Seattle Public Schools made local headlines for its decision to award only As or incompletes as part of its revised grading policy during COVID-19 closures. Seattle district leaders say their policy “intentionally minimizes harm for students furthest away from educational justice” during the current crisis, but it may overlook harm caused over the longer term from lost learning. Looking toward an uncertain fall, school systems must plan a better way.

Nationwide debates rage over similar policies as districts contend with a conundrum: recent research suggests that rigorous grading supports student learning, but students are working from vastly different remote learning contexts that might make it difficult, if not impossible, for all students to meet teachers’ expectations. Millions of families are out of work and many parents and guardians are juggling the roles of caregiver, teacher, and employee while dealing with stress and grief. Some students may not have a laptop to work on, a working internet connection, or a quiet place to study. Others may have problems in their lives—like food or housing insecurity fueled by the economic slowdown—that make learning at home even more difficult.

But while taking a more forgiving stance on grading now might alleviate stress for some students and administrators, months of uneven expectations for student learning could create more inequitable outcomes in the long run. Students with ample resources at home could boost their learning, while those with fewer could fall further behind. Many are worried about closures creating an extended “summer slide.”

Navigating this tension presents a difficult task for school system leaders. They have to guess the “right” policy for grading and expectations for students, often with minimal guidance from state agencies.

The Spectrum of Grading Policies

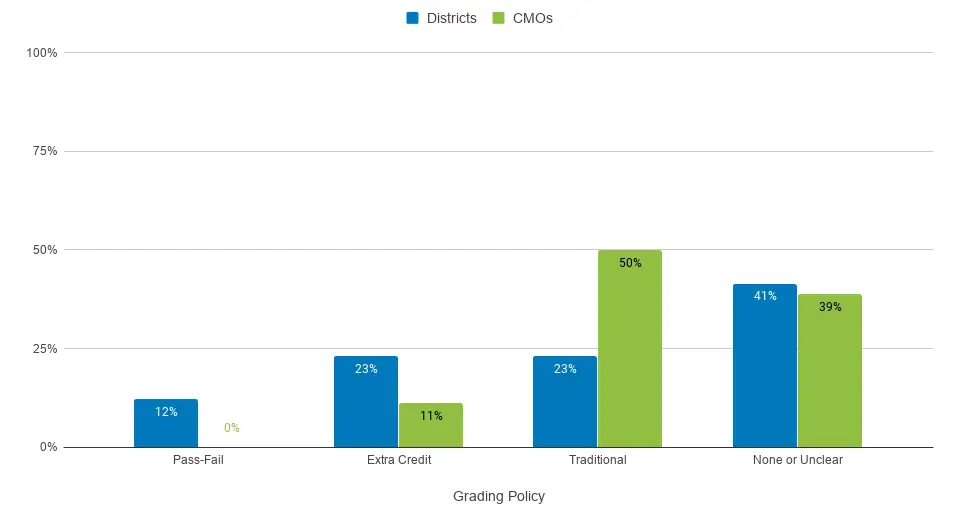

In our database of 82 districts and 18 of the largest CMOs, school systems generally fit into one of four policies: traditional grading (A-F scale); pass/fail or pass/incomplete; “extra credit,” where grades are essentially paused from third quarter and work assigned during closure can only increase student grades; or no grading (or the policy was unclear).

As of our review on April 23rd, we find that 41 percent of school districts are not grading during this spring. Of those that are grading, an even split occurs between the “extra credit” policy and traditional grading (23 percent for each). Half of the charter networks are using a traditional approach to grading, and a smaller proportion (39 percent) are assigning no grades or have an unclear policy.

Looking more closely, we found districts with all types of policies grading with a sense of grace for current student experiences, or with a “do no harm” philosophy. Though NYCDOE is using a traditional grading scale, they ask teachers to grade with an understanding of student circumstances, and are allowing students to make up work from failing grades through the summer and fall. School districts like Long Beach Unified School District and Seattle Public Schools cite “do no harm” as the philosophy behind pass/incomplete. Chicago Public Schools reference similar ideas behind their “extra credit” policy, while Detroit and Oklahoma City use similar reasoning behind issuing no grades at all during this time. With such a range of approaches tied to “do no harm,” how can school systems ensure that their policy is in fact “doing no harm” by supporting students over the longer term?

Looking Toward the Fall

These grading policies took shape in a rapidly evolving situation as school systems attempt to balance many demands—all within a short, uncertain time frame. But what does a “do no harm” policy look like as school systems plan for fall?

School systems must meaningfully assess student work. They should take this opportunity to design systems that accomodate students in the most challenging circumstances while supporting high expectations and real learning. Policies that make assignments optional or “extra credit” are not likely to help students in the long run. But grading policies don’t have to look the same as they always have, and can include special exemptions for students facing the greatest hardships as a result of the pandemic and economic downturn.

What would it take to ensure students most marginalized by COVID-19 can engage successfully with their schoolwork, so that expectations and grading policies are equitable?

School districts could engage with families to understand the various supports needed to access instruction and complete assignments. This may include internet connections, devices, one-on-one support from teachers, and clear guidance for parents, but also mental health and other social supports for students and families. School districts may not be able or best positioned to directly provide each of these, but should coordinate closely with parent groups, nonprofits, other agencies, and telecom providers to ensure all students have what they need.

But even the best support systems might not be enough to manage the wide range of student needs that schools will face in the fall. School systems may want to use this time of upheaval to consider innovative ways to track student progress, give feedback on student work, and refocus on deeper learning and mastery. Could anything gleaned from how students responded to the shifting expectations during school closures be brought into the fall? What can we learn from schools and systems that already use more flexible approaches— like mastery-based learning, or Montessori models that may eschew traditional letter grades or provide more individualized strategies? CRPE will be on the lookout for innovative practices here.

“Do no harm” is an appropriate philosophy in times of crisis, and should always be a baseline for how school systems make choices. But school system leaders must balance the short-term harm of unfairly penalizing some students against the long-term harm of low expectations.

As they prepare for fall, school systems must build resources and partnerships that will ensure all their students can participate in school and focus on learning. That way, they can confidently adopt grading policies that expect all students will continue learning amid this crisis.