More states are acknowledging the implications of artificial intelligence technology for our society and institutions, particularly our school systems. However, the emerging state-level guidance for districts is broad and avoids regulatory language, according to CRPE’s latest review of state education department actions on AI. While generative AI rapidly advances, many states continue to defer to districts to decide what to do in their schools.

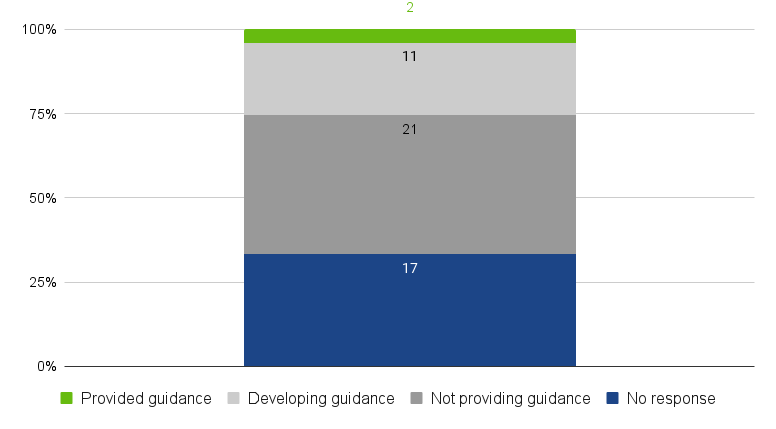

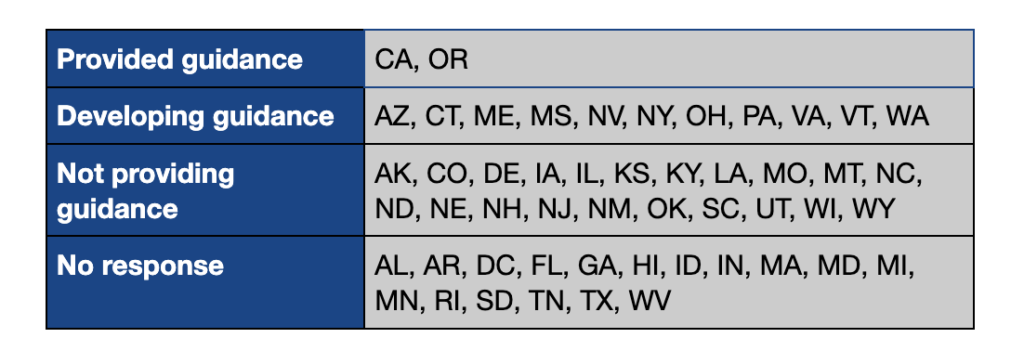

CRPE reached out to all 51 State Departments of Education, requesting updates on their approach to AI guidance. Just two states—California and Oregon—have offered official guidance to school districts on using AI in schools this fall. Another 11 states are in the process of developing guidance, and the other 21 states who have provided details on their approach do not plan to provide guidance on AI for the foreseeable future. The remaining states—17, or one-third—did not respond to CRPE’s requests for information and do not have official guidance publicly available.

That any guidance is published or in the works for 13 states is a significant development since August, when CRPE’s national scan found that no states or territories had released official communication to help schools navigate the use of AI in teaching and learning. But our deeper review of state department responses indicates that the majority of states still do not plan to shape AI-specific strategies or guidance for schools in the 2023-24 school year.

State Department of Education approaches to AI guidance, September 2023

Early state guidance examines appropriate uses of AI, AI evaluation, and best practices

Guidances that have been published or that are currently in development focus on the ethical and equity implications of AI’s use, recommendations for teachers’ and students’ appropriate use of AI, and emerging best practices to enhance instruction, according to documents reviewed by CRPE. The guidance also explores the potential for AI to improve systemic inequities. However, it does not go so far as to provide regulatory guidance.

Oregon’s guide, Generative Artificial Intelligence (AI) in K-12 Classrooms, emphasizes the potential equity implications of using AI in the classroom, and provides a table of strategies to address potential impacts. It also outlines data privacy implications, describes the potential for using generative AI to support students and teachers, and suggests policy considerations for districts.

California’s Artificial Intelligence: Learning with AI Learning about AI document also names equity and bias issues but additionally articulates how AI could help bridge equity and diversity workforce gaps in STEM fields. “By integrating AI education with a focus on diversity and inclusion, we can pave the way for a more equitable future in these disciplines,” the guidance says. It provides recommendations for districts’ evaluation of AI systems and encourages districts to integrate AI concepts and computer science standards into schools’ curriculum.

