schools, separately by parents’ education level

A second round of questions to the same households is planned for early 2025. We will examine if parent familiarity and knowledge is changing, and if changing knowledge or familiarity may be changing parent attitudes. We will also examine whether there has been any increase in school- or teacher-based communications since our last round of questioning in summer 2024.

The introduction of powerful new AI models represents both a threat to and an opportunity for our education systems. While we and others see potential promise for using these tools in ways that support teachers and improve the processes by which students learn, this will only happen if administrators and policymakers make smart decisions. Addressing the four challenges highlighted in our survey is a great place to start.

¹ Approximately 70% of respondents are the household child’s parent. Another 20% identified as the child’s grandparent. The remainder included adult siblings, aunts/uncles, and non-family caretakers. We use the term “parents” for simplicity.

This blog is the first a series where CRPE invites thought leaders, educators, researchers, and innovators to explore the transformative potential—and complex challenges—of AI in education. From personalized learning platforms to AI-powered administrative tools, the education landscape is evolving rapidly. Yet, alongside opportunities for increased equity, efficiency, and engagement come pressing questions about ethics, accessibility, and the human element in learning environments. Join us as we unpack the promise, the pitfalls, and the path forward for AI in schools.

To learn more about CRPE’s latest work in AI, visit our AI in Education research page. To stay up to date on all things education and AI, including our newest releases, subscribe to Robin Lake’s newsletter, Think Forward: Learning with AI.