The 11 other education departments with guidance in progress either plan to provide official guidance later, are providing informal guidance, or have been mandated to develop guidance. The Maine Department of Education plans to release guidance in October 2023. Connecticut’s State Department of Education will first engage stakeholders including teacher unions, superintendent groups, and school leaders to discuss policies that may be needed.

Most states are cautious to influence AI decisions at school, district levels

The remaining 21 state departments that do not have plans to develop AI guidance express different rationales, and many respondents cede responsibility to districts as the ultimate decision-makers on AI policy and approaches. Montana, Iowa, North Dakota, and Wyoming defer to districts and/or reference local accountability policies in lieu of providing guidance. In contrast, North Carolina and Vermont acknowledge districts’ decision-making power, but are still developing guidance to inform their actions. Vermont is surveying its school districts and urges administrators to “evaluate AI use in their respective schools and create policies to direct its use as deemed needed.”

Some departments are aligning their stance with other state actors. The Illinois State Board of Education has not yet issued official guidance on AI, but its general assembly and governor recently passed Public Act 103-0451 which will launch a Generative AI and Natural Language Processing task force to study and report back on the use of AI. The Colorado Department of Education and Montana Office of Public Instruction shared that they will only administer guidance after receiving direction via new legislation or direction from the state board.

Other departments share that they have no plans to explore this topic in the foreseeable future. The Kansas State Department of Education, for example, “has not issued any guidance to districts regarding AI technology and, as of right now, has not discussed any plans to do so.”

Finally, some states are opting to provide resources or technical support, but stop short of providing guidance. Six departments reference the U.S Department of Education’s May 2023 report on Artificial Intelligence and the Future of Learning, and others are providing resources or partnerships with organizations like the International Society for Technology in Education (ISTE), Code.org, and TeachAI. The North Carolina’s Department of Public Instruction (NCDPI) hosted a summer teacher conference that included sessions on effectively and safely using AI, and it will offer ongoing professional learning and resources.

With or without providing guidance, states acknowledge AI’s potential

States that provided us with their stance on AI do recognize that AI is here to stay. Most balance the opportunities inherent in technology and AI with the risks that misuse could bring. The Oregon Department of Education explains: “While digital learning and education technology has the potential to address inequities when implemented with an equity focus and mindset, in the absence of this intention, digital learning and education technology can also exacerbate existing inequities [for marginalized students].”

Several mid-Atlantic states are designing plans to grow their local AI workforces. The North Carolina Department of Public Instruction states that “given that AI tools are increasingly prevalent in their future professional environments, empowering students to familiarize themselves with these technologies is essential,” and supported the passage of a house bill that requires all North Carolina high school students to complete a computer science course upon graduation.

In neighboring Virginia, the governor issued an executive order in September for its Department of Education to develop workforce plans to prepare students for future careers in AI. Nearby Maryland’s state leadership also aims to drive new investments in AI technology.

California’s official guidance language charges that as students master AI, they will be able to master larger societal challenges. “As we incorporate AI education in K-12 schools in a way that provides opportunity for students to not only understand AI but to actively engage with it, we demystify AI, promote critical thinking, and instill motivation to design AI systems that tackle meaningful problems.”

In this moment, states have a responsibility to lead—and lead quickly

This second review of state actions toward AI demonstrates that more states are acknowledging that AI will effect schools and districts, as well as the lives of teachers, students, and families. 13 states have produced or are producing some kind of guidance to help districts grapple with those implications. But 21 states have not entered the conversation yet. This means students and teachers in those states may be subject to more reactive, divergent, and potentially inequitable impacts, all while generative AI continues to advance at a remarkable pace, hastening and expanding its potential to transform education. And, district leaders are asking for more help: CRPE’s recent focus groups with school and district administrators found that they would like more state guidance on using generative AI ethically and responsibly.

Federal guidance is lagging. The Biden administration’s executive order on AI, released on October 30, directs the federal Department of Education to develop resources, policies and guidance that address AI in education—but not for another year. At best, the Department of Education will release an “AI toolkit” sometime this spring. This means that many schools will have to feel their own way in the dark around effective AI practices for the 2023-24 school year, outside of any local efforts to step up.

States must use this moment to steward collective action and encourage responsible decisions. They possess a unique power—to convene and drive coherence across schools—and this role is especially critical now. Recommendations for generative AI guidelines in education and organizational adoption strategies abound, and TeachAI recently released their Guidance for Schools Toolkit, which provides more in-depth guidance than any state-produced materials to date. States could consider taking Japan’s approach: their education ministry created provisional guidance, is studying its implementation in select districts and schools, and amending it as needed. Waiting for more information or for other agencies to weigh in increases the likelihood that AI’s implementation in schools will be uneven, inequitable, and ineffective. The longer that states wait to provide guidance, the more ground they’ll have to cover when they do—and AI isn’t waiting for anyone